I take thankful pleasure in acknowledging the unsparing assistance of more than forty Mexican artists of my acquaintance. Having made the writing of this book inevitable, by virtue of producing so many distinguished works, they enabled the process of its completion by their hospitality and generously disposed resources.

For making it possible for me to meet so many painters under friendly auspices I have to thank the seorita Ins Amor, owner and director of the Galera de Arte Mexicano in Mexico City; the seora del Valle, curator of the University Art Gallery; seor don Alberto Misrachi of the Central de Publicaciones ; and seor don Samuel Mart, an artist in the field of music who both initiated and shared many of my adventures of discovery and appreciation amongst the plastic arts.

Eight of the line drawings by Carlos Orozco Romero which appear here as headpieces to the several chapters were published in 13 Mexican Painters , a small folio produced in Mexico City in 1939. The other two were drawn especially for this book. The original portrait studies are all in my possession. Most of the photographs used for the reproduction of mural and easel paintings came from the studios of Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Abraham Gonzalez, Edwin Johnson, Luis Limn and Juan Arauz Lomeli, and from Foto Gmez, Mexico City. The lithographs and etchings reproduced in the last chapter were photographed by Robert M. Catlin, Jr.

I acknowledge with thanks the permission of Messrs. Covici-Friede to quote from the Introduction to Diego Riveras Portrait of America ; of the Macmillan Company to quote from John Taylor Arms Introduction to Four Hedges: A Gardeners Chronicle by Clare Leighton.

To Mr. and Mrs. Henry M. Winter of New York and Miss Anna Penney of Boston I am grateful for assistance in the ordering of manuscripts, both at home and abroad.

MacK. H.

EPILOGUE

(for Bill Estler)

I HAVE SAID THAT FROM THE POINT OF VIEW OF THE Mexican artists themselves there is, properly speaking, no Mexican school of painting. There is more diversity amongst them than a school logically comprehends. There once was, if you like, a Rivera school, but that existed at a time when the master did most of the painting and the pupils merely held the brushes. Ultimately, every good Mexican artist has gone pretty much his own way.

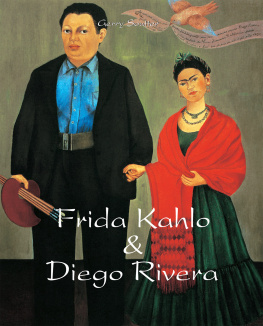

Even the muralists, for all their syndicates and associations, have not been coherently related by any really persuasive identity of object. The Rivera wing of the mural movement has been labeled literary and political, but Diego himself has rarely allowed his interest in plastic forms to be finally distracted by the ideas conveyed in them. On the whole, Rivera has made a nicely balanced approach to the problem of equalizing the logical and pictorial elements of representational painting. Opposed to him on the left flank, openly accusing him of both ideological and plastic timidities, were younger artists who more frankly, if usually with less technical proficiency, propagandized the Revolution. His chief adversary on the right flank, Jos Clemente Orozco, was intellectually indifferent to the common ideas of his time. He cared for them only as they were susceptible of translation into pictorial and emotional values.

As for the Solitos, I feel I have nearly done violence to actuality in reducing the real disparity amongst them by arranging them, to meet the needs of bookmaking, in conventional chapters. Some of them do, it is true, fall into recognizable categories, especially the Mexicanists and the suprarealists; but there is today only one consciously coherent group of artists, the politically minded print-makers of the Taller de Grafica Popular.

On the other hand, there are invariable qualities which have been observed in all good modern Mexican art by people who have lived amongst the artists and their works: qualities which establish a given work as Mexican and modern. I have tried to show that these qualities are not necessarily dependent upon the treatment of specifically Mexican subject matter; that a picture which gets its Mexican stamp from a representation of a plaza or a market place dressed up for a festival is only superficially Mexican. The recognizable identificality of a Mexican work of art depends upon something more personal than subject matter taken from the outward scene, something not to be perceived as quaint or picturesque or cute. It proceeds from the inherent structure of the temperament or disposition of the Mexican artists, or is invoked by an atmosphere which stimulates their creative impulses. Three of its outward signs are earnestness, sincerity and unworldliness. Yes, in spite of its aggressive secularity, it is unworldly. The inward and spiritual gift which animates the work is taste, nourished by familiarity with noble antecedent cultures.

I have suggested that three predominant feeling tones are appreciable in the whole range of modern Mexican art: mysticism, pessimism and a strongly inhibited, melancholily conditioned mirth. But the presence of one or another of these feeling tones is not a certain guide in the detection of specifically Mexican qualities, because they appear in the pictures unequally and variably. The ultimate invariable quality or character of a convincingly Mexican work of art is its vitality.

Everybody I know who has made a sympathetic study of the Mexican pictures and has had the experience of living amongst them has put vitality in the first category of appreciation. Alma Reed, a distinguished patroness of Mexican art, wrote in her Foreword to the catalogue for the Macy show in 1940, Probably no national art in the world today has the vitality of the art of Mexico. The Mexican pictures of which I have been speaking are all alive and communicate to the observer the excitement of partaking in their animation.

There is, strictly speaking, no regional painting in Mexico, for the reason that the best painters live in Mexico City. But every man amongst them is rooted in the soil and has been fostered by the traditions of his country. He has created his works of art out of intimate and acute experience of the contemporary life and the living past of a country which is being reborn. The vitality of the new democratic race of Mexicans has been urgent enough to awaken even Indian artists from their natural drowsiness.

To the spectator from the North, accustomed to a European tradition which has assumed technical excellence as an essential means, much of the Mexican painting may seem, at first glance, not altogether proficient. There is precious little virtuosity in Mexico, there is even too little sacrificial taking of pains. But more than two-score living Mexican artists have got something that practice, competence and technical proficiency can never in themselves produce. They have the supreme gift of translating experienced emotion into works of art which give off emotion. And that, I take it, is what those of us are after who go to look at pictures.

CHAPTER ONE

Dr. Atl, the Saint John Baptist of Mexican Art

Subi al Popocatpetl,

Baj del Ixtacchuatl,

Y es hombre de gran valer

el inquieto Doctor Atl.

From a Fa-cha caricature

THE HARBINGER OF THE MODERN Mexican art movement was not the sybarite himself, Diego Maria de la Concepcin Rivera who later possessed it, but a half-legendary little man who is said in the popular tradition to inhabit a cave in the side of Popocatpetl. When I lived in Cuernavaca, in daily sight of Popos snow-capped cone, I was almost persuaded to look for him there. I thought I should be able to recognize, at sight, the bearded face and bulging forehead of his innumerable self-portraits. I could imagine him, his smock exchanged for leathern girdle, eating his dinner of locusts and wild honey at the edge of the volcanic funnel whence, according to the local folklore, he was erupted, more than sixty years ago, into a tumultuous world.

![Robertson Bruce - Lives of the artists: [masterpieces, messes (and what the neighbors thought)]](/uploads/posts/book/163588/thumbs/robertson-bruce-lives-of-the-artists.jpg)