Baseline Co. Ltd

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers, artists, heirs or estates. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

I. Dawn of the Mural Renaissance

Towards a National Art

The Mexican murals of the 20 th century were not a freak flare-up lighted by the bonfire of a revolution. However, a national style was not at all in evidence as the movement began. By 1920 decades of successful official pressure had succeeded in stifling Mexican aesthetics, or at any rate in running them underground into the subconscious. When the time came for the young revolutionaries to re-establish a link to their plastic heritage, they went through pangs of pioneering and blind progress, which have earned the movement its name of renaissance or rebirth.

To study the Mexican school of painting that immediately precedes the mural era, impregnated by Indian, colonial, and popular tradition, is to witness the awakening of a national plastic language, perhaps more important in its trend than in its actual results. The nationalist movement, whose fate was to be overshadowed by the greater daring of the muralist group, dared a great deal during the short season that it reigned unchallenged. It proved a substantial instrument in switching the taste of a lay public from the veneration of European bon ton to claims of a racial aesthetic. The Mexican renaissance would scarcely have flourished if this previous stream of Mexican art had not flowed its way.

Throughout the 19 th century pictures were painted with Mexican subject matter, featuring popular costumes and mores. The costumbristas, artists like Hesiquio Iriarte and Casimiro Castro, were more adept at the graphic mediums than at painting. They left us an encyclopaedic survey of 19 th -century Mexico in albums of lithographs, some hand-coloured, and a few pictures, now housed in the historical museum of Chapultepec. But, prophets in their own country, they remained without honour in their time, their works embedded anonymously in the plentiful and ever-varied folk production.

It took the recognised fine arts a long time to contact, unashamed, the Mexican milieu. The critics saw further ahead than the artists, and a leitmotiv runs through writings on art in the mid-19 th century, a sighing for a national art to match the national independence that had just been realised. When in 1869 Petronilo Monroy exhibited his allegory The Constitution of 57, a flying female in Pompeian drapes, critics admired it but suggested: Beautiful as it may be, is it not time that our artists exploit the dormant wealth of our own ways of life, both old and new.

Once the revolution of 1910 came about, the paradox of a majority of painters unaware of the national pride that shook their native hearth became acute. Manuel Gamio complained in 1916: Painters copy Murillo, Rubens, Zuloaga, or still worse paint views of France, Spain, Italy, if need be of China, but hardly ever do they paint Mexico. Hardly ever shows that Gamio was aware of exceptions to his statement. The contemporary plastic rediscovery of Mexico had already begun when he spoke those disheartened words.

In 1907 the young provincial painter Jorge Enciso had come from his native Guadalajara to seek his fortune in the capital. That he needed it is suggested by El Kaskabel, a jocular tapato (colloquial term for a person from Guadalajara) sheet, which swears that the artist made the memorable trip clinging under a boxcar, with his pictures rolled inside a pillowcase since he had no trunks but those he wore.

At the time, serious art students, driven by the applause of enlightened amateurs and the photographic ideals of Maestro Fabres, were preparing to paint musketeers as jaunty as those of Roybet, odalisques as pink as those of Gerome, and grenadiers as martial as those of Meissonnier. Unaware of this ambition, Enciso on arrival unrolled the fruit of his young lifes work in the studio of Gerardo Murillo with whom he roomed, and soon opened a one-man show in Calle de San Francisco, No. 3, fourth floor. Three rooms were piled high with over 250 items, oils, pastels, charcoal and lead pencil drawings. On the cover of the catalogue a gentle china poblana bowed to her public before a background of nopales; green and red on white, the colours of the Mexican flag emphasised the national flavour.

All the pictures were on Mexican themes and of great simplicity. They were mostly landscapes, often merely a bare wall or a cubic house, with a few faceless people bundled in sarape or rebozo, their backs turned, unaware that they are being watched. Titles suggested the mood: Muse of Dawn, To Mass, Old House. An instant success, the show in its simplicity punctured the badly aimed pretension of the Fabres group, raising the grave question of a national art.

