Witte de With Staff

Director

Nicolaus Schafhausen

Deputy Director

Paul van Gennip

Business Coordinator

Belinda Hak

Curators

Juan A. Gaitn, Zo Gray

Junior Curator

Anne-Claire Schmitz

Assistant Curator

Amira Gad

Education curator

Rene Freriks

Publications

Monika Szewczyk

PR and Communication

Jessie Hocks

Office

Anglique Barendregt, Gerda Brust,

Naomi Taverdin

Reception Desk

Hedwig Homoet, Erwin Nederhoff,

Erik Visser

Technicians

G Beckman, Line Kramer

Installation Team

Ties ten Bosch, Carlo van Driel,

Chris van Mulligen, Hans Tutert,

Ruben van der Velde

Interns

Renata Catambas, Jeroen Marttin,

Afagh Morrowation, Laure-Anne Tillieux,

Aleit Veenstra

Business Advisor

Chris de Jong

Board of Directors

Joost Schrijnen (chairman),

Stef Fleischeuer (treasurer),

Bart de Baere,

Jack Bakker,

Claire Beke,

Nicoline van Harskamp,

Karel Schampers,

Yao-Hua Tan

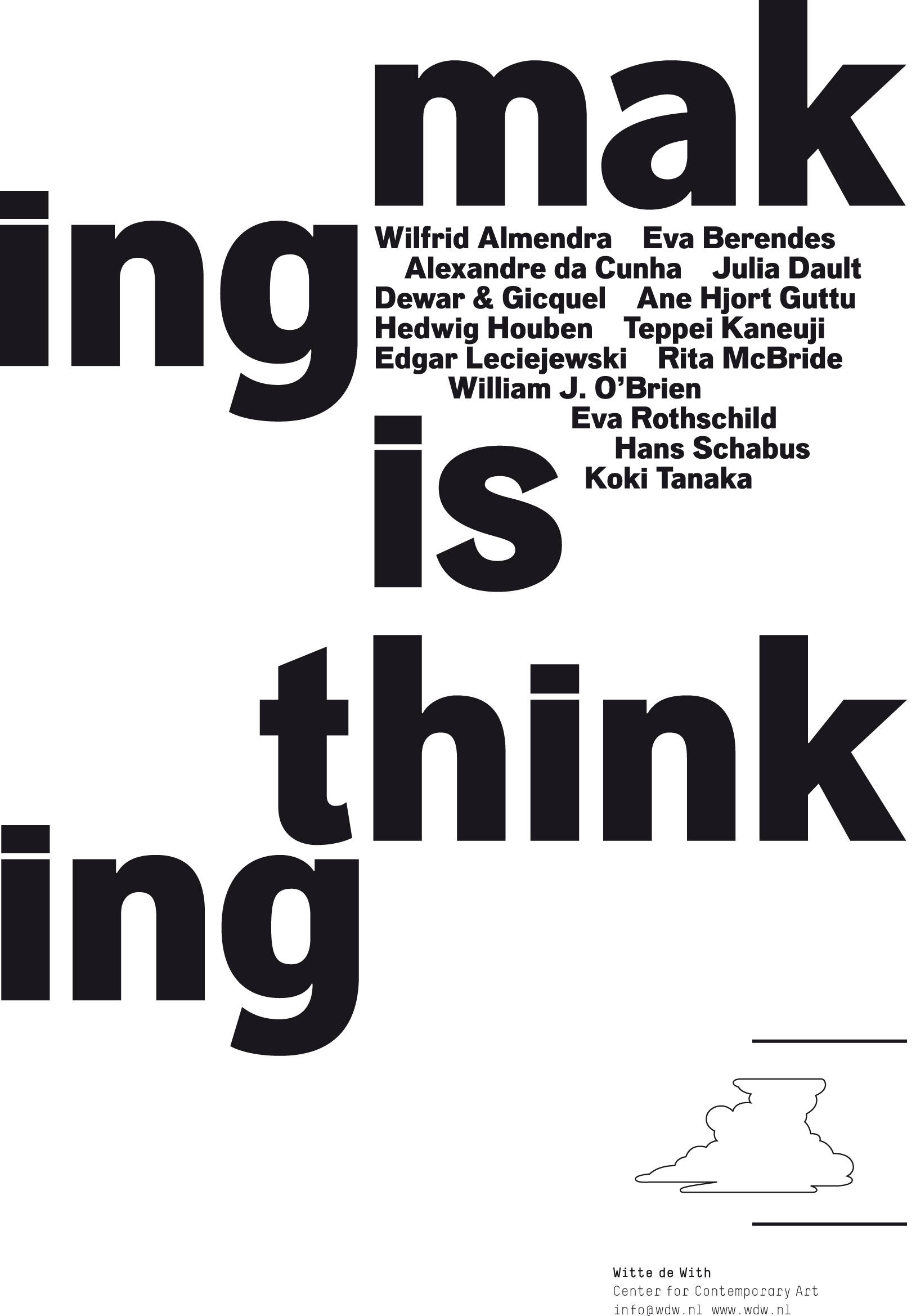

introduction

An accelerating division between making and thinking has marked European society since the Industrial Revolution. In our current digital, (allegedly) post-industrial epoch, we in the developed world are increasingly distanced from physical production. Consumer goods are manufactured far away by people we never meet, distributed through channels too complex to trace, and transported by means we never see. When our products break, we replace them, unable to fix their high-tech circuitry or rewrite their computer programs. Daily life is filtered through the screen of the television, laptop, or smartphone. Even the most symbolic entitymoneyhas become digitized, traded and placed in virtual pyramids to the point of vanishing completely.

