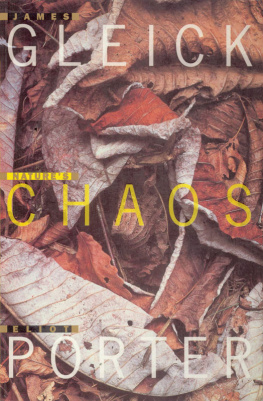

PORTER ELIOT - Natures Chaos

Here you can read online PORTER ELIOT - Natures Chaos full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Boston, year: 2001;2000, publisher: Grand Central Publishing, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Natures Chaos

- Author:

- Publisher:Grand Central Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2001;2000

- City:Boston

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Natures Chaos: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Natures Chaos" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Natures Chaos — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Natures Chaos" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Photographs copyright 1900 by Eliot Porter

Text copyright 1990 by James Gleick

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Originally published in hardcover by Viking. November 1990 First Little, Brown U.S. paperback edition, October 2001

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: January 2001

The Warner Books name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

ISBN: 978-0-7595-2118-6

James Gleick wrote the international bestseller Chaos, which was nominated for the National Book Award; Genius, a biography of Richard Feynman; and, most recently, the bestselling Faster. He edited The Best American Science Writing 2000. He was the 1990 McGraw Distinguished Lecturer at Princeton University. He has been both a science writer and a metropolitan editor for the New York Times.

Eliot Porter (19011990) was an internationally acclaimed photographer. His books include In the Wilderness Is the Preservation of the World and Intimate Landscapes, the Metropolitan Museum of Arts retrospective of Porters work. He was a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Ferns in forest, Mt. Meru, Arusha National Park, Tanzania, Africa, 8 July 1970

E ver since I became a photographer, my interest has been in the natural world. My sense of wonder was first aroused by the physical and biological mysteries of science, and when I became interested in photography the subjects that occupied my attention were those primarily connected with the natural scene. Nature became intimately associated with my perception of beauty.

To most people, I am sure, the beauty of nature means such features as the flowers of spring, autumn foliage, mountain landscapes, and other similar aspects. That they are beautiful is indisputable; yet they are not all that is beautiful about nature. They are the peaks and summits of natures greatest displays. But underlying and supporting these brilliant displays are slow, quiet processes that pass almost unnoticed from season to seasonunnoticed, that is, by those who think that the beauty in nature is all in its gaudy displays. Yet, how much is missed if we have eyes only for the bright colors. Nature should be viewed without distinction. All her processes and evolutions are beautiful or ugly to the unbiased and undiscriminating observer. She makes no choice herselfeverything that happens has equal significance. Withering follows blooming, death follows growth, decay follows death, and life follows decay in a wonderful, complicated, endless web the surface beauties of which are manifest to a point of view unattached to vulgar, restricting concepts of what constitutes beauty in nature.

When I gave up medicine for photography, I first photographed only landscapes, static subjects such as mountains and rivers that were always in the same place. Gradually I moved away from a preoccupation with views and became more and more engaged by the details. At first, I perceived the order of nature in an infinite variety of beautiful subjects. Later, however, I began to see that, in a deeper sense, individual parts of the scene were completely independent of one another in the field of living things. When I looked at nature as a whole, I realized that it had a random quality, that nothing remained as it had been, nothing could be seen as part of a unified whole. Although I was aware that it was possible to select and photograph fragments of nature that expressed the idea that nature was an orderly process, I began to realize that my photographs also emphasized the random chaos of the natural worlda world of endless variety where nothing was ever the same.

Then I read James Gleicks book Chaos, and his distillation of the new science of chaos helped me to crystallize my own thoughts about how my photographs expressed disorder in nature. After reflecting on this idea, I suggested to Janet Russek that many of my pictures seemed to be about disorder in nature, and we started to select some images for a possible book on this topic. Soon afterward Janet Russek got in touch with James Gleick when he came to speak in Santa Fe. We proposed to him that we do a book together on the disorder of nature.

When I started selecting photographs for the book from the various places I have been, including Antarctica, the Galapagos Islands, Africa, Asia, and the United States, I discovered that I had many more photographs relevant to the concept than I had originally thought. In fact, there were so many appropriate images that it was difficult to reduce the selection to an acceptable number. With Janet Russeks help, I made a preliminary selection of 250 photographs.

James Gleick reviewed the transparencies we had selected and, with his help and that of Eleanor Caponigro, the books designer, we reduced the number of photographs to about 10396 of which are previously unpublished. At that point it seemed virtually impossible to eliminate any more without discarding some that we considered especially appropriate and important for illustrating the idea. At the same time, the selection process seemed somewhat like a game of chance: it seemed to make little difference whether we eliminated a picture that was among our final selections and substituted one that we had excluded previously. This fact seemed to underscore how valid the concept of natures chaos was in connection with these photographs.

The images selected for this book are mostly details of nature which emphasize how natures apparent disorder can be reduced to aesthetically stimulating fragments. Although subjects such as mosses, lichens, or leaves that have just fallen are not orderly at all, when viewed as detailed sections, they become orderly. This process suggests a tension between order and chaos. When I photograph, I see the arrangement that looks orderly, but when you consider the subjects as a whole or on a larger scale, they appear disorderly. Only in fragments of the whole is natures order apparent.

ELIOT PORTER

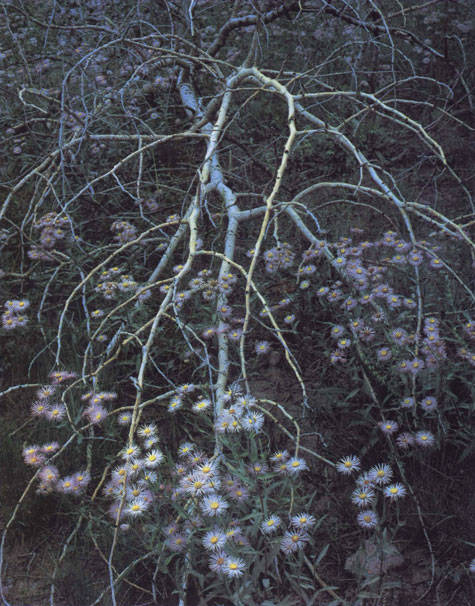

Asters and dead branch, Cumbres Pass, Colorado, 10 August 1957

W hen a child draws a tree, a green mass sits atop a brown trunk, as if the basic shape were like a Popsicle. A childs cloud is a smoothly rounded bulk, perhaps with wavy or scalloped edges. These are not the clouds we see. They are highly stylized forms, like the international symbols for Railroad Crossing or No Smoking. As children or adults, we own a repertoire of such stylized images, like ideograms in Chinese painting. First they help us seefor without such templates, our minds are powerless to sift the welter of sensations that bombard our eyes and ears. But they hinder our seeing, too. The rivers, the clouds, the snow-flakes of our usual perceptual tool kits miss much of natures true complexity: the intricate recursion, the convoluted flows within flows within flows. Our mental lightning bolts are Zs, our volcanoes are inverted and decapitated cones, our rivers are lines. Natures are not so simple.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Natures Chaos»

Look at similar books to Natures Chaos. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Natures Chaos and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.