Family Identity and the State in the Bamako Kafu , c. 1800-c. 1900

First published 1998 by Westview Press

Published 2018 by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1997 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

This book was typeset by Letra Libre, 1705 Fourteenth Street, Suite 391, Boulder, Colorado 80304

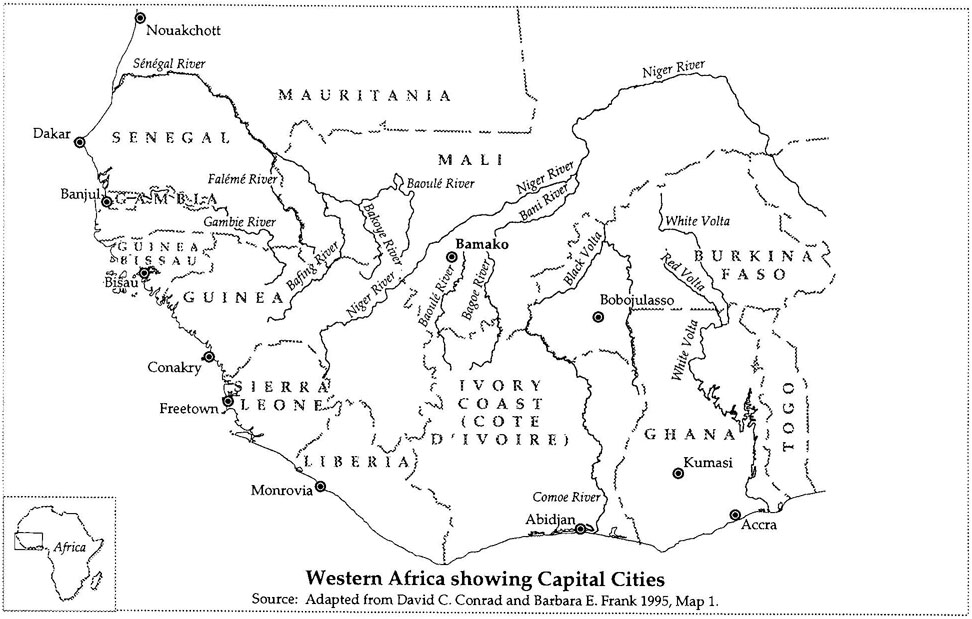

All maps adapted from sources cited by Robyn Nick.

ISBN 13:978-0-8133-3629-9 (pbk)

African States and Societies

in History

Series Editors

Philip Curtin, Paul E. Lovejoy, and Shula Marks

Family Identity and the State in the

Bamako Kafu, c. 1800-c. 1900,

B. Marie Perinbam

Landlords and Strangers: Ecology, Society,

and Trade in Western Africa, 1000-1630,

George E. Brooks

FORTHCOMING

Government in Kano, 1350-1950,

M. G. Smith

This work acknowledges a debt of gratitude to all who helped. First, I recognize the several Bamako families, the Niare, the Drave, the Ture, to mention but a few, and those of the Bamako region, such as the Kante, the Kulibaly, the Jabate, and the Keita, who graciously entered into my research, allowing themselves to be portrayed in the pages of this book. Willingly providing information, which at the time may have seemed remote, irrelevant, and downright invasive, their contributions shaped in many respects the perspectives in this book. To this extent, I acknowledge particularly Seydou Niare, Nana Niare Drave, Suleyman Drave, and Bani Toure, who were a source not only of information but also of inspiration, imagination, and hospitality. In many respects, this book is their collective portrait.

Second, beyond the circle of families, I owe special recognition to Ali Ongoba, Archivist at the Archives Nationales Maliennes, Bamako, as well as to Thiemoko Kante, Mahmadou Sarr, Seydou Camara, and Klena Sanogo, all of the Institut des Sciences Humaines at Bamako. Generous with their time and gracious beyond compare, they not only unveiled the complexities and fascinations of the vast Mande cultural worldthrowing light on the multiple regional configurationsbut they also uncovered the filigreed ideographs that incised the great cultural templates, or that had slipped practically unnoticed through the cultural crevices serrating the Mande's cultural landscape. In many respects, this book mirrors their complex, conjugated minds. Also invaluable was the assistance from other personnel at the Archives Nationales Maliennes and the Institut Fondamental d'Afrique Noire at Bamako.

Third, I acknowledge with gratitude the help of members of the jeli ( griot or bardic), mercantile and mining families, such as the Jabate and the Drame, the Sylla the Sisse and the Konate, the Kante the Dumbya and the Sissoko, whose oral recountings bespoke the peoples' lives, those who, since great antiquity, have heard the epic songs of the Do ni Kriwho heed the daily call to prayer; or who, since deep time have signed Mali's wooded savannahs "Mande"; and who still say "N'Ko," or "I say." Their voices can still be heard throughout this book.

Fourth, to the librarians at the Ecole Normale Superieure at Badal-abougou, across the Vincent Auriol Bridge from Bamako, I recall the same refrain. Tirelessly affording me repeated access to the Memoires de Fin d'Etudefor the most part a cache of invaluable oral recountings and family histories compiled by young researchers under professorial supervisiontheir indulgence enabled me to enrich poor findings only hitherto suggested, or to interrogate dubious inferences otherwise claiming authenticity, or to fill the silences left by weary, modest, or unwilling informants.

Beyond Mali and the Mande world, my acknowledgments go to the many curators, librarians, and office personnel in the offices, libraries, and archives which claimed my long research hours. In Senegal I mention particularly personnel at the Archives Nationales du Senegal and the Institut Fondamental d'Afrique Noire in Dakar; in France, those at the Archives Nationales de la France, Section Outre-Mer; at the Bibliotheque Nationale; the Centre d'Etudes Africaines (CEA), Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales; the Centre de Recherches Africaines (CRA); the Centre des Hautes Etudes sur l'Afrique et l'Asie Modernes (CHEAM); and the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS).

None of the above would have been possible without generous grant support from the University of Maryland's Graduate Research Board, the College of Arts and Humanities, and the History Department, as well as the United States Fulbright Commission. None of the above would also have been possible without the hospitality of friends in Paris, Dakar, and Bamako.

Finally, for Mande proper and place names I followed, where possible, the orthography suggested by the Direction Nationale de l'Alphabetisation Fonctionelle et de la Linguistic Applique (DNAFLA) in Bamako (e.g., "Futa Jallon" instead of "Fouta Djallon"). French words appearing in a French language context, such as proper names (e.g. "Brvi"), or those adopted into the French language such as place names (e.g. "Sngal") are accented. Appearing in an English language context, they remain unaccented (e.g. Brevie), as do also the various loan words from the Mande dialects.

B. Marie Perinbam

Mande terms for the Mande plain and mountains of the middle and upper Niger.

According to Myth and Legend

This is a story about familiesthe Niare, the Ture, the Drave, Kulibaly, Jakite, Jara, Keita, Traore, Konate, Dembele, Sissoko, Kante, Sisse, the Dembelle, and the Konare, among othersand their articulating identities in relation to a number of phenomena, most importantly the state and its associated political economies. By "state" I mean the network of incumbent families holding political power, not families sedentarized within fixed territorial boundaries. In other words, not only were familial political and ethnographic identities derived from the family and state construct. They were the state. Therefore the argument is about identity as state formation, elaboration, maintenance and renewal: the history of the state was the history of its ruling families. By "identities" I mean the development of ethnic personalities within a cultural framework and associated role-plays. I also mean the relatively condensed and thus generalized way in which individuals and groups perceived themselves and the world within which they articulated and functioned. Accordingly the history of identities is also the history of perceptions.