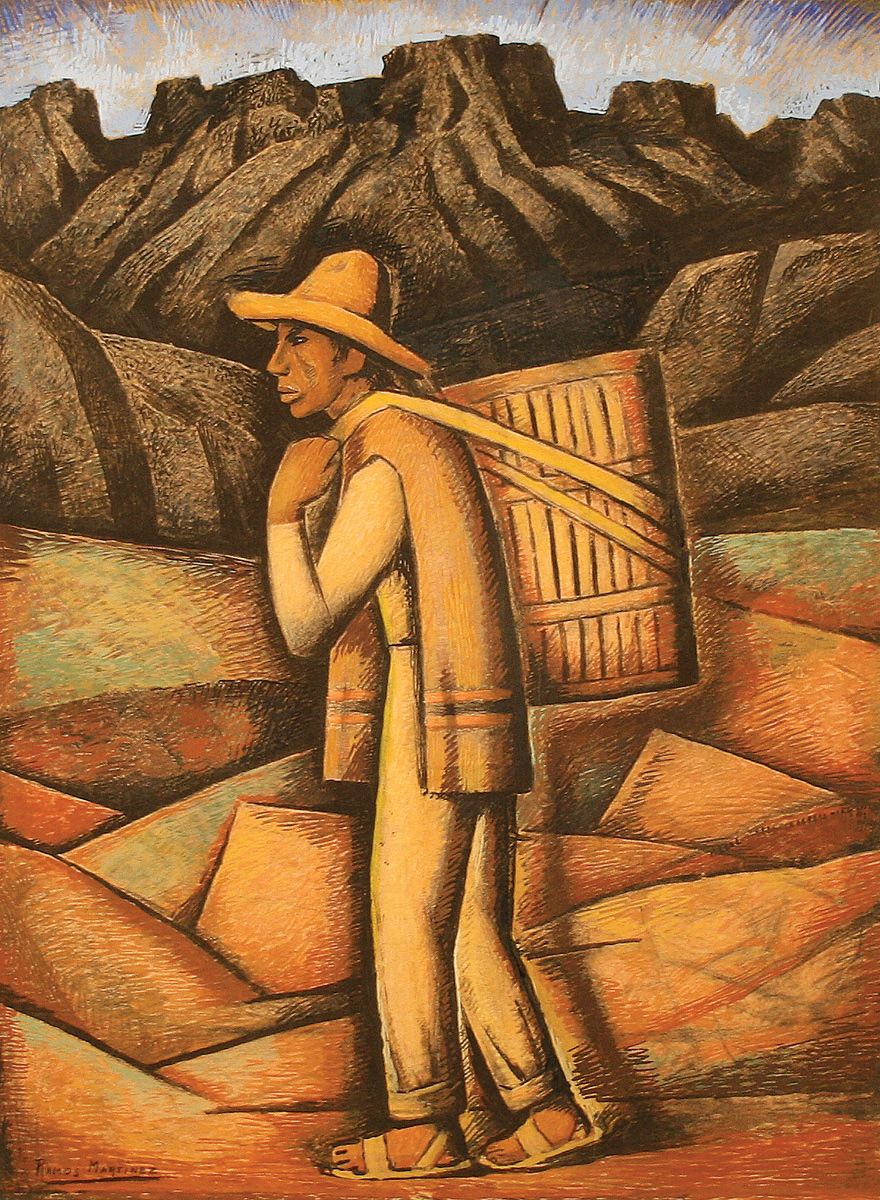

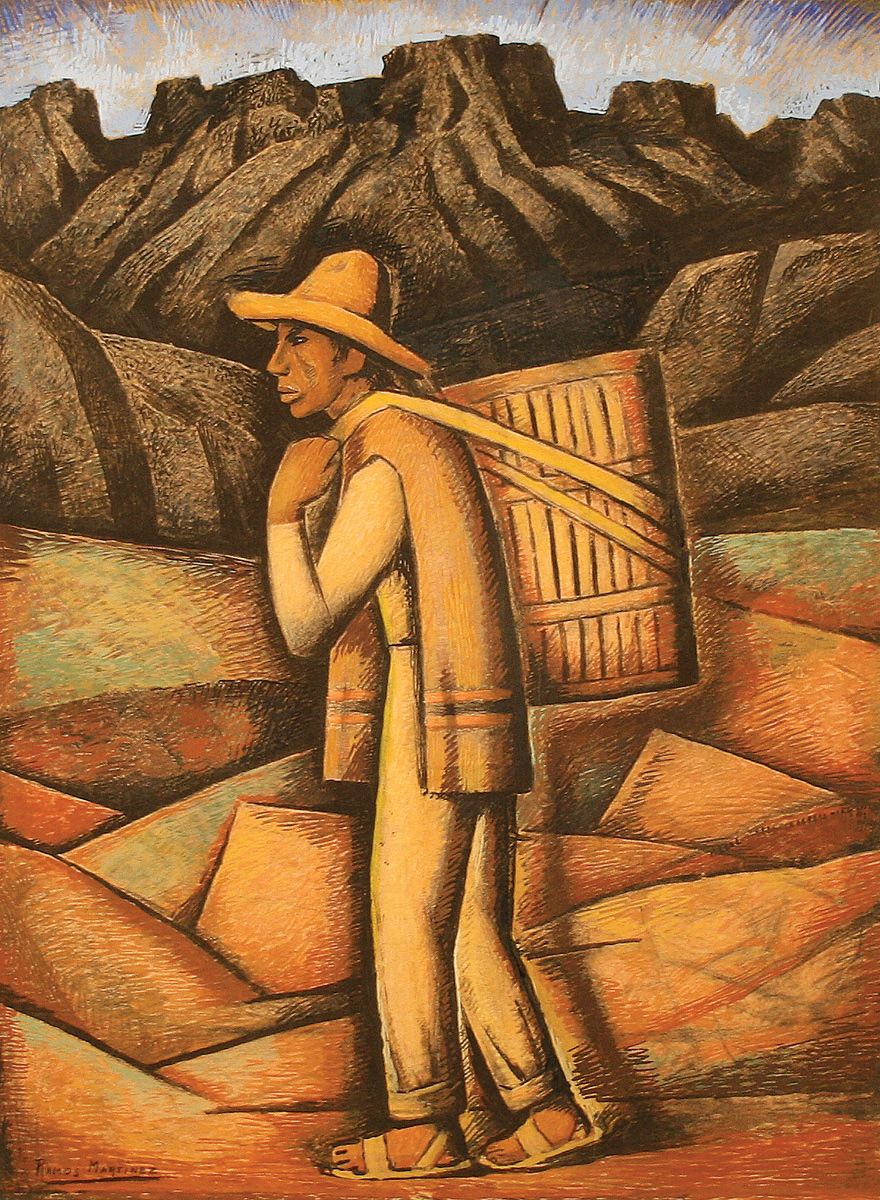

Alfredo Ramos Martnez, Returning Home from the Market, c. 1940. Mixed media, tempera and charcoal on paper, 67.3 x 51.1 cm. Location unknown.