Several movements are emerging that seek to reclaim production, to regain a sense of control by getting involved once more in the processes of making. The revival of self-sufficiency is fuelled as much by the growing debates on sustainability as by the economic recession and its accompanying conservatism. He calls for a rethinking of the hierarchical separation of workers into blue- and white-collar jobs, and a total re-evaluation of our education system, which currently privileges the creation of flexible knowledge workers over those with practical skills or manual know-how. While his vision of different vocations is rather polarized, his book convincingly traces the separation of makers and thinkers that characterized the twentieth century.

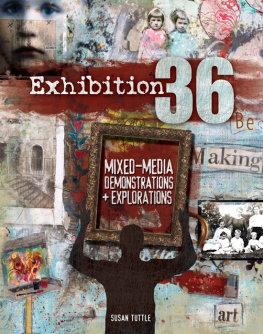

In recent years, craft has re-emerged as a way of making that offers an alternative set of values to those of industrial production, global capitalism and mass consumerism. The title of this exhibition comes from a book that makes just such a proposal: The Craftsman (2008) by Richard Sennett. Making is thinking was his maxim as he wrote the book. Sennett is a sociologist and ethnographer who has written extensively on capitalism and labor, studying the new economy and its effects on the way in which we work. His motivation for writing The Craftsman came from a desire to know what life was like for ordinary workers within the machines of contemporary capitalism. In examining the quality of work under new capitalism, Sennett asked himself what an alternative could be, and struck upon the notion of craftsmanship. Through a wide range of examples, Sennett argues that craftsmanship offers continuity between pre- to post-industrial times. For him, craftsmanship is anything that involves a literal connection between the hand and the head.

Such a reassessment of craft offers a radical way for rethinking questions of work, both within and beyond the artistic field. Strangely, neither Crawford nor Sennett explore visual art in their analysis of manual work that is intellectually rewarding. This is precisely the location at which I wish to posit this exhibition. At stake here is a paradigm for making that fuses previously oppositional positions, which I have tried to evoke by using seemingly paradoxical terms such as conceptual craft and intuitive industry. The artists included in Making is Thinking are people whose work I have encountered over the course of my travels in the past few years, from Ghent to Tokyo, Cholet to Chicago. Hailing from diverse backgrounds, their work presents alternatives to the products of the aforementioned rational, post-industrial, digitized European society. The idea for the exhibition emerged from my discussions with them and they represent a subjective selection rather than an exhaustive illustration. While each work has its own agenda, several overlapping areas of interest are discernible: There is a fascination with the role of the amateur or even hobbyist, occupied with absurdly time-consuming activities that verge on meditation (Wilfrid Almendra, Dewar & Gicquel, Teppei Kaneuji, Hans Schabus). There is an analysis of the process of creation, and its transformation into a new moment of creation (Hedwig Houben, Ane Hjort Guttu, Edgar Leciejewski). There is an exploration of sculptures relation to the applied arts and a flourishing of decoration in the reassessment of certain Modernist tropes (Julia Dault, Rita McBride, Eva Rothschild, Eva Berendes, Alexandre da Cunha). There is the avoidance of conscious thinking and the emphasis on intuition, instinct and tacit knowledge (William J. OBrien, Koki Tanaka). In many of the works there is a knowing humor or irony, which deflates the pious earnestness that can accompany discussions of craft. In all, there is a proximity to production and a keen awareness of process.

The author E.M. Forster famously asked How can I tell what I think till I see what I say?. Four writers have been invited to contribute: Alice Motard, who shares my curatorial interest in craft, will give a historical perspective by writing about William Morris. Solveig vsteb, whose exhibition Looking is Political (2009) was influential on my thinking, will interview Ane Hjort Guttu. Yoshiko Nagai, whose conversation and original way of looking at artwork I have long valued, will write a short story inspired by the work of Teppei Kaneuji. And curator Gavin Delahunty will write about thinking. These chapters and the shorter texts that follow in this guide provide some entry points into the practice of the participating artists. However, what you make of the exhibition could be another story entirely.

Zo Gray

See also Suzanne Moore, Bland leading the bland, The Guardian, 26 November 2010, p.21

According to the British Minister for Culture, Ed Vaizey, this is now the hottest book in political circles. Cited by John-Paul Flintoff in White-collar work is doomed: get your hands dirty, The Sunday Times, 2 January 2011, p.19. Flintoff continues: Michael Gove, the education secretary and David Willetts, the universities minister, are among the books biggest fans.

Matthew Crawford, The Case for Working with Your Hands, Penguin, London, 2009, p.8

Talk by Sennett at Arminius, Rotterdam, 26 November 2010.

Ibid.

Aspect of the Novel, 1927, u.p.

works in the exhibition

Alexandre da Cunha

Born 1969 in Rio de Janeiro (Brazil).

Lives and works in London.

Next page