FOLLOWING THE EQUATOR

A JOURNEY AROUND THE WORLD

BY

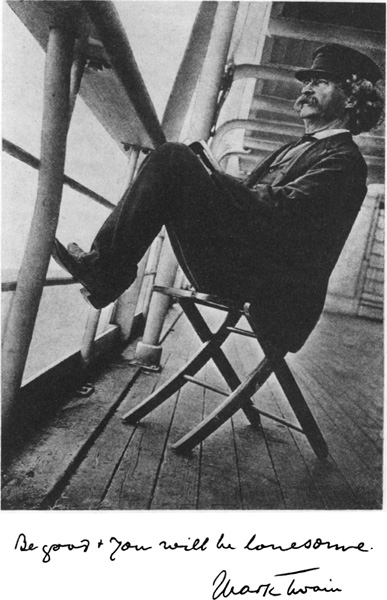

MARK TWAIN

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

NEW YORK

This Dover edition, first published in 1989, is an unabridged and unaltered republication of the work originally published in 1897 by The American Publishing Company, Hartford, Connecticut.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y 11501

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Twain, Mark, 1835-1910.

Following the equator: a journey around the world / Mark Twain.

p. cm.

Reprint. Originally published: Hartford, Conn.: American Pub. Co., 1897.

eISBN 13: 978-0-486-12354-7

1. Twain, Mark, 1835-1910. 2. Voyages around the world. I. Title.

G440.T95T93 1989 |

910.4 1dc20 | 89-33693 |

CIP |

THIS BOOK

MY YOUNG FRIEND

HARRY ROGERS,

WITH RECOGNITION

OF WHAT HE IS, AND APPREHENSION OF WHAT HE MAY BECOME

UNLESS HE FORM HIMSELF A LITTLE MORE CLOSELY

UPON THE MODEL OF

THE AUTHOR.

THE PUDDN HEAD MAXIMS.

THESE WISDOMS ARE FOR THE LURING OF YOUTH TOWARD

HIGH MORAL ALTITUDES. THE AUTHOR DID NOT

GATHER THEM FROM PRACTICE, BUT FROM

OBSERVATION. TO BE GOOD IS NOBLE;

BUT TO SHOW OTHERS HOW

TO BE GOOD IS NOBLER

AND NO TROUBLE.

Dan Beard, A. B. Frost, B. W. Cinedinst, Frederick Dielman, Peter Newell, F. M. Seinor, T. J. Fogarty, C. H. Warren, A. G. Reinhart, F. Berkeley Smith, C. Allan Gilbert.

The publishers acknowledge the courtesy extended by Walter G. Chase, Boston, Major J. B. Pond, New York, and F. R. Reynolds, Manchester, England, in furnishing many of the photographs reproduced in this volume.

THEY PASSED IN REVIEW.

CHAPTER I.

A man may have no had habits and have worse.

Puddnhead Wilsons New Calendar.

T HE starting point of this lecturing-trip around the world was Paris, where we had been living a year or two.

We sailed for America, and there made certain preparations. This took but little time. Two members of my family elected to go with me. Also a carbuncle. The dictionary says a carbuncle is a kind of jewel. Humor is out of place in a dictionary.

We started westward from New York in midsummer, with Major Pond to manage the platform-business as far as the Pacific. It was warm work, all the way, and the last fortnight of it was suffocatingly smoky, for in Oregon and British Columbia the forest fires were raging. We had an added week of smoke at the seaboard, where we were obliged to wait awhile for our ship. She had been getting herself ashore in the smoke, and she had to be docked and repaired. We sailed at last; and so ended a snail-paced march across the continent, which had lasted forty days.

