Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thank you, God, for making a way.

Infinite gratitude to my maternal bloodline, those named and unnamed, including: Theresa, Corrine, Estellar, Cora, and Brenda. To my mom, Patricia, and my dad, Edwin, for lending their everlasting love and support through this realm and through the next. My partner, Gene, and our daughter, Geanna. Sylvia, Dominique, Dante, Ronsonet, Carla, Chauncey, Markale, Gilbert, Regene, Alexis, Malachi, Lauren, Mercy, Lisa, Myka, and Steven.

To my editors, Kaitlin Ketchum and Nicole Counts: your guidance and infinite wisdom have been lifesavers while embarking on one of the biggest projects of my life. Thank you for helping our familys legacy to live on. Thank you to designer Annie Marino, production manager Serena Sigona, production editors Ann Spradlin and Ashley Pierce, marketer Monica Stanton, and publicist Felix Cruz at Ten Speed Press.

Thank you to my village. Thank you to my community. Thank you to all who share my work and keep the work lifted in rooms and conversations.

Thanks also to Titus, Lutish, Eddie, Damion, Dominique, Randall, Damion II, Chauncey II, Chauncey III, Chaunacey, Leoniquia, Chelsey, Royce, TaNyha, Yazmiyn, Braylen, Ziodonee, Deondre, Airyanna, Zayden, Kathy, Raymond, Wesley, Zoey, Nico, Theodore, Sadie, Juvada, Anita, Jakki, Kenneth, Timothy, Ms. Pamela, and Ms. Lorraine.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Renata Cherlise is a multidisciplinary, research-based visual artist and memory worker who uses various mediums to explore themes of identity and familial interiors within Black communities.

Born and raised in Jacksonville, Florida, Cherlises projects bridge her southern upbringing with contemporary methodologies in digital spaces while reimagining themes in literature, history, and photography to render new perspectives of the Black experience. These ideas became the foundation for Black Archives, a multimedia platform founded by Cherlise in 2015 that spotlights the Black experience and incorporates archival imagery and histories through visual explorations of a Black past, present, and future. Going beyond the norm, Black Archives examines the nuance of Black life, from the alive and ever-vibrant to the everyday and iconic, providing insight and inspiration to those seeking to understand the legacies that preceded their own.

See more of Black Archives at www.blackarchives.co or @blackarchives.co on social media.

PHOTO CREDITS

INSTITUTIONAL ARCHIVES

African American Museum & Library at Oakland, E. F. Joseph Photograph Collection: .

FAMILY ARCHIVE SUBMISSIONS

Alesha Morgan: .

HANDWRITTEN

STORIES

While documents such as census records, birth certificates, yearbooks, and newspapers can offer vital information to help reconstruct or assist with piecing together a familys story or timeline, photos offer an intimate experience and connection. One of the greatest treasures often found in family photo albums are the handwritten accountsdates, names, notesthat are folded within the pages, or written on top or on the back of photos. These stories help shorten the bridge between the living and the transitioned, the present and the past. Handwritten notes are gifts to and from ourselves, and to future generations.

We often rely on our memory and imagination to help us piece together (or create alternatives to) the many stories found within our familial lineage. Ive learned that photographs carry the answers to questions that we have, even if extracting the metadata we wantlike names, dates, and locationsis still a challenge. There are photos within my own family album that I can only wonder aboutbut it is in that wondering, that meditating on what is shown, that I come away with a deeper connection to my family. My mother is the matriarch; now in her sixties, she is the oldest living family member who can help us name faces and attach stories. It is my familys goal to name as many names as we possibly can. The living archive within my mothers body is all we have to reconstruct and share our legacy.