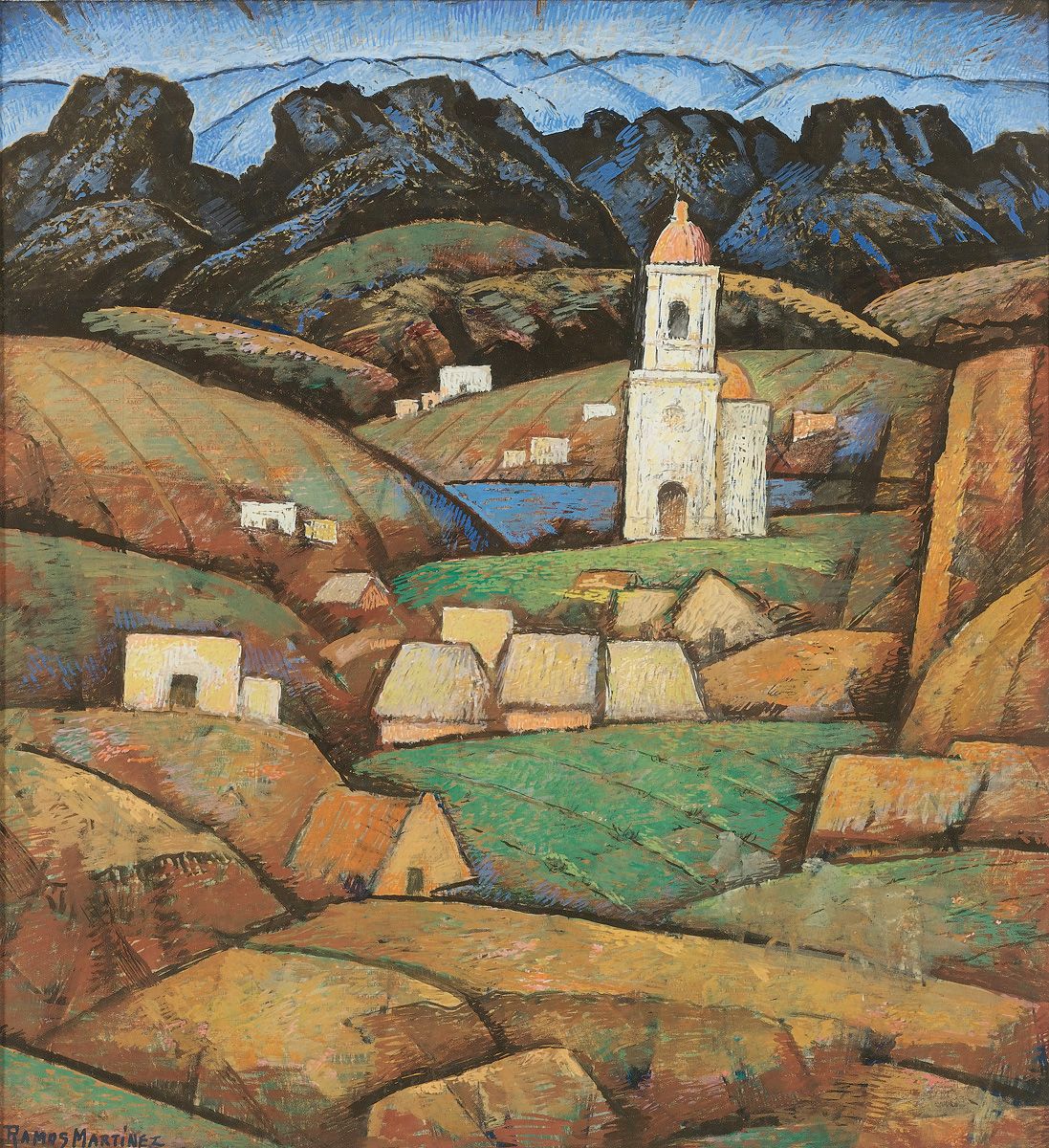

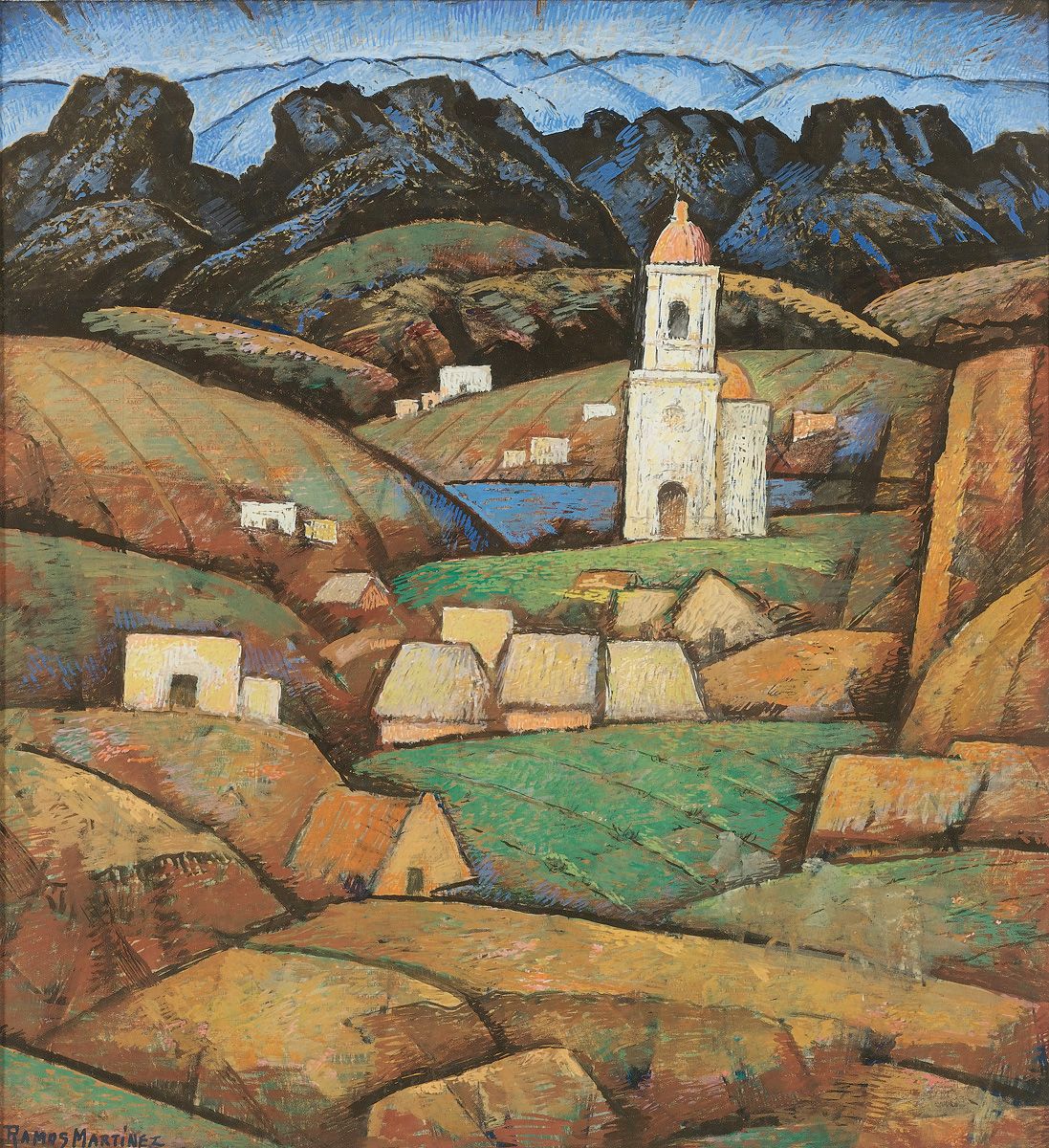

Alfredo Ramos Martnez, The Little Chapel, date unknown. Tempera on newsprint laid down on board, 45.7 x 43.2 cm. Dalzell Hatfield Galleries, Los Angeles.

Besides contemporary landscapes, Enciso revived ancient Aztec themes. Such was The Three Kings, with flowing quetzal plumes for headdresses, the figures holding copal censers. Such themes inspired the poet Jos Juan Tablada, who saw the artist and his Indian subject matter as one: The Eyes of Enciso are made of obsidian, sharp and brilliant as the silex arrows soaked in the fire of a star... Brown and agile as an Aztec bowman, the artist resurrects the prodigy of Ilhuilcamina... Arrows shot from his eyes blast stars from the firmament.

Enciso also painted the first 20 th -century murals with Amerindian content. Painted directly on the walls of two schools, one for boys and one for girls, in the not so aristocratic Colonia de la Bolsa, they were begun in December of 1910 and finished on 16 May 1911. They were destroyed when the buildings were remodeled.

His evaluation still holds good. After he became conservator of colonial buildings, the artist stopped painting in 1915, but his influence remains an active factor in Mexican art.

Another pioneer, Saturnino Herrn, painted in a manner that states, even if it fails to solve, the problem of a national style as distinct from the stressing of local colour. Born in 1888 and dead at thirty, Herrn, during his short life, was a not too successful painter, rounding out a meagre income with a life class at the Academy of San Carlos. Making virtue of necessity, Herrn never left Mexico, never failed to paint Mexican themes. Typical of his work is