Cover copyright 2017 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers is an imprint of Hachette Books, a division of Hachette Book Group. The Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Additional photo credits information is .

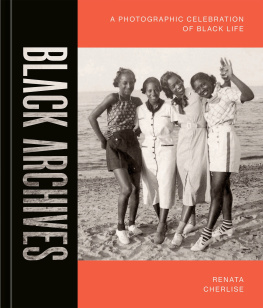

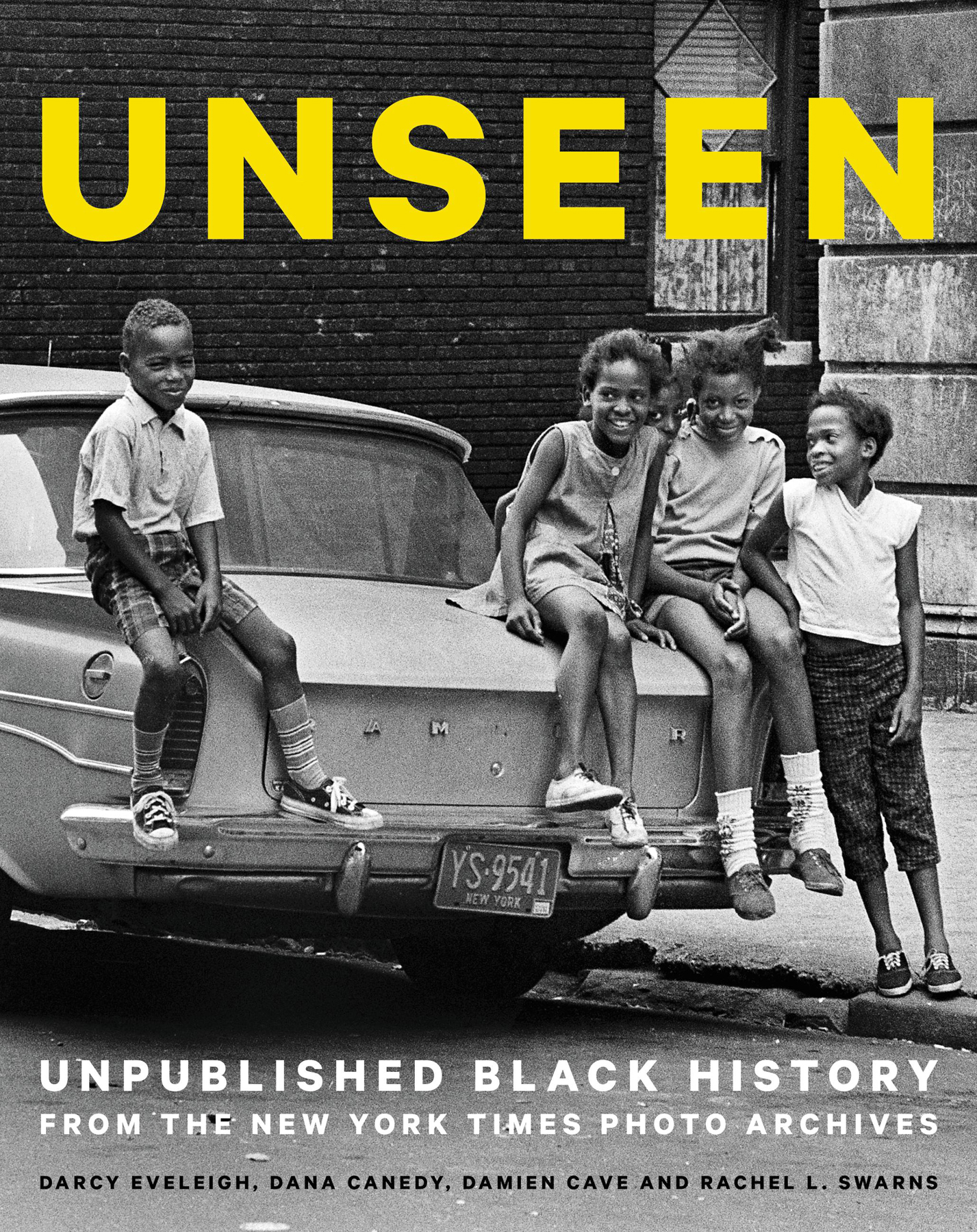

E ach photograph on these pages will take you back: To the charred wreckage of Malcolm Xs house in Queens, just hours after it was bombed. To a packed church in Greenwood, Mississippi, where Medgar Evers inspired African-Americans to dream of a day when their votes would count. To Lena Hornes elegant penthouse on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. To a city sidewalk where schoolgirls jumped rope, while the writer Zora Neale Hurston cheered them on, behind the scenes.

