For Helen

Time and change shall not avail

to break the friendships formed

O, my loves like a red, red rose,

thats newly sprung in June;

O, my loves like the melody

thats sweetly playd in tune.

As fair art thou, my bonnie lass,

so deep in love am I,

and I will love thee still, my dear,

till a the seas gang dry.

Till a the seas gang dry, my dear,

and the rocks melt wi the sun:

I will love thee still, my dear,

while the sands o life shall run.

And fare thee well, my only love!

And fare thee well awhile!

And I will come again, my love,

tho it were ten thousand mile.

Robert Burns, A Red, Red Rose

WHAT HAPPENED

15TH28TH JUNE 1938

Youre a brave lassie.

Thats what my grandfather told me as he gave me his shotgun.

Stand fast and guard me, he instructed. If this fellow tries to fight, you give him another dose.

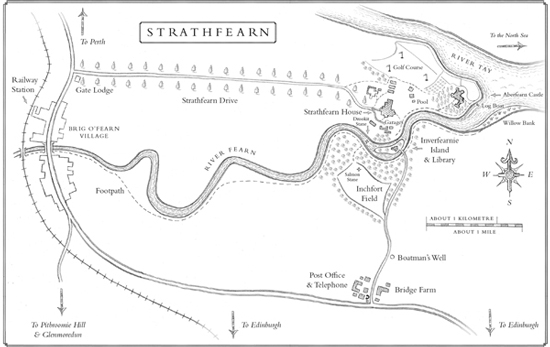

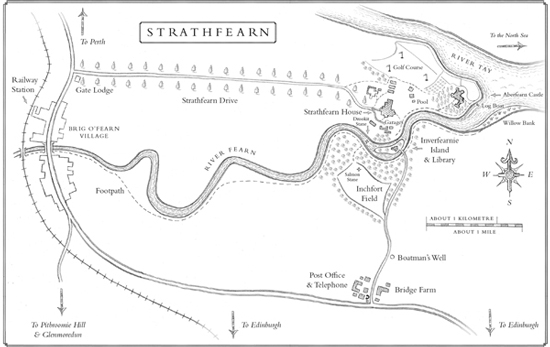

Grandad turned back to the moaning man hed just wounded. The villain was lying half-sunk in the mud on the edge of the riverbank, clutching his leg where a cartridge-ful of lead pellets had emptied into his thigh. It was a late summer evening, my last with Grandad before I went off to boarding school for the first time, and wed not expected to shoot anything bigger than a rabbit. But here I was aiming a shotgun at a living man while Grandad waded into the burn, which is what we called the River Fearn where it flowed through his estate, so he could tie the evildoers hands behind his back with the strap of his shotgun.

Rape a burn, would you! Grandad railed at him while he worked. Ive never seen the like! Youve destroyed that shell bed completely. Two hundred river mussels round about, piled there like a midden heap! And youve not found a single pearl, have you? Because you dont know a pearl mussel from your own backside! Youre like a bank robber thats never cracked a safe or seen a banknote!

It was true the man had torn through dozens of river mussels, methodically splitting the shells open one by one in the hope of finding a rare and beautiful Scottish river pearl. The flat rock at the edge of the riverbank was littered with the broken and dying remains.

Grandads shotgun was almost too heavy for me to hold steady. I kept it jammed against my shoulder with increasingly aching arms. I swear by my glorious ancestors, that man was twice Grandads size. Of course Grandad was not a very big man none of us Murrays is very big. And he was in his seventies, even though he wasnt yet ill. The villain had a pistol hed dropped it when hed been hurt, but it wasnt out of reach. Without me there to guard Grandad as he bound the other man, they might have ended up in a duel. Brave! I felt like William Wallace, Guardian of Scotland.

The wounded man was both pathetic and vengeful. Ill see you in Sheriff Court, he told my grandfather, whining and groaning. Im not after salmon and theres no law against pearl fishing, but its illegal to shoot a man.

Grandad wasnt scared. This is a private river.

Those tinker folk take pearls here all the time. They come in their tents and bide a week like gypsies, and go away with their pockets full!

No tinker I know would ever rape a burn like this! And theyve the decency to ask permission on my private land! Theres laws and laws. Respect for a river and its creatures goes unwritten. And the written law says that I can haul you in for poaching on my beat, whether its salmon or pearls or anything else.

I didnt I wasnae

Whisht. Never mind what you were doing in the water: you pointed your own gun at my wee granddaughter. Grandad now confiscated the pistol that was lying in the mud, and tucked it into his willow-weave fishermans creel. Thats excuse enough for me. Im the Earl of Strathfearn. Whose word will the law take, laddie, yours or mine?

Grandad owned all of Strathfearn then, and the salmon and trout fishing rights that went with it. It was a perfect little Scottish estate, with a ruined castle and a baronial manor, nestled in woodland just where the River Fearn meets the River Tay. Its true its not illegal for anyone to fish for pearls there, but its still private land. You cant just wade in and destroy someone elses river. I remember how shocking Grandads accusation sounded: Rape a burn, would you!

Was that only three years ago? It feels like Grandad was ill for twice that long. And now hes been dead for months. And the estate was sold and changed hands even while my poor grandmother was still living in it. Grandad was so alive then. Wed worked together.

Steady, lass, hed said, seeing my arms trembling. I held on while Grandad dragged the unfortunate mussel-bed destroyer to his feet and helped him out of the burn and on to the riverbank, trailing forget-me-nots and muck and blood. I flinched out of his way in distaste.

Hed aimed a pistol at me earlier. Id been ahead of Grandad on the river path and the strange man had snarled at me, One step closer and youre asking for trouble. Id hesitated, not wanting to turn my back on his gun. But Grandad had taken the law into his own hands and fired first.

Now, as the bound, bleeding prisoner struggled past me so he could pull himself over to the flat rock and rest amid the broken mussel shells, our eyes met for a moment in mutual hatred. I wondered if he really would have shot at me.

Now see here, Grandad lectured him, getting out his hip flask and allowing the wounded man to take a taste of the Water of Life. See the chimneys rising above the birches at the rivers bend? Thats the County Councils old library on Inverfearnie Island, and theres a telephone there. You and I are going to wait here while the lassie goes to ring the police. He turned to me. Julie, tell them to send the Water Bailiff out here. Hes the one to deal with a poacher. And then I want you to stay there with the librarian until I come and fetch you. Her name is Mary Kinnaird.

I gave an internal sigh of relief not a visible one, because being called brave by my grandad was the highest praise Id ever aspired to, but relief nevertheless. Ringing the police from the Inverfearnie Library was a mission I felt much more capable of completing than shooting a trespasser. I gave Grandad back his shotgun ceremoniously. Then I sprinted for the library, stung by nettles on the river path and streaking my shins with mud. I skidded over the mossy stones on the humpbacked bridge that connects Inverfearnie Island to the east bank of the Fearn, and came to a breathless halt before the stout oak door of the seventeenth-century library building, churning up the gravel of the drive with my canvas shoes as if I were the messenger at the Battle of Marathon.

It was past six and the library was closed. I knew that Mary Kinnaird, the new librarian and custodian who lived there all alone, had only just finished university, but Id never met her, and it certainly never occurred to me that she wouldnt be able to hear the bell. When nobody came, not even after I gave a series of pounding kicks to the door, I decided the situation was desperate enough to warrant breaking in and climbing through a window. They were casement windows that opened outward if I broke a pane near a latch it would be easy to get in. I snatched up a handful of stones from the gravel drive and hurled them hard at one of the leaded windowpanes nearest the ground. The glass smashed explosively, and I could hear the rocks hitting the floor inside like hailstones.

Next page