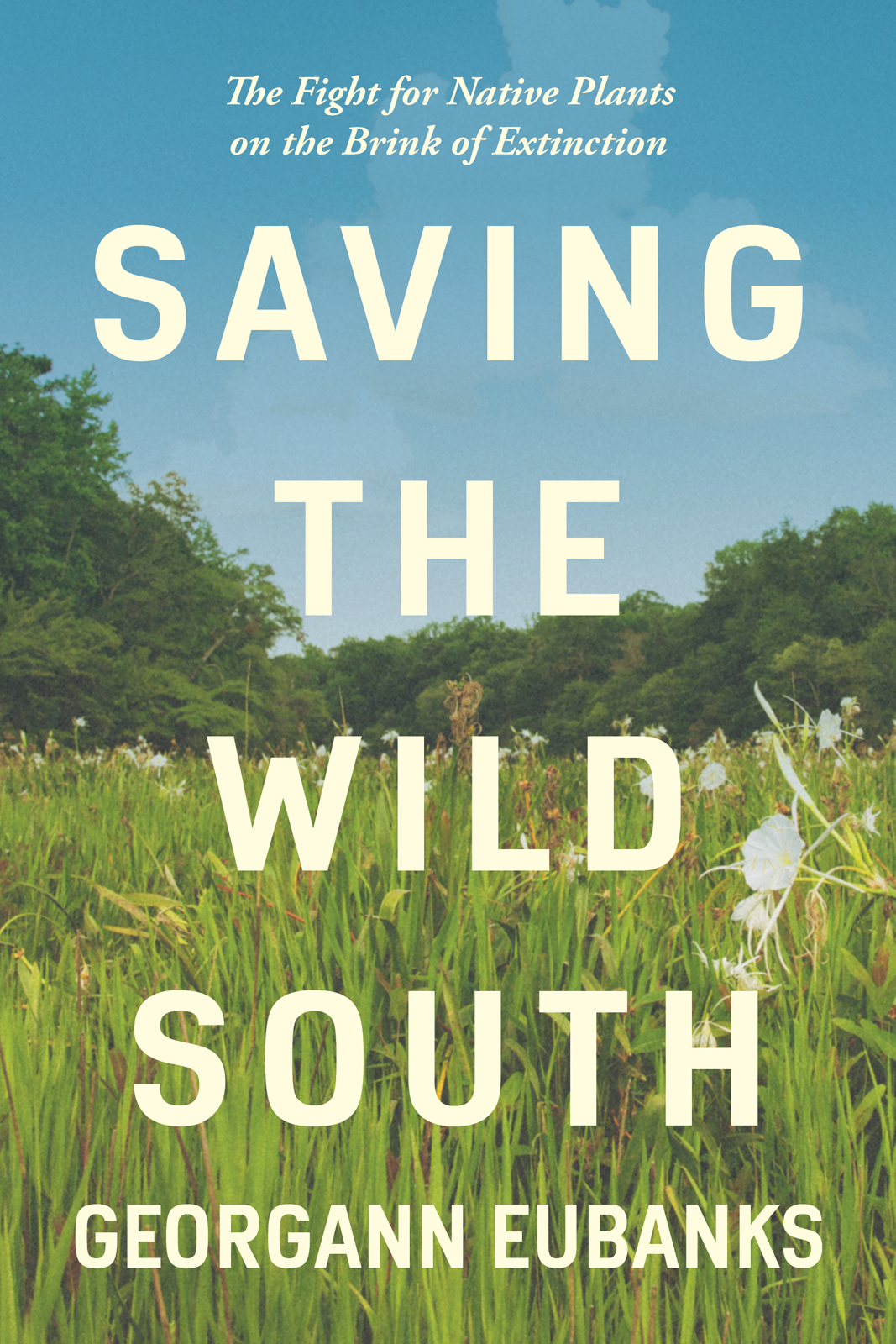

Saving the Wild South

THE FIGHT FOR NATIVE PLANTS ON THE BRINK OF EXTINCTION

Georgann Eubanks

PHOTOGRAPHS BY DONNA CAMPBELL

THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA PRESS

Chapel Hill

This book was published with the assistance of the BLYTHE FAMILY FUND of the University of North Carolina Press.

2021 Georgann Eubanks

All rights reserved

Designed by Richard Hendel

Set in Utopia and Klavika by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

All photographs, except those otherwise noted, by Donna Campbell.

Cover illustration: Cahaba lilies in Hatchett Creek in Alabama.

Photo by Elmore DeMott, www.elmoredemott.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Eubanks, Georgann, author.

Title: Saving the wild South : the fight for native plants on the brink of extinction / Georgann Eubanks ; photographs by Donna Campbell.

Description: Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021012150 | ISBN 9781469664903 (pbk. ; alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469664910 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Endangered plantsSouthern States. | Rare plantsSouthern States. | Plant conservationSouthern States.