These stunning images from black history, drawn from old negatives, have long been buried in the musty envelopes and crowded bins of The New York Times archives. Unseen and unpublished for decades, they are gathered together in this rare collection for the very first time.

Our photographers for The Times captured these scenes, and many, many more. They snapped pictures of pioneers in Hollywood and hip-hop and sports; prominent figures, such as James Baldwin, Thurgood Marshall and the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.; and ordinary people, savoring the joys of everyday life.

They illuminate stories that were never told in the newspaper and others that have been mostly forgotten. Yet as you look at these images and read the stories behind them, you may find yourself wondering, as we did: How did they languish unseen for so long?

Were the photographsor the people in themnot deemed newsworthy enough? Did they not arrive in time for publication? Were they pushed aside by words at an institution long known as the Gray Lady, or by the biases of editors, whether intentional or unintentional?

The reality is that all these factors probably contributed.

As journalists, we strive for objectivity and impartiality as we question and portray the world around us. Yet we rarely turn the lens on ourselves. At a time when concerns about the persistence of the racial divide simmer across the country, it is worth considering how we as an institution have depicted African-Americans in our pages and, at times, erased them from view.

The New York Times is known today as a leader in photography, with a team of staffers and freelancers who bring vivid pictures to our readers from war zones in Afghanistan and the Middle East, elementary schools in Harlem and county fairs during hotly contested presidential campaigns. The newspaper has won nine Pulitzer Prizes for photography, seven of them in the 2000s.

But we have not always valued images so highly.

For most of the twentieth century, The Times had only a small staff of photographersthe first was hired sometime after 1910and nearly all of them were based in New York City. As a result, most staff photographs depicted local events, though The Times also bought pictures from freelancers and studios in other parts of the country and overseas. (The Timess picture agency, Wide World News Photo Service, which had staff members in London, Berlin and elsewhere, was sold to The Associated Press in 1941.)

In those early days, we put a premium on words, not pictures, which meant that many photographs that were taken were never published.

Its likely, however, that some holes in coverage reflected the biases of some editors at The Times, which has long been known as the newspaper of record, who determined what was newsworthy and what was not, at a time when black people were marginalized in society and in the media.

HOW DID THESE PHOTOGRAPHS LANGUISH UNSEEN FOR SO LONG?

After months of searching through our archives, we could not find a single staff photograph of the scholar W.E.B. Du Bois or Romare Bearden, one of the countrys pre-eminent artists, or of Richard Wright, the influential author of Native Son and Black Boy. (The Times did publish a handful of photographs of these men taken by freelancers, friends or private studios.)

Sarah Lewis, an assistant professor of History of Art, Architecture and African-American studies at Harvard University, said this is no surprise, given the nations long history of demeaning and ignoring the visual narratives of black people.

In the nineteenth century, when photography was born, scientists used photographs to support racist theories of white superiority. The camera became an instrument of denigration, Lewis said, as pictures of slaves were taken to try to prove that blacks were a separate and subhuman species.

At the same time, though, black photographers were using their cameras to depict what the white world so often failed to see: the beauty in their communities. Frederick Douglass and Du Bois believed that African-Americans could harness the power of the new technology to capture the dignity and accomplishments of black people and document events that would otherwise go unrecorded.

Douglass, the runaway slave, abolitionist and statesman, argued that the moral and social influence of pictures was even more important in shaping national culture than the making of its laws.

Pointedly challenging the notion of black inferiority, Du Bois displayed photographs of black businessmen, craftsmen, homeowners, clergymen, university students, musicians, laborers and well-dressed men, women and children of all hues at the Paris Exposition in 1900. He noted that the Negro faces he presented at that world fair hardly square with conventional American ideas.

It was important to create a new vision, said Deborah Willis, who chairs the Department of Photography and Imaging at New York Universitys Tisch School of the Arts, of Du Boiss efforts.