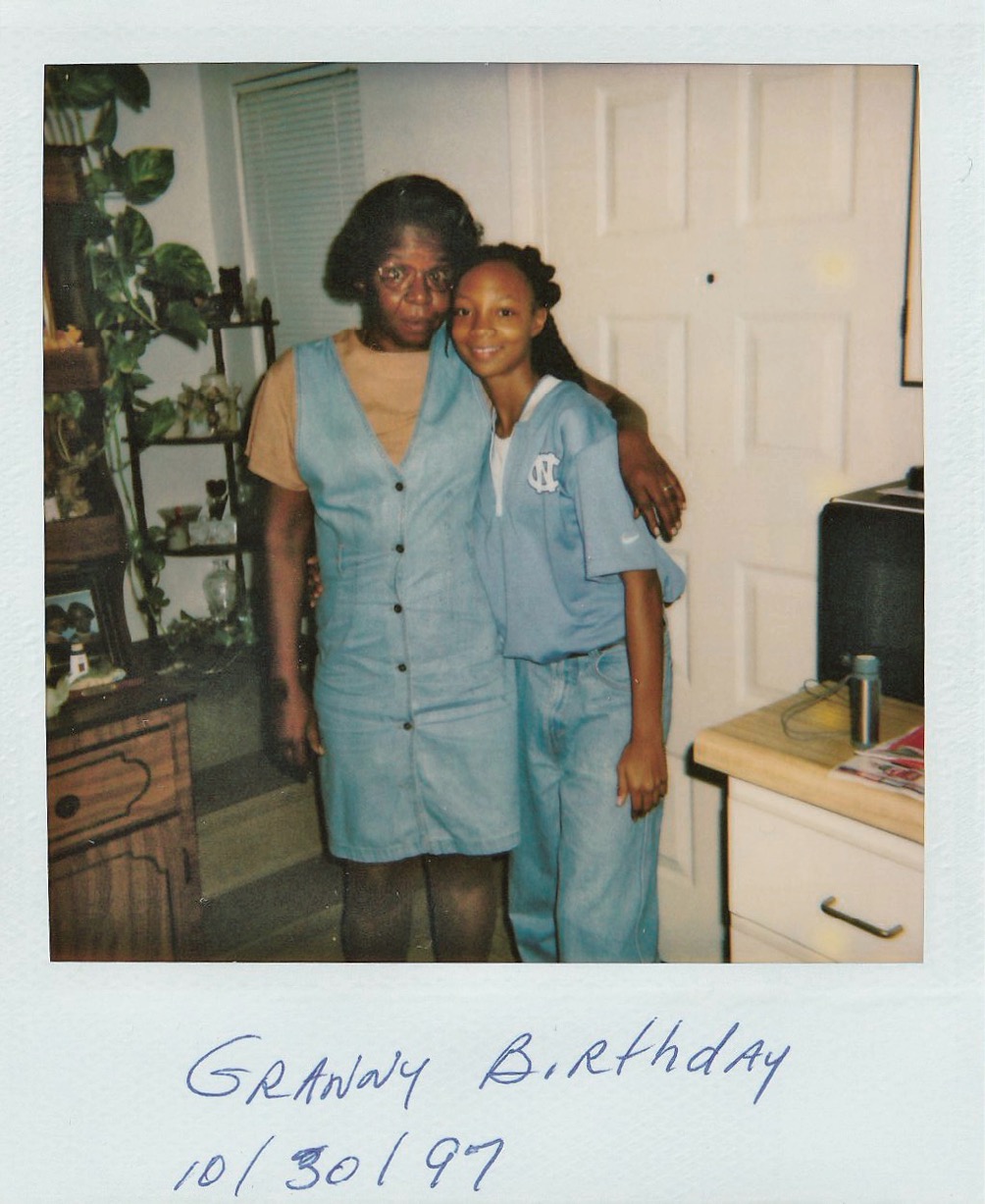

Unlike the Nikon camera that my dad used to capture family snapshots, my maternal grandmothers camera of choice was the Polaroid. Instant cameras such as Polaroids offered the built-in ease of developing the film in the moment, which saved time and money. Since she was living on a fixed income, developing pictures on the spot was the most accessible option for her. She noted the names, dates, and if space permitted, the occasion on most of her Polaroids. Her curatorial practice was straightforward, grouping her photographs in chronological order soon after the images were captured. Instead of focusing on the free-flowing moments within everyday life, my grandmother focused on capturing the more celebratory ones, like birthdays and holidays. She was a very organized woman so if I had to guess, she was creating a chronological story by intentionally preserving the images by date within their plastic sleeves, one after another.

My grandmother transitioned to the next life just a couple of months after I graduated high school in 2000. I was left with so many questions about who she was, the life she experienced as a Black woman in the South, things that brought her joy. When I trace her handwriting on a Polaroid, sometimes I get a feelingan indication of what she must have felt at that very moment. I often wonder if she realized that the record she was creating would serve as a pathway to the past from the present. As I flip through her albums, the story abruptly endsalmost mid-sentence or mid-celebration, and unexpectedly, without any warning or indication that the last set of images in the album is the final set that would ever bear her handwriting.

