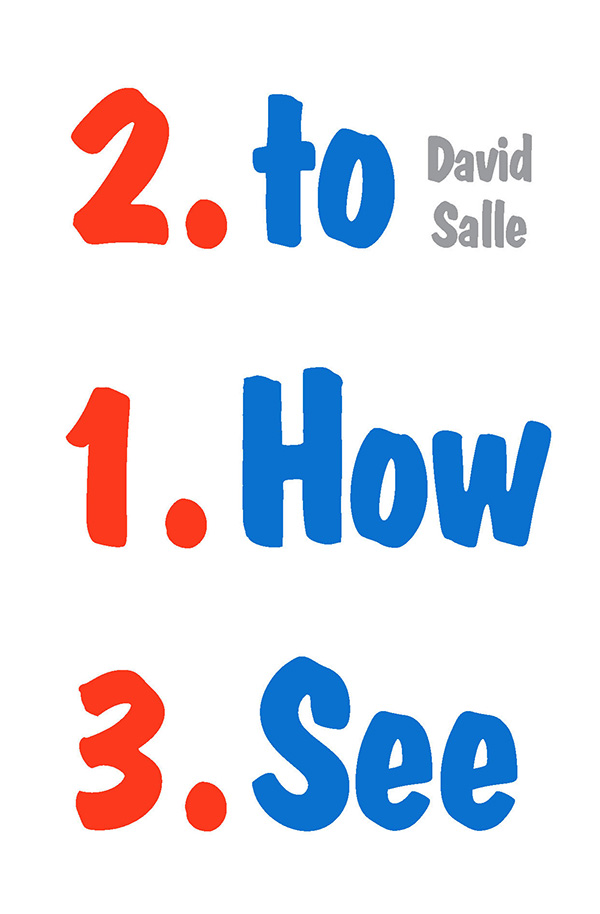

HOW TO SEE

Looking, Talking, and

Thinking about Art

DAVID SALLE

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923

NEW YORK LONDON

Copyright 2016 by David Salle

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue,

New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Helene Berinsky

Cover design by Paul Mendelsund

Production manager: Louise Mattarelliano

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Salle, David, 1952 author.

Title: How to see : looking, talking, and thinking about art / David Salle.

Description: First Edition. | New York : W. W. Norton & Company, 2016. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016025215 | ISBN 9780393248135 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Art, Modern20th century. | Art, Modern21st century. | Art appreciation.

Classification: LCC N6490 .S178 2016 | DDC 709.04dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016025215

ISBN 978-0-393-24814-2 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

M any people had a hand in launching this book. A number of these pieces were first published in Town & Country magazine, and I am grateful to Jay Fielden, then editor in chief, for the opportunity to present my ideas before a broad audience. It was something of a leap of faith on his part. This being New York, the meeting came about in an interesting way. Over a glass of wine at the Odeon one night (yes, I still go there), I mentioned to my friend the poet Frederick Seidel that I might like to do a bit of writing. Just about that dilettante-ish. He in turn said something to his friend Gemma Sieff, who had recently come on board as culture editor at T&C. After I explained what I wanted to doimpressionistic reviews, no jargonGemma was intrigued and walked me into Jays office, where a deal was struck on the spot. Gemma greatly improved the writing and has become a close friend as well.

I am grateful to Sarah Douglas, the editor of ARTNews, who encouraged me to write more long form. Thanks also to Scott Rothkopf, formerly of Artforum, now a curatorial powerhouse, and to Lloyd Wise, also of Artforum, as well Michelle Kuo, the magazines editor in chief. Thanks as well to Christopher Bollen of Interview magazine. I wish to specially thank Lorin Stein, editor in chief of TheParis Review, whose invitation to contribute to that storied journal jump-started the current cycle of work that resulted in this book. Both the piece on Amy Sillman and Questions without Answers for John Baldessari first appeared in the PR.

This book would not exist without the efforts of David Kuhn, a longtime friend who became my literary agent, and who set himself the task of seeing these essays between hard covers.

This bookas a bookis the product of my collaboration with Tom Mayer, senior editor at W. W. Norton. I am deeply indebted to Tom, and to his associate editor Ryan Harrington, who together helped give the book a coherent structure.

Thanks as well to my studio manager Mary Schwab, who wrangled the images and permissions, and coordinated logistics.

Still more people helped as readers and responders. In no particular order, I would like to thank David Wallace-Wells, Alex Katz, Michael Rips, Dan Duray, Peter Schjeldahl, Sanford Schwartz, Frederick Seidel, Rob Storr, Ben Lerner, Hal Foster and Emma Cline. Two people in particular deserve special thanks as the most patient of readers, in some cases enduring multiple drafts as well as endless questions. They are writer and editor Sarah French and novelist Frederic Tuten, great friends both. Their enthusiasm along the way made the effort seem worthwhile. Finally, I would like to thank my wife, Stephanie Manes. Her objectivity, as well as her encouragement to do better, and her delight when something hit the mark, have been invaluable.

Thank you, Dear Ones, thank you all.

W illem de Kooning, who, in addition to being de Kooning, was a genius with the English language, once likened a painting by Larry Rivers to pressing your face in wet grass. Alex Katz is another master describer; his off-the-cuff observations are fearless and precise. A failed painting might be diagnosed as having no inside energy; a painter afflicted by grandiosity is a first-class decorator, while a well-known player of the international scene makes pizza parlor art. Not all artists are so verbally gifted, or so forthright, but most of the ones I know are pretty good talkersexcept on panel discussions, where their fear of seeming insufficiently educated can make them sound dull. I know because Ive done it myself.

The idea for this book is to write about contemporary art in the language that artists use when they talk among themselvesa way of speaking that differs from journalism, which tends to focus on the context surrounding art, the market, the audience, etc., and also from academic criticism, which claims its legitimacy from the realm of theory. Both are macronarratives, concerned with the big picture. Artists, on the other hand, talk to determine what works, what does not, and why. Their focus is more on the micro; it moves from the inside out. The great contrarian film critic Manny Farber succinctly characterized the difference in his essay White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art. White elephant art was Farbers term for the self-conscious masterpiece, draped in big themes and full of content. Antonionis LAvventura, for example. The termite artist was incarnated as the director Samuel Fuller, who made several dozen low-budget, rough-and-tumble films in the 1950s and 60s. A former cartoonist, Fuller worked from his own scripts, using real locations, mostly B actors, and whatever else was at hand. The crazy beauty of his films seems almost to be a by-product of impatience. Needless to say, Farber was on the side of the diggers. His preference was for artists who burrow along, often in the dark, toward their objective, more or less unconcerned about whats happening aboveground.

Ever since Duchamp decoupled art from retinal experience early in the last century, there has been a misapprehension about the relationship between means and ends. Critical writing in the last forty or so years has been concerned primarily with the artists intention, and how that illuminates the cultural concerns of the moment. Art is treated as a position paper, with the artist cast as a kind of philosopher manqu. While that honorific might in some instances be well earned, the focus on intention has led to a good deal of confusion and wishful thinking. A visit to any of todays leading art schools would reveal one thing in common: The artists intent is given far greater importance than is his or her realization, than the work itself. Theory abounds, but concrete visual perception is at a low ebb. In my view, intentionality is not just overrated; it puts the cart so far out in front that the horse, sensing futility, gives up and lies down in the street. Intent is very elastic in any case; it can stand for a variety of aims or ambitions. What has a greater impact on style is how an artist stands in relationship to his or her intention. This may sound complicated, but its not.

Next page