The Way It Is

Theres a thread you follow. It goes among

things that change. But it doesnt change.

People wonder about what you are pursuing.

You have to explain about the thread.

But it is hard for others to see.

While you hold it you cant get lost.

Tragedies happen; people get hurt

or die; and you suffer and get old.

Nothing you do can stop times unfolding.

You dont ever let go of the thread.

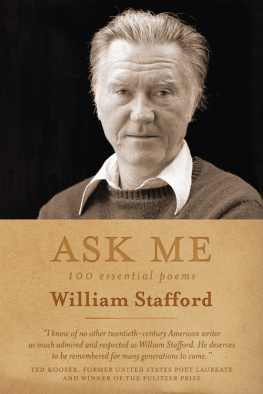

William Stafford

19141993

Published by Trinity University Press

San Antonio, Texas 78212

Copyright 2002, 2013 by Kim Stafford

The original publication of this book was made possible in part by a grant provided by the Minnesota State Arts Board, through an appropriation by the Minnesota State Legislature, a grant from the Wells Fargo Foundation Minnesota, and a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. Significant support has also been provided by the Bush Foundation; Marshall Fields Project Imagine with support from the Target Foundation; the McKnight Foundation; and other generous contributions from foundations, corporations, and individuals. To these organizations and individuals we offer our heartfelt thanks.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-59534-186-0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2002102959

Cover design: Christa Schoenbrodt, Studio Haus

Cover photograph: William Stafford (photographer unknown)

I ts morning, before first light, 1965. Im with my brother Bret at the tailgate of the family station wagon on the gravel shoulder of a road. We grope by dark in the back of the car where our bikes lie tangled in a heap, the pedals and handlebars locked together. We drag them out, work them free, then stand them side by side.

Ready? Our fathers voice from the dark.

I guess so. My brother.

You lucky kids. Our father puts one hand on my shoulder and another on my brothers. Im shivering, partly with joy. Daddy has given up his writing time before dawn and brought us to the top of Chehalem Mountain, so we can start our bike ride to the Pacific with a long coast downhill. The real work, the climb over the mountains and the thickening traffic, will come later, but he has given us this easy beginning. Then he is in the car, turning back across the road, heading east, and we watch his taillights dwindle toward home.

My brother is older, so he goes first, clambering onto his bike and gliding west down the dark road. He disappears into the gloom. Then its me in a rushcold wind in my face, knuckles clamped, damp smell of the forest, gravel popping from the wheels. In time, the sun rises behind us, touching everything green with goldfields and trees, a blur of mailboxes, the dashed centerline of the road. Then sweat. Fire in my lungs. My brother a speck at the top of the roads long climb. No water. That tight passage called the Van Duzer Corridor where giant trees crowd the twisting highway. Cars on a curve ripping past within inches, and my wheels skidding in gravel toward the ditch.

How long can you feel a hand, steady on your shoulder, after that hand pulls away?

A few days after my father died, I needed to sleep alone at the home place, to go back to the room I shared with my brother when we were young. Mother was away. I came to the house after dark, found the hidden key. In the home labyrinth, your feet know the way. Down the hall in the old garage, I turned into the study my father had built, where I stood a moment: dark walls, dim rows of books, papers on the desk, the making place. Then up two steps to the kitchen, a turn down the hall, and into the room of childhood.

For the first time in years, I slept deeply from the moment I lay downuntil I woke at around 4 a.m. Mother had told me that since his death she, too, had been wakened at my fathers customary writing time. As I opened my eyes, the moon was shining through the bedroom window. The house was still, the neighborhood quiet. Something beckoned me to rise, a soft tug. Nothing mystical, just a habit to the place. Lines from a poem of his came to mind:

When you wake to the dream of now

from night and its other dream,

you carry day out of the dark

like a flame.

This beckoning before first light brought a hint from my fathers life, and I accepted it:

..................................

Your life you live by the light you find

and follow it on as well as you can,

carrying through darkness wherever you go

your one little fire that will start again.

from The Dream of Now

I dressed and shuffled down the hall. In the kitchen, I remembered how my father would make a cup of instant coffee and some toast. Following his custom, I put the kettle on, sliced bread my mother had made, and marveled at how sharp my father had kept the knife. The plink of the spoon stirring coffee was the only sound, then the scrape of a butter knife. My fathers ritual pulled me on: I was to go to the couch and lie down with paper. I took the green mohair blanket from the closet, turned on a lamp, and settled in the horizontal place on the couch where my father had greeted ten thousand early mornings with his pen and paper. I put my head on the pillow just where his head had worn through the silk lining and propped my notebook against my knees.

What should I write? There was no sign, only a feeling of generosity in the room. A streetlight brightened the curtain beside me, but the rest of the room was dark. I let my gaze rove the wallsthe fireplace, the dim rectangle of a painting, the hooded box of the television cabinet, a table with magazines. It was all ordinary, at rest. In the dark of the house my fathers death had become an empty bowl that filled from below, the stone cavern of a spring. I felt grief, and also abundance. Many people had written us, Words cannot begin to express how we feel without Bill.... I, too, was sometimes mute with grief. But if my father had taught me one thing about writing, it was that words can begin to express how it is in hard times, especially if the words are relaxed, direct in their own plain ways.

I looked for a long time at the bouquet of sunflowers on the coffee table. I remembered sunflowers are the state flower of Kansas. I remembered my fathers poem about yellow cars. I remembered how we had eaten the last of his summer plantings of green beans.

I thought back to my fathers last poem, the one he wrote the day he died. He had begun with a line from an ordinary experiencea stray call from an insurance agent trying to track down what turned out to be a different William Stafford. The call had amused him, the agents words had stayed with him. And that morning, 28 August 1993, he had begun to write:

Are you Mr. William Stafford?

Yes, but....

As he often did, he started his last poem with recent news from his own life before coming to deeper things. But I wasnt delving into his writing now. I was in the cell of his writing time, alive earlier than anyone, more alert in welcome, listening.

The house was so quiet I heard the tap of my heart, felt the sweetness of each breath and the easy exhalation. It seemed my eyes, as in one of my fathers poems, had been tapered for braille. The edge of the coffee table held a soft gleam from the streetlight. The stack of magazines was jostled where he had touched them. Then I saw how each sunflower had dropped a little constellation of pollen on the table. The pollen seemed to burn. The soft tug that had wakened me, the tug I still felt, wanted me awake to ordinary things, to sip my bitter coffee, to gaze about, and to wait. Another of his poems came to mind: