For Kay Weidensaul

Text copyright 2016 Scott Weidensaul

Photographs, maps, and artwork copyright 1994 Scott Weidensaul

Cover photograph: Dfikar/Dreamstime.com

Author photo: Amiran White

First Fulcrum trade paperback edition August 2000.

Twentieth anniversary edition 2016.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

The author would like to thank Oxford University Press for permission to reprint excerpts

from On a Monument to the Pigeon, in A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold. Copyright 1949 Aldo Leopold. Used by per mission of Oxford University Press. The excerpt from

The Graenlendinga Saga in The Vinland Sagas, translated by Magnus Magnusson and

Hermann Plsson, copyright 1965 by Magnus Magnusson and Hermann Piilsson, is reprinted by permission of Penguin Books.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Weidensaul, Scott.

Title: Mountains of the heart : a natural history of the Appalachians.

Description: 20th anniversary edition. | Golden, CO : Fulcrum Publishing,

2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015039448 | ISBN 9781938486883

Subjects: LCSH: Natural history--Appalachian Mountains. | Appalachian

Mountains. | Nature--Effect of human beings on--Appalachian Mountains.

Classification: LCC QH104.5.A6 W45 2016 | DDC 508.74--dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015039448

Printed in the United States

0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Fulcrum Publishing

4690 Table Mountain Parkway, Suite 100

Golden, Colorado 80403

800-992-2908 303-277-1623

www.fulcrum-books.com

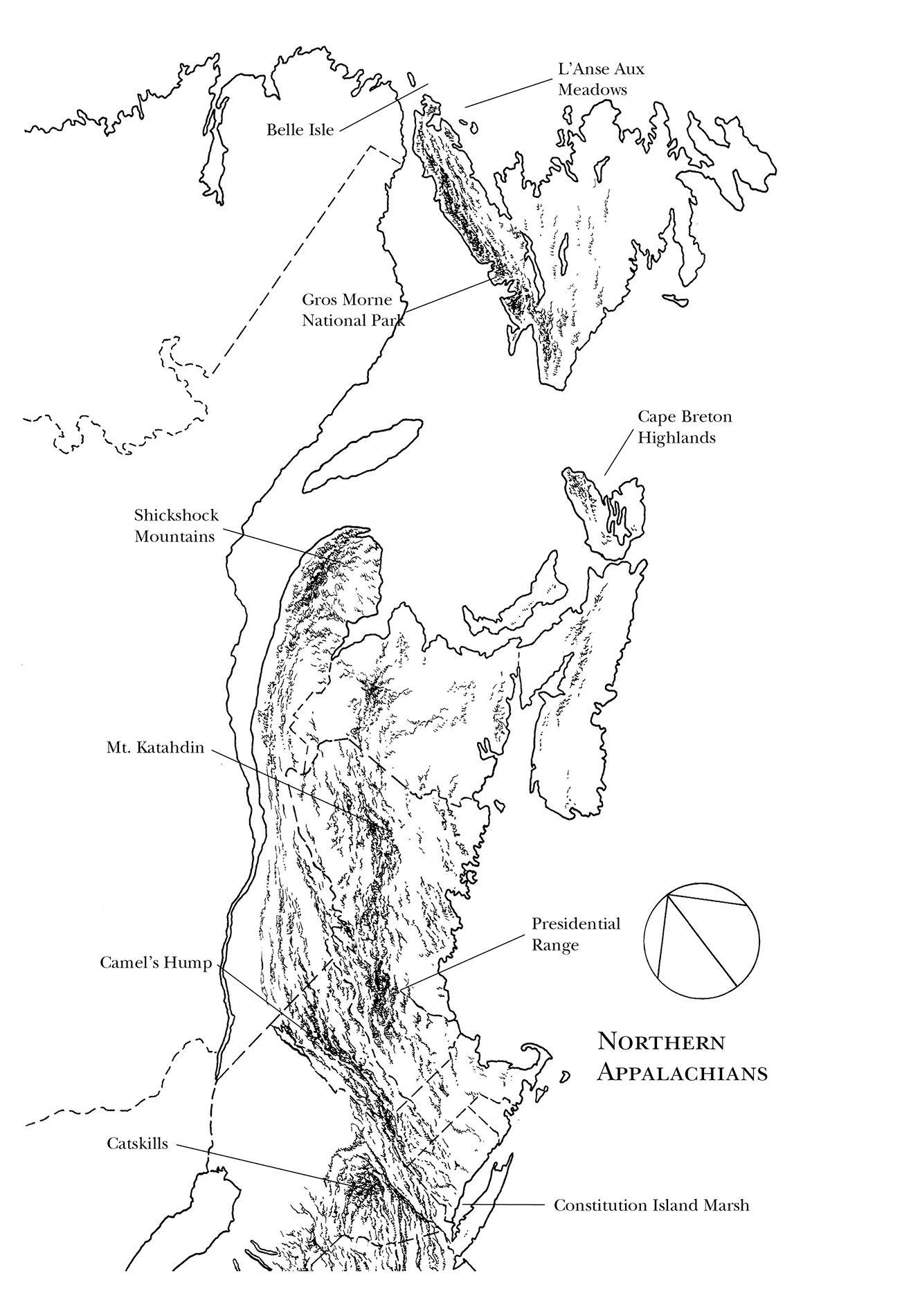

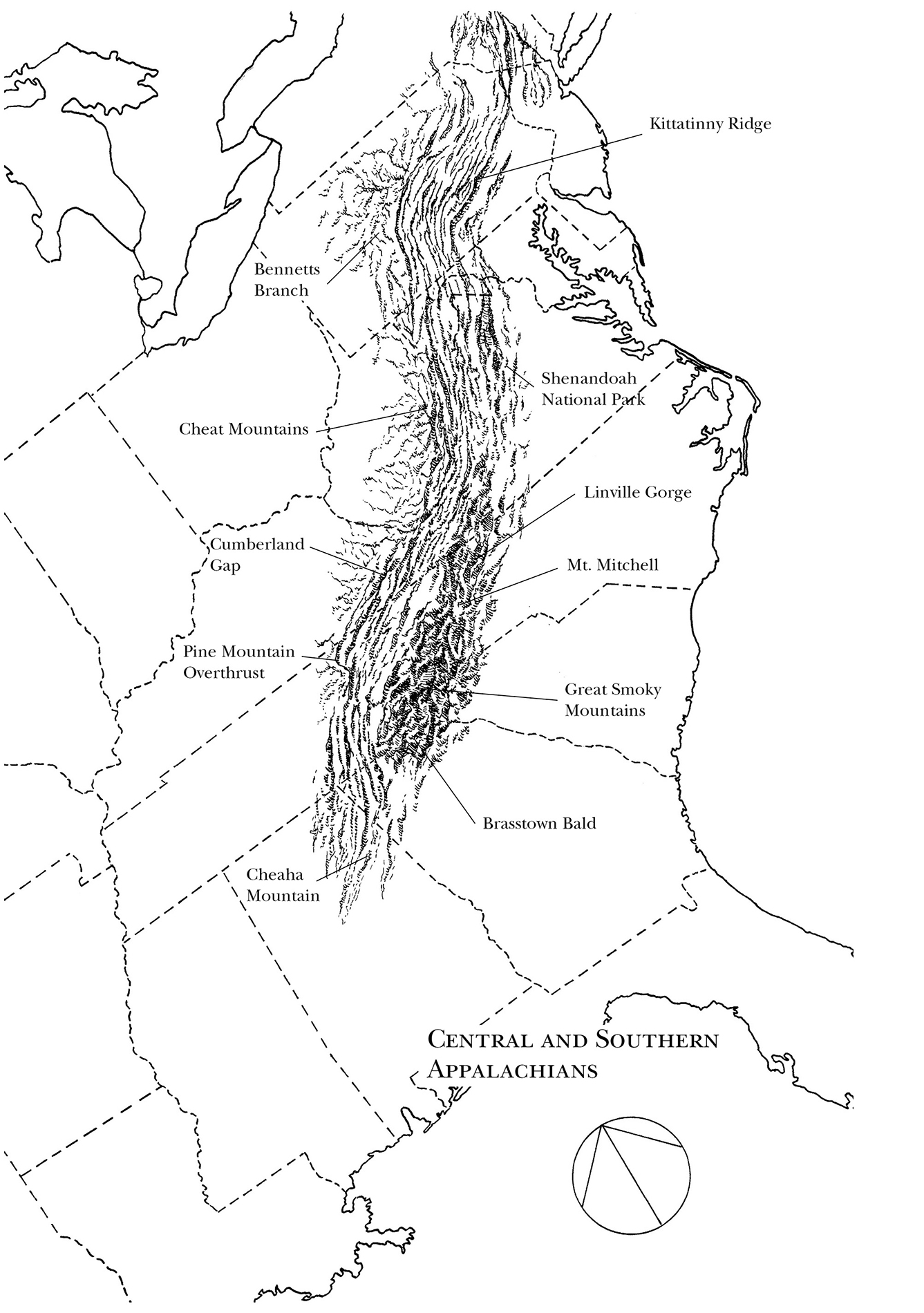

Geographic Provinces

of the Appalachians

Morning fog lifts in Cades Cove, in Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Preface to the

Twentieth Anniversary

Edition

To a human, twenty years is a long time. It represents the span from infancy to adulthoodand for some, the shift from robust middle age to a retirement home (or even to the grave).

Not so with mountains. Time wears slowly on them, especially an ancient range like the Appalachians, whose history stretches back nearly 500 million years. For a system whose roots reach to before the dawn of modern fishes, and which rose skyward when the ancestors of dinosaurs and mammals were still diverging, twenty years is a comically short period. Compared with 500 million years, it barely counts as an eyeblinka mere 0.000004 percent. If the history of the Appalachians encompassed a year, those twenty years would represent the final 1.26 seconds.

Yet we are fleeting, ephemeral humans, and we mark our anniversaries. Its been twenty years since Mountains of the Heart was first published, and if that is a tiny tick on the geologic clock, its not without its significance. The two decades since this book was first published have brought many changes to these venerable hills, all of them wrought, to one degree or another, by the busy, bustling people that now inhabit every corner of the Appalachian landscapeand by many who live far away from it as well.

The publication of a fresh edition gives an author a chance to revisit a subject, if he chooses. There is a tension between preserving the flavor of the original work, which is a product of a particular time, place and mindset, but which may now be outdated or simply incorrect. Thats an especially tricky balancing act for a book such as this that depends so heavily on first-person narrative. Consequently, I have tried to bring Mountains of the Heart into the twenty-first century with a light hand. Most remains as it was written in 1994, partly because so much of it deals with timeless subjects untouched by the passage of a few decades.

But the mountains have not themselves been untouched by the passage of twenty years. To hills that suffered so much in the past, from mining and timbering, abuse and pollution, there are new threats. Extractive industries have long had their way with these ridges and valleys (and with the people who inhabit them), but neverto choose one of the most egregious exampleson such a landscape-altering scale as the mining technique known as mountaintop removal.

Its difficult for anyone who hasnt seen a mountaintop removal operation to really appreciate the scale of the destructionand because most of it occurs in poor regions far off the tourist track, most Americans never do witness it. The name sums up the devastation: With explosives and immense equipment, the upper third or more of a mountainsometimes as much as eight hundred feet of ridgeis blasted to rubble. This overburden, which hides the thin seam of coal, is pushed into the neighboring valley, engulfing forests, entombing streams and burying homesteads that have been there for centuries. The streams now buried beneath the overburden seep out, full of toxins like selenium that leach from the smashed debris, ruining those waterways downstream that escaped direct destruction.

The result is a vast, flat wasteland of a plateau, sometimes up to fifteen square miles in size, bearing little but rough grass, where a rich Appalachian forest (and tight-knit Appalachian communities) once stood. By 2012, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimated some 2,200 square milesan area roughly the size of Delawarehad been destroyed by mountaintop removal, including two thousand miles of streams. The litany of environmental and health ills stemming from mountaintop removal is long and depressingand extraordinarily well documented, which makes the decades-long struggle against mountaintop removal especially frustrating, despite some belated federal restrictions.

More recently, a wholly new energy boom has emerged in parts of the Appalachians in the form of shale gas extraction, especially in the Marcellus Formation underlying New York, Pennsylvania and West Virginia. New drilling techniques are providing access to gas trapped up to eight thousand feet below ground, in particular the approach known as hydraulic fracturing, or fracking. In fracking, water, sand, salts and a witches brew of hundreds of chemicals are pumped down under extreme pressure, fracturing the rock strata and freeing tiny bubbles of natural gasrevolutionizing gas extraction and bringing industrial energy production to regions that were just a few years ago quiet rural counties. Fracking has sparked enormous conflict, pitting neighbors against neighbors, local municipalities against states, and prompting concerns about the potentially devastating ecological problems associated with it.

Overlay a map of the Marcellus Formation with a map of Pennsylvania, and the correspondence between where the gas is most readily accessible, and the wildest, emptiest parts of the statenotably the Appalachian High Plateau country of the states northern tieris instantly apparent. That makes the impact of the drilling boom, and the reckless way in which it has often been managed, even more painful for a conservationist.