After she passed, instead of using Polaroids and film cameras, my family migrated to digital devices, opting to receive our images back on compact discs, made viewable on our computers. We didnt always preserve these images properlystories have been misplaced, photos went unlabeled. The digital age shifted the way we stored our images, moving away from albums and tangibility to digital and uncertainty. Technology has advanced so much, and most of us now have a camera at our side at all times through our phones. And yet, when my grandmothers voice escapes me, I feel pulled to her handwriting on her Polaroids. Like unexpectedly discovering a note left inside a picture frame, stashed in a drawer, or tucked between the pages of sacred text, this is an offering of its own. Through time and space, this is an intentional act of loveand a calling for the beneficiary of such gifts to not only consider the story of a photograph or document, but to also join their loved ones in continuing to preserve the narrative. This is how we keep stories. This is how we pass them downfrom the transitioned to the livingthroughout our lineage.

The author and her family on her fifteenth birthday

JACKSONVILLE, FL

1997

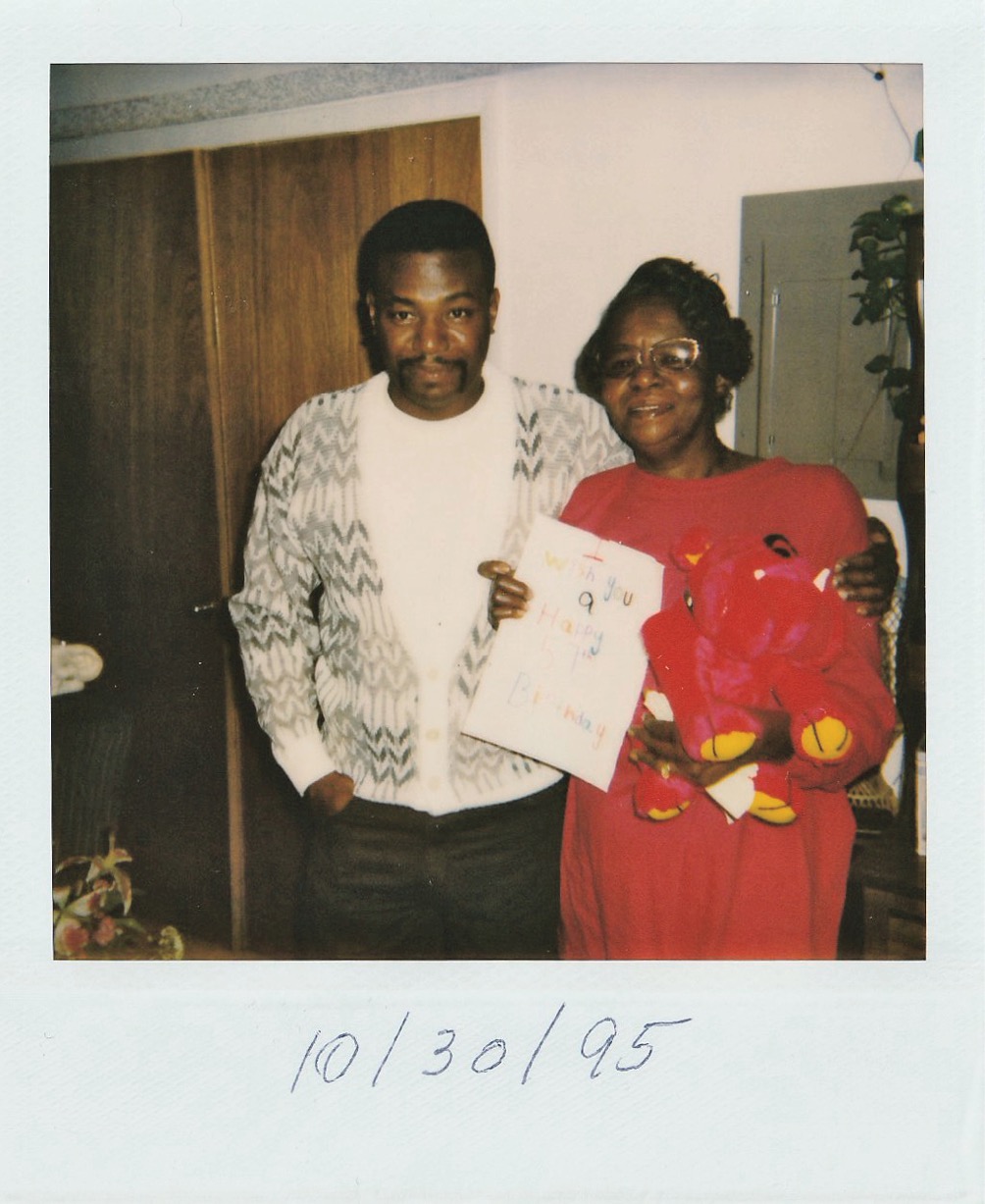