Classification: LCC QK86.U6 E53 2021 | DDC 581.680975dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021012150

For my brother G. Ray Eubanks

explorer, mentor, scout

We could never have loved the earth so well if we had had no childhood in it, if it were not the earth where the same flowers come up again every spring that we used to gather with our tiny fingers. George Eliot, The Mill on the Floss

When we speak about the conservation of nature, we are really talking about a desire to conserve our own human identity: the parts of us that are beautiful and free and holy, those that we want to carry with us into the future. Nathaniel Rich, Climate Change and the Savage Human Future, New York Times Magazine, November 14, 2018

Contents

Figures

Saving the Wild South

In the United States, the Endangered Species Act is our principal legal tool for protecting plants that are on a trajectory toward extinction. Although the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service administers the Endangered Species Act for plants, no Federal agency, including the USDA Forest Service, can legally fund, permit, or carry out any activity that is likely to jeopardize the survival of a listed species. Once a species is listed under the Act, a recovery plan is developed that spells out actions each conservation partner can do to recover the species.

United States Forest Service

Introduction

W e live in a moment when the southeastern United States, one of the most biodiverse regions on the planet, is on the edge of redefinition. In only a few decades, we stand to lose a number of the natural features that have been a source of our identity and good fortune as a region and a people. Our lush forests, the sight and scent of blooming trillium and mountain laurel, the coastal azaleas, wax myrtles, and yaupon holly, the glory of summers dense greening, and the magic of falls deciduous palette are all at risk.

Already, many of the Souths most unusual wild plants have been reduced to small, disconnected patches of land where they can thrive undisturbed. With the effects of global temperature change and rising sea levels, they may yet be lost. This book tells the stories of a dozen such plants, already recognized as threatened or endangeredplants that are highly prized by those who study and care for them.

But why should we care? Besides their connection to our common identity as residents of the South, they are links in a chain, interdependent species that rely on other plants and animals for their well-being. Losing one is like pulling a coin out of a stack. Eventually the pillar topples.

In Smithsonian Magazine, Bill Finch, the executive director of the Mobile [Alabama] Botanical Gardens, writes: Conservation biologists are taking a closer look at the natural riches of the Southeastern United States, and they describe it as one of the worlds biodiversity hotspots, in many ways on par with tropical forests. The distinguished Harvard scientist E. O. Wilson, an Alabama native and among the first to use the term biodiversity, suggests that we need to invest more resources as a nation in preserving this regions rare plants.

This book invites readersin an intimate and accessible wayto learn more about the extraordinary natural treasures of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee. Photographer Donna Campbell and I met with botanists, conservationists, botanical garden professionals, citizen scientists, and other advocates who study and protect native plants in the wild, and we discovered a range of destinations that readers can visit where endangered specimens have been placed in conservation. Seeing these ephemeral treasures up close forced us to consider our role in their future.

In obvious and accelerating ways, human beings have created conditions on the planet that have the potential to destroy whole environmental systems. Ice caps are melting to the far north and south, sea levels are rising all around us, hurricanes are strengthening and redrawing our shorelines, droughts are more frequent and prolonged, and wildfires are more vicious and relentless. Our collective sense of safety and our capacity to protect ourselves from the ravages of wind, water, and fire are now in doubt, if not already gone. Southerners along the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts, in particular, who have been forced to rebuild time and again after more frequent and devastating hurricane damage are finally seeing the folly of big development on our shorelines. In September 2018 multiple weather experts predicted that Hurricane Florence would set a new record for East Coast rainfall. The storm dumped the equivalent of all the water in the Chesapeake Bay, mostly on North Carolina.

No surprise, then, that insurance companies are either retreating from protecting coastal properties or simply raising policy prices to impossible levels, and the US governments federal flood insurance program is insolvent and headed toward bankruptcy.

Despite our enormous human capacity for denial, it does not take much vision to see that life as we have come to know itdepending on fossil fuels and free-flowing herbicides and pesticides, on single-use plastics and nonrenewable resourcesis unsustainable. Meanwhile, the historic natural landmarks and other beloved assets in the countryside are disappearing in such a way that our identities as a diverse collection of peoples and cultures in the South are literally being erased.

I asked experts to point me in the direction of endangered plants with interesting stories, plants that might teach us something in their struggles to survive human encroachment. The southeastern United States is home to the longleaf pine savannah, once the dominant tree of 60 percent of the land from the Carolinas to eastern Texas, E. O. Wilson writes. Pitcher-plant bogs scattered through the longleaf woodland are in turn among the richest in the world, comprising up to fifteen slender-stemmed species into a square meter. We will visit these fascinating carnivorous plants and consider the loss of our longleaf woodlands in favor of the ubiquitous loblolly pine plantations, still dominant and reseeding vigorously in most places where they replaced the longleaf pines. Now, though, paper mills are disappearing dramatically in the region as cheaper sources overseas have made our homegrown pulpwood less competitive at the same time that digital communication has brought about a decline in the use of paper.