First and greatest honor goes to my brother, Bret, for his example and long companionship in the busy mysteries of this life. I thank you, I listen to you, I learn from you, I reach out to you.

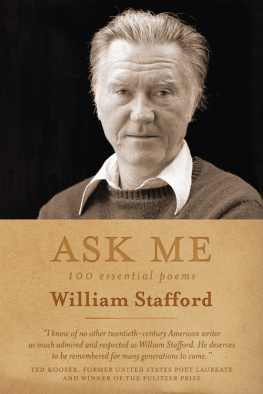

As our fathers literary executor, I have direct access to the writings, both public and private, of William Stafford. I am grateful to Doug Erickson, Jeremy Skinner, and Paul Merchant at the William Stafford Archives, Lewis & Clark College, for their ongoing care with these materials, and generous help when requested.

Our mother, Dorothy Hope Stafford, has wondered with me about Brets amazing life. Likewise my sisters, when they were able, despite deep and continuing grief, have helped me venture into our heritage in order to tell my part.

I thank my niece and nephew, Katie and Matthew Massett Stafford, for putting up with me when I talk and talk a

bout their father. My opportunity now is to welcome them into my life on their own amazing terms.

I would like to thank my students at the Northwest Writing Institute and elsewhere for their acts of witness over many years, by writing about difficult subjects, and their encouragement to me to enter my own difficult realms with a ready pen. I have quoted several of these students in this book and learned courage and ways to adventure in the art of story from many, many others.

Friends from all over have accompanied me for years in puzzling over the memories and questions that form this book. Thanks to all who listened, counseled, and befriended who I am trying to be. And thanks to those who offered particular stories and insights that have helped me see my brother in new ways.

Many people helped me write this book, and some others will tell me I have it wrong. Im sure I do in some respectsmisdirected in emphasis, sometimes wrong in fact. What I set out to do is fill a silence and start a conversation. I welcome correction, but even more I welcome many voices telling their own stories of my brother and of these important matters: passion, pacifism, silence.

I offer my deepest gratitude to my wife, Perrin, and our son, Guthrie, and my daughter, Rosemary, for their unfailing encouragement in this writing project. They have helped me stay the course and find the time to make this book, keeping faith with the notion in our wedding vows to turn silence into words.

I would like to thank Kathleen Holt at Oregon Humanities Magazine for permission to reprint, in slightly different form, the essay Rsum of Failures. Also thanks to the editors of the Lewis & Clark Chronicle, who published an earlier version of Talking Recklessly. I would like to thank the Geography Department at Oregon State University and the library staffs at the University of Victoria and at the University of Oregon for permission to reprint passages from my brothers papers there.

And great good thanks to Barbara Ras, my friend and editor at Trinity University Press, who responded to my first mention of this project with the kind of welcome that made me finally begin to write.

No one but me is responsible for what I have writtenright or wrong, saintly or sinful, revealing or resistantfor I am still resistant, often, despite all I can do, to reveal hard things. This is my story of my brother. I believe he has found some peace. And so have I.

KIM STAFFORD has taught since 1979 at Lewis and Clark College, where he is the founding director of the Northwest Writing Institute and co-director of the Documentary Studies program. He also serves as the literary executor for the estate of William Stafford. He has worked as an oral historian, letterpress printer, editor, photographer, teacher, and visiting writer in communities and at colleges across the country, and in Italy and Bhutan.

Stafford has published a dozen books of poetry and prose, including The Muses among Us: Eloquent Listening and Other Pleasures of the Writers Craft; Early Morning: Remembering My Father, William Stafford; and Having Everything Right: Essays of Place. He has received two National Endowment for the Arts creative writing fellowships, the Oregon Governors Arts Award, and a Western States Book Award. He lives in Portland, Oregon, with his wife and children.

This is a book of questions, a beginningnot a last word, or an end. In spite of everything I can remember or try to puzzle out, my brother will remain a mystery, and his final act an enigma. But there is a consoling optical effect with memory: when certain events get far, they gain focus. Over time, I can see with greater clarity my relation with my brother, who took his life with a gun, and my fathers relation with his brother, who took his life with alcohol. I see my brothers children; I see my uncles children. And there is no simple thing to say. The relation looms forth between my brothers inner life and his outer behavior, between my own silences and my writing. Over time, events become memories, and memories become stories, and in the process we may learn the trick to understand. For it is a trick; it doesnt just happen.

As the old saying goes, life is lived forward but understood backward. If only I had known... is a futile cry. You dont know until you do, and that takes timebut not marking time. It takes time interrogating silence, facing down darkness, seeking truth. The telling in this book had to be capricious in time, for often former things illuminate later things, but sometimes the present clarifies the pastlike sunlight stepping through a forest from east to west, but also glancing back to brighten hidden things that were shadowed at dawn.

Home ground is my brothers ground, and these places keep teaching me: Hood River, Salem, Mount Adams, Eugene, Strawberry Mountainwherever I go, my brothers places shimmer in their own strange light. My soul has pockets, and into these pockets gather the places and moments that mutter my brothers life, and from this muttering, if I can attend, some clarity may come. He was to have been my guide, the older one, wise counselor. In place of him, his story may be my compass. Like a navigator on the open sea, I have to triangulate with the tools I have: my memory of him, my own life episodes that feel in keeping with his story, and what I am learning with my second wife, Perrin, and our son.

Some of the stories in this book I have told before. The mystery of telling stories from memory, I find, is that they keep revealing new dimensions. The perennial story called You Cant Eat Beauty, for example, here is a matter of life and death. And the story of my fathers assessment of my brother as a saint here carries a dark twist.

As E. O. Wilson says, the honeybees, when they dance, tell each other the oldest story of all: I want to show you where I found some food. This, too, is my goalto look back into early times in my familys life, a time flickering with shadows and honey, in order to locate there what will feed us now.

When I began to write this book, I recognized the sheer volume of my memories of my brotherstory after story thronged to mind. At the same time, I recognized the uncertainty of memorydetail after detail I could not remember, or might remember wrong. My question at the outset: What can I trust about memory?

As I began to write, though, I also recognized that the recollections I do have of my brother, of my family, and of the historical period spanned by this bookthese memories are filled with episodes of severe reticence, denial, and suppression. Painful acts like suicide, and mysterious life dimensions like depression, tend to call forth both indelible memories and a velvet cloak of silence.

As a passage out of silence, memory is the chrysalis of the invisible: a plodding fact goes into the mind, you dither and ponder and dream and write, and a story with rudimentary wings may struggle forth. Memory is an event-based sermon to the self, rooted in secular fact, but wicking the water of spirit up from hiding. The factual details of memory alone may be suspect, but the meanings they sift from the forgottenthese may be the gold we carry still when our treasure is gone. Where sorrow came like a wheeled vessel, and took my brother away (violence, blood, silence), memory and this telling bring him partway back.