This book made available by the Internet Archive.

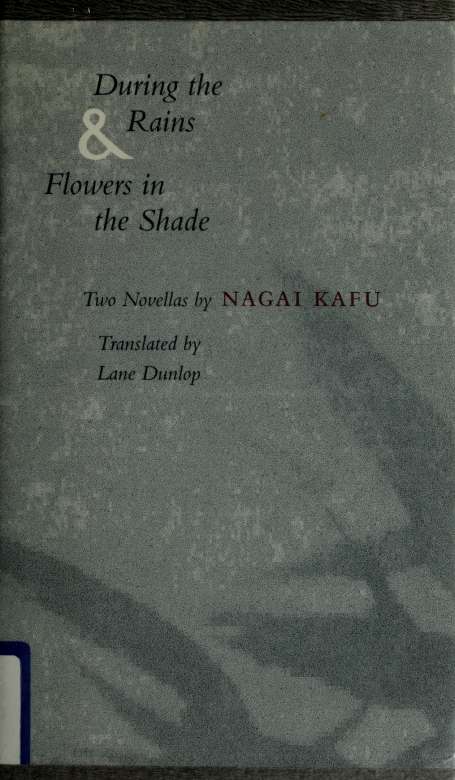

To Edward G. Seidensticker

In general admiration of his work

and in particular admiration of

Kafu the Scribbler

which introduced me to this author

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011

http://www.archive.org/details/duringrainsfloweOOnaga

CONTENTS

Translator's Preface, ix

During the Rains, 3

Flowers in the Shade, 137

TRANSLATOR S PREFACE

Nagai Kafu was born on December 3, 1879, in the Koishikawa district of Tokyo. His father, Hisaichiro, was an important Meiji-era bureaucrat; his mother, Tsune, was the daughter of a well-known Confucian scholar. The two had met and married when Hisaichiro was a student of Tsune's father.

At that time Koishikawa was in the country, an area of old estates and temples. It took its name from the brook (literally, the name means "pebble river") that still flowed above ground in Kafu's childhood. One of Kafu's early stories, "The Fox," is about a fox discovered to be living on the grounds of the family house that is ruthlessly smoked out and killed by Kafu's father and his staunch henchman, the student-houseboy. The eventual disappearance of his childhood scenes under the pavements of the city in its ineluctable expansion must have gone far to shape Kafu's sensibility. In much of his mature work, he is forever lamenting the passage of the good old days and their replacement by the bad new days.

A reluctant student who kept playing hooky to attend kabuki performances rather than university lectures, take shakuhachi flute lessons in the Yanagibashi geisha district, apprentice himself to the Edo-style playwright Fukuchi Ochi, and occasionally appear on the boards himself, Kafu steeped himself in Edo period literature and also read such foreign authors as Zola and Maupassant in English and then French. His early works include Ambition (1902), The

Translator's Preface

Flowers of Hell (1902), and The Woman of the Dream (1903). Ambition; the stqry of the rise and fall of a young Meiji businessman misled by newly imported precepts of success, is written in Kafu's peculiar variety of Naturalism, in which personal taste and evocation replace the dispassionate zeal and scientific reportage of Zola. Flowers of Hell provides an early forerunner of Tsuruko, the writer Kiyooka's wife in During the Rains, a woman educated beyond the needs of her society. The Woman of the Dream details a woman's descent into degradation and the absence of judgment that we find in the later Flowers in the Shade.

These early works, written before Kafu's departure in September 1903 for America and later France, although demonstrating that Kafu was sui generis, a writer who could not be fitted into the framework of the Naturalism and "pure literature" that dominated the Japanese literary world of the time, are not among his major works. It was his literary activity in the years following his return to Japan in August 1908 that revealed his characteristic terrain as a writer.

Kafu had been dispatched abroad by his father as a means of concealing his unsatisfactory progress along the road to conventional success and to accustom him to the discipline required for that success. To this end, Kafu worked at Japanese banks in America and France, in addition to engaging in more student-like pursuits. From his travels came Tales of America (1908) and Tales of France (1909). Most of the stories in the former are based on accounts of life in America that Kafu heard from Japanese immigrants; in the latter, hardly any Japanese appear, aside from Kafu himself in various personae. Nakamura Mitsuo, ajapanese critic, has remarked that Kafu acquired

Translator's Preface

his belief in individualism from his stay in America and his belief in traditionalism in France, where, having already been exposed to it in America, he was able to ignore the mechanical aspect of Western civilization. These beliefs were to stand Kafu in good stead when he returned to Japan, where individualism as such was not acknowledged until after the Pacific War and where until well after the Meiji era (1868-1912) civilization was equated with modernization. It is interesting to reflect that Kafu, the bulk of whose work is properly thought of as quintessentially Japanese in its evocation of the passing scenes and seasons of Tokyo, the city that found its chronicler in him, may at the outset of his career have undergone a definitive molding of his sensibility in America. The thoroughgoing individualism and natural beauty of America influenced Kafu, both in his eccentric social stance and in the sensitivity to nature evidenced in his work, long after they had disappeared as subject matter from his stories. Kafu's American-inspired individualism, among other things, may have enabled him to hold out unmoved against the patriotic hysteria of the war years.

It is with "The Fox" (1909) that Kafu's most characteristic work, with its nostalgic tone, may be said to begin. It is the first of his stories published after his return to Japan to use Japanese materials. Although short, and more of a childhood memory piece than a story, it is rightly counted among his masterpieces.

There followed a series of evocations of the vanishing past, its pleasures, pursuits, and professions: "The River Sumida" (1909), Sneers (1909-10), The Kept Woman's House (1912), Geisha in Rivalry (1917), Dwarf Bamboo (1920), and Quiet Rain (1921). Perhaps the most typical of these, as well as the most masterly, is Geisha in Rivalry. Drawing on

Translator's Preface

his experiences in the Shinbashi geisha district, Kafu depicts in detail the hfe of the geishas and their fashionable gentlemen customers, the former sympathetically, the latter critically and with a certain measure of contempt. After a decade-long hiatus, which has been attributed to Kafu's distaste for the brave new Japan, there appeared During the Rains (1931) and Flowers in the Shade (1934), his chronicles of life in the Tokyo "floating world" of the late 1920's and early 1930's. A Strange Tale from East of the River (i937) Kafu's account of his summer evening visits to a lady of the night in the Tamanoi quarter, is perhaps the most intense distillation of his longing for the past and the highwater mark of his career. It was an accomplishment he would never again achieve.

Kafu's position had its hazards. A man who always thought the past better than the present, so much so that the once bad present in due course became the good past, he entrenched himself in an anti-social solitude, which he believed to be ethically necessary. This was to yield the unexpected dividend of popularity in the years immediately following the war (thanks to his uncooperative attitude toward the wartime authorities), but it also resulted in a gradual darkening of tone, a certain cold sardonic note.

During the Rains is considered to be among Kafu's masterpieces by a variety of writers, critics, and scholars, among them Tanizaki Jun'ichiro, Nakamura Mitsuo, and Donald Keene. Edward Seidensticker, in his authoritative Kafu the Scribbler (ig6s), cites a comment by Tanizaki as the most perceptive yet made. I quote from his translation:

![Nagai Kafu - American stories: [a Japanese writers classic account of turn-of-the-century America]](/uploads/posts/book/222577/thumbs/nagai-kafu-american-stories-a-japanese-writer-s.jpg)