Note to the Reader on Text Size and the main things that happened were miles and the time of day We recommend that you adjust your device settings so that all of the above text fits on one line; this will ensure that the lines match the printed book and the authors intent. If you view the text at a larger than optimal type size, some line breaks will be inserted by the device. If this occurs, the turn of the line will be marked with a small indent.

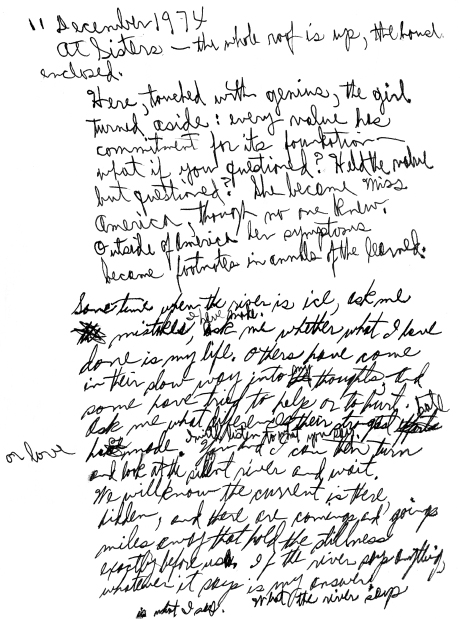

First draft of Ask Me, December 11, 1974 (reduced). From the William Stafford Archives.

POETRY Another World Instead: The Early Poems of William Stafford 19371947 The Way It Is: New and Selected Poems Even in Quiet Places My Name Is William Tell Passwords An Oregon Message Smokes Way A Glass Face in the Rain Stories That Could Be True Someday, Maybe Allegiances The Rescued Year Traveling through the Dark West of Your City PROSE Every War Has Two Losers: William Stafford on Peace and War Crossing Unmarked Snow: Further Views on the Writers Vocation The Answers Are inside the Mountains: Meditations on the Writing Life You Must Revise Your Life Writing the Australian Crawl: Views on the Writers Vocation Down in My Heart: Peace Witness in War Time

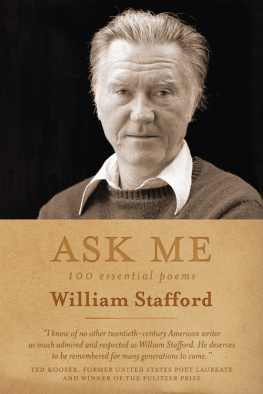

ASK ME

100 Essential Poems WILLIAM STAFFORD Edited by Kim Stafford Graywolf Press Compilation copyright 2014 by the Estate of William Stafford Introduction copyright 2014 by Kim Stafford Poems included in this volume were previously published in The Way It Is: New and Selected Poems (Graywolf Press, 1998) and Another World Instead: The Early Poems of William Stafford 19371947 (Graywolf Press, 2008).

This publication is made possible, in part, by the voters of Minnesota through a Minnesota State Arts Board Operating Support grant, thanks to a legislative appropriation from the arts and cultural heritage fund, and through grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Wells Fargo Foundation Minnesota. Significant support has also been provided by Target, the McKnight Foundation, Amazon.com, and other generous contributions from foundations, corporations, and individuals. To these organizations and individuals we offer our heartfelt thanks.  Published by Graywolf Press 250 Third Avenue North, Suite 600 Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 All rights reserved. www.graywolfpress.org Published in the United States of America ISBN 978-1-55597-664-4 Ebook ISBN 978-1-55597-325-4 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 First Graywolf Printing, 2014 Library of Congress Control Number: 2013946920 Cover design: Jeenee Lee Design Cover photo: Robert B. Miller

Published by Graywolf Press 250 Third Avenue North, Suite 600 Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 All rights reserved. www.graywolfpress.org Published in the United States of America ISBN 978-1-55597-664-4 Ebook ISBN 978-1-55597-325-4 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 First Graywolf Printing, 2014 Library of Congress Control Number: 2013946920 Cover design: Jeenee Lee Design Cover photo: Robert B. Miller

Preface

William Stafford was born in 1914, the first year of the Great War.

As a child, he heard drums in the military parade. At the edge of town, he watched the Klan march. He chopped weeds in the sugar beet field. He worked in an oil refinery. His paper route sustained the family for a time. And when he started writing during World War II, in a camp for conscientious objectors, he wrote about trees, and evening, and quiet at the margins.

He wrote about the citizens of Dresden. He was spared the need to hate. Something deeper was at stake. A hungry reader of philosophy, his lifelong companions were Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, Pascal, and Wittgenstein. But so were the thousands who sent him their poems, and received an immediate reply. Lets talk recklessly, he would say.