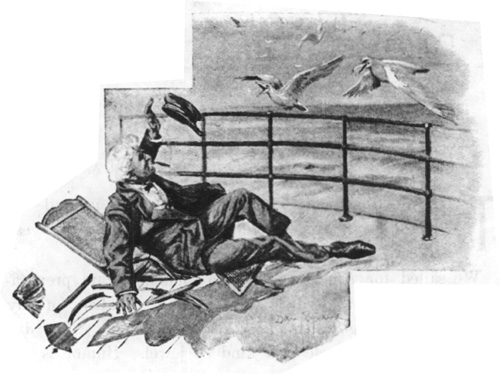

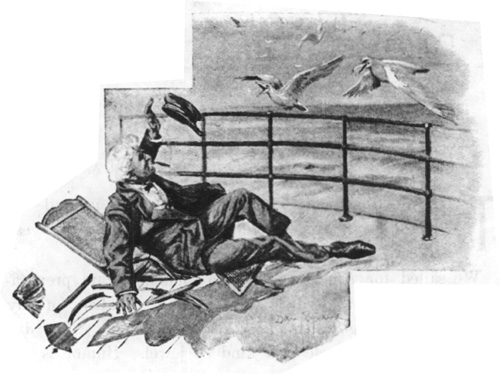

We moved westward about mid-afternoon over a rippled and sparkling summer sea; an enticing sea, a clean and cool sea, and apparently a welcome sea to all on board; it certainly was to me, after the distressful dustings and smokings and swelterings of the past weeks. The voyage would furnish a three-weeks holiday, with hardly a break in it. We had the whole Pacific Ocean in front of us, with nothing to do but do nothing and be comfortable. The city of Victoria was twinkling dim in the deep heart of her smoke-cloud, and getting ready to vanish; and now we closed the field-glasses and sat down on our steamer chairs contented and at peace. But they went to wreck and ruin under us and brought us to shame before all the passengers. They had been furnished by the largest furniture-dealing house in Victoria, and were worth a couple of farthings a dozen, though they had cost us the price of honest chairs. In the Pacific and Indian Oceans one must still bring his own deck-chair on board or go without, just as in the old forgotten Atlantic timesthose Dark Ages of sea travel.

EVEN THE GULLS SMILED.

Ours was a reasonably comfortable ship, with the customary sea-going fareplenty of good food furnished by the Deity and cooked by the devil. The discipline observable on board was perhaps as good as it is anywhere in the Pacific and Indian Oceans. The ship was not very well arranged for tropical service; but that is nothing, for this is the rule for ships which ply in the tropics. She had an over-supply of cock-roaches, but this is also the rule with ships doing business in the summer seasat least such as have been long in service. Our young captain was a very handsome man, tall and perfectly formed, the very figure to show up a smart uniforms finest effects. He was a man of the best intentions, and was polite and courteous even to courtliness. There was a soft grace and finish about his manners which made whatever place he happened to be in seem for the moment a drawing-room. He avoided the smoking-room. He had no vices. He did not smoke or chew tobacco or take snuff; he did not swear, or use slang, or rude, or coarse, or indelicate language, or make puns, or tell anecdotes, or laugh intemperately, or raise his voice above the moderate pitch enjoined by the canons of good form. When he gave an order, his manner modified it into a request. After dinner he and his officers joined the ladies and gentlemen in the ladies saloon, and shared in the singing and piano playing, and helped turn the music. He had a sweet and sympathetic tenor voice, and used it with taste and effect. After the music he played whist there, always with the same partner and opponents, until the ladies bedtime. The electric lights burned there as late as the ladies and their friends might desire, but they were not allowed to burn in the smoking-room after eleven. There were many laws on the ships statute book, of course; but so far as I could see, this and one other were the only ones that were rigidly enforced. The captain explained that he enforced this one because his own cabin adjoined the smoking-room, and the smell of tobacco smoke made him sick. I did not see how our smoke could reach him, for the smoking-room and his cabin were on the upper deck, targets for all the winds that blew; and besides there was no crack of communication between them, no opening of any sort in the solid intervening bulkhead. Still, to a delicate stomach even imaginary smoke can convey damage.

The captain, with his gentle nature, his polish, his sweetness, his moral and verbal purity, seemed pathetically out of place in his rude and autocratic vocation. It seemed another instance of the irony of fate.