Traveller from Tokyo

Written with a most charming and self effacing style, this book offers readers a fascinating insight into Japan and Japanese life at the eve of its fateful entry into the Second World War.

The author, who had spent much time in India and had written on the Sikim Himalayas, was engaged by the Japanese government as an advisor to the Japanese Foreign Office in Tokyo and as a lecturer in Tokyo.

The Kegan Paul Japan Library

The National Faith of Japan D.C. Holtom

The Japanese Enthronement Ceremonies D.C. Holtom

History of Japanese Religion Masaharu Anesaki

Ainu Creed and Cult Neil Gordon Munro

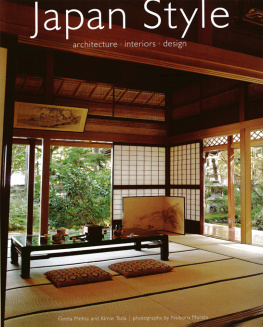

Japan: Its Architecture, Art and Art Manufactures Christopher Dresser

An Artist's Letters from Japan John LaFarge

Japanese Girls and Women Alice M. Bacon

The Kwaidan of the Lady of Tamiya James S. de Benneville

The Haunted House James S. de Benneville

We Japanese Frederic de Garis and Atsuharu Sakai

Shogi: Japanese Chess Cho-Yo

The Nighiless City of the Geisha J. E. de Becker

Landscape Gardening in Japan Jasiah Conder

Things Japanese Basil Hall Chamberlain

The Gardens of Japan Jiro Harada

Ancient Japanese Rituals and the Revival of Pure Shinto Sir Ernest Satow with Karl Florenz

History of Japanese Thought Hajime Nakamura

The Mikado's Empire W.E. Griffis

Quaint Customs and Manners of Japan Mock Joya

Beauty in Japan Samuel W. Wainwright

Behind the Japanese Mask Robert Craigie

Human Bullets Taday oshi Sakurai

In the Bamboo Lands of Japan Katharine Schuyler Baxter

Japan and Its Art Marcus B. Huish

Japanese Marks and Seals James Lord Bowes

Learning the Sacred Way of the Emperor Yutaka Hibino

The Flowers and Gardens of Japan Ella Du Cane

The Last Genro Omura Bunji

The Theory of Japanese Flower Arrangements Josiah Conder

Traveller from Tokyo John Morris

First published in 2004 by

Kegan Paul Limited

This edition published 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Kegan Paul, 2004

All Rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electric, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying or recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

ISBN: 0-7103-0886-8

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Morris, John

Traveller from Tokyo: my life in Japan, October 1939 to December 1941. New ed.

(The Kegan Paul Japan library)

1.Morris, John Homes and haunts Japan 2.British Japan 3. Japan Social life and customs 1912-1945 4.Japan Description and travel

I.Title

953'.033'092

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Applied for.

I WAS THE ONLY PASSENGER WAITING TO BOARD THE PLANE AT CAL-cutta. It was on its way across India to the Dutch East Indies. Pools of water lay all over the aerodrome, parts of which were covered with a rank growth of weeds and grass, and there was some doubt whether the plane would be able to land. The noon-day heat was almost visible; it seemed to be bubbling up out of the ground, forming small mirages, so that one could hardly tell which was real water, which imaginary.

The hot damp affected everyone and everything. Beads of moisture trickled down the walls of the concrete waiting shed, trickled down the face of the somnolent Eurasian in charge. He regarded me sleepily, without interest, as I stood on the scales, a typewriter in one hand, a suitcase in the other. Outside, a few coolies, naked except for a loin-cloth, were slowly trundling a large filling-tank, the hose of which trailed along the ground behind them. It would have lightened their work if they had wound it on to its rollers; but either this had not occurred to them, or the effort was too much trouble. They dragged the tank to the edge of the half-obscured landing marks, abandoned it and sat down to smoke. Apparently they could not read the two words of simple English that stared at them, in scarlet letters a foot high, from the side of the tank: " Smoking Prohibited."

There was no one else in sight; the whole place was as deserted as the dead Moghul cities of the north. But to me the scene was typical of my state of mind; I had reached a stage when I could see only the apathy, the deadly inefficiency, like a blight, which in time seems to affect everyone and everything in India.

I supposed I was glad to be leaving; and yet there were some regrets. It could hardly be otherwise after one had lived in a country for fifteen years. But I had lost my curiosity; and when that happens to the Englishman in India it is time for him to leave. No further experience is of any value; its only effect is to blunt the sensibility. Sooner or later there comes a time when one must accept either the standards of one's own people or those of the Indian; drift into a narrow social rut or become a native of the country. Attempts at compromise are not only intellectually dishonest, they lead to a sentimental attitude which is fatal. One begins finding excuses, condoning everybody and everything. So I was on my way to England, via Japan and the United States.

As for me, I had wanted to meet the Indian on equal terms, but I found that long years of servility and a lack of educational facilities make any sort of equal intercourse impossible; and the ramifications of caste, which it seemed we had even strengthened for our own ends, form a gulf that nothing can bridge. The only thing now left was pity: and pity alone is a poor excuse for staying in a country.

And yet undeniably there is much that is seductive about the European's life in India; the host of willing servants, ponies to ride, a large salary and very often little work. It is pleasant, too, to be treated as though one is the salt of the earth. The trouble with most people was that after a short time in the country they accepted their status without question. It is indeed difficult to refuse the greatness that is thrust upon one, especially as one becomes older, but it is vital to do so if one is to remain a civilized being. I had a feeling that I was being pulled with the force of a magnet back into the British fold. I also knew that before this happened it was imperative to escape. That was why I had decided to leave at three days' notice, and to leave by air. I wanted to put as many miles between India and myself as quickly as possible.

The huge Douglas was coming in on time. The low-lying clouds had deadened the sound of its engines, so that it seemed to appear suddenly out of nowhere. It circled twice and then landed, bumping and splashing through the puddles. Ten minutes later it was in the air again, and there below us were the drab miles of India racing by. I had resisted the pull of the magnet ; its power lessened with every minute. Looking down on the widening map I seemed to see the events of the past fifteen years unfolding beneath me, in the way that a drowning man is said to see his past. Only this was no death. Rather was it an escape from death in life, and any regrets were stifled by relief and the beauty of the scene that was unfolding beneath me.