He wrote rituals, notes, lists, gestures, letters, poemsand invited others into those spaces. I must be willingly fallible, he wrote, to deserve a place in the realm where miracles happen. At a reading, he would hold up his left hand, starting into a poem: This is the hand I dipped in the Missouri. Or if he found himself in another country, he would name the local river. In the poem that gives this book its title, he wrote, What the river says, that is what I say. He read these poems in Iran under the Shah, in Poland, Egypt, Pakistan, India, Nepal.

With his habit of writing every day before dawn, he composed twenty thousand poems. Of these, four thousand were published in magazines. He had a cardboard box in his office labeled Abandoned Poems. When I reached in a few days after my father died to take one at random, it was startling, imperfect, exploratory. I remembered his claim, I would trade everything I have ever written for the next thing. He traveled for poetrysometimes thirty readings in thirty days.

He was an ambassador for the possibility of peace through poetry. The calendar was black with engagements. At a reading, following one of his deft, quiet offerings, a listener helplessly spoke aloud, I could have written that. And William Stafford, looking kindly at the speaker, replied, But you didnt. A beat of silence. But you could write your own.

You could write your own. What a democratic idea. Each of us could write our own poem, our own proposal for peace, our own aphoristic meditation at the un-national monument, our own consolation, manifesto, blessing. The field of writing will never be crowded, he told me once, not because people cant write, but they dont think they can. His life as teacher and witness and corresponding friend advocated the pen in hand, the moving pen, your own way of looking at things. A hundred years after his birth, from the fifty books he published in his lifetime and the dozen published since, Ask Me offers these one hundred essential poems of William Stafford, from the indelible scene described in Traveling through the Dark to the challenging questions presented in You Reading This, Be Ready.

This book will help us all be ready. The greatest ownership of all, he said, is to look around and understand. For us, poem by poem, he looked at the worldand the world was mysterious, dark, enticing. Kim Stafford

ASK ME

A Story That Could Be True

If you were exchanged in the cradle and your real mother died without ever telling the story then no one knows your name, and somewhere in the world your father is lost and needs you but you are far away. He can never find how true you are, how ready. When the great wind comes and the robberies of the rain you stand on the corner shivering.

The people who go by you wonder at their calm. They miss the whisper that runs any day in your mind, Who are you really, wanderer? and the answer you have to give no matter how dark and cold the world around you is: Maybe Im a king.

Fifteen

South of the bridge on Seventeenth I found back of the willows one summer day a motorcycle with engine running as it lay on its side, ticking over slowly in the high grass. I was fifteen. I admired all that pulsing gleam, the shiny flanks, the demure headlights fringed where it lay; I led it gently to the road and stood with that companion, ready and friendly. I was fifteen.

We could find the end of a road, meet the sky on out Seventeenth. I thought about hills, and patting the handle got back a confident opinion. On the bridge we indulged a forward feeling, a tremble. I was fifteen. Thinking, back farther in the grass I found the owner, just coming to, where he had flipped over the rail. He had blood on his hand, was pale I helped him walk to his machine.

He ran his hand over it, called me good man, roared away. I stood there, fifteen.

Vocation

This dream the world is having about itself includes a trace on the plains of the Oregon trail, a groove in the grass my father showed us all one day while meadowlarks were trying to tell something better about to happen. I dreamed the trace to the mountains, over the hills, and there a girl who belonged wherever she was. But then my mother called us back to the car: she was afraid; she always blamed the place, the time, anything my father planned.

First draft of Ask Me, December 11, 1974 (reduced). From the William Stafford Archives.

First draft of Ask Me, December 11, 1974 (reduced). From the William Stafford Archives.  Published by Graywolf Press 250 Third Avenue North, Suite 600 Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 All rights reserved. www.graywolfpress.org Published in the United States of America ISBN 978-1-55597-664-4 Ebook ISBN 978-1-55597-325-4 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 First Graywolf Printing, 2014 Library of Congress Control Number: 2013946920 Cover design: Jeenee Lee Design Cover photo: Robert B. Miller

Published by Graywolf Press 250 Third Avenue North, Suite 600 Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 All rights reserved. www.graywolfpress.org Published in the United States of America ISBN 978-1-55597-664-4 Ebook ISBN 978-1-55597-325-4 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 First Graywolf Printing, 2014 Library of Congress Control Number: 2013946920 Cover design: Jeenee Lee Design Cover photo: Robert B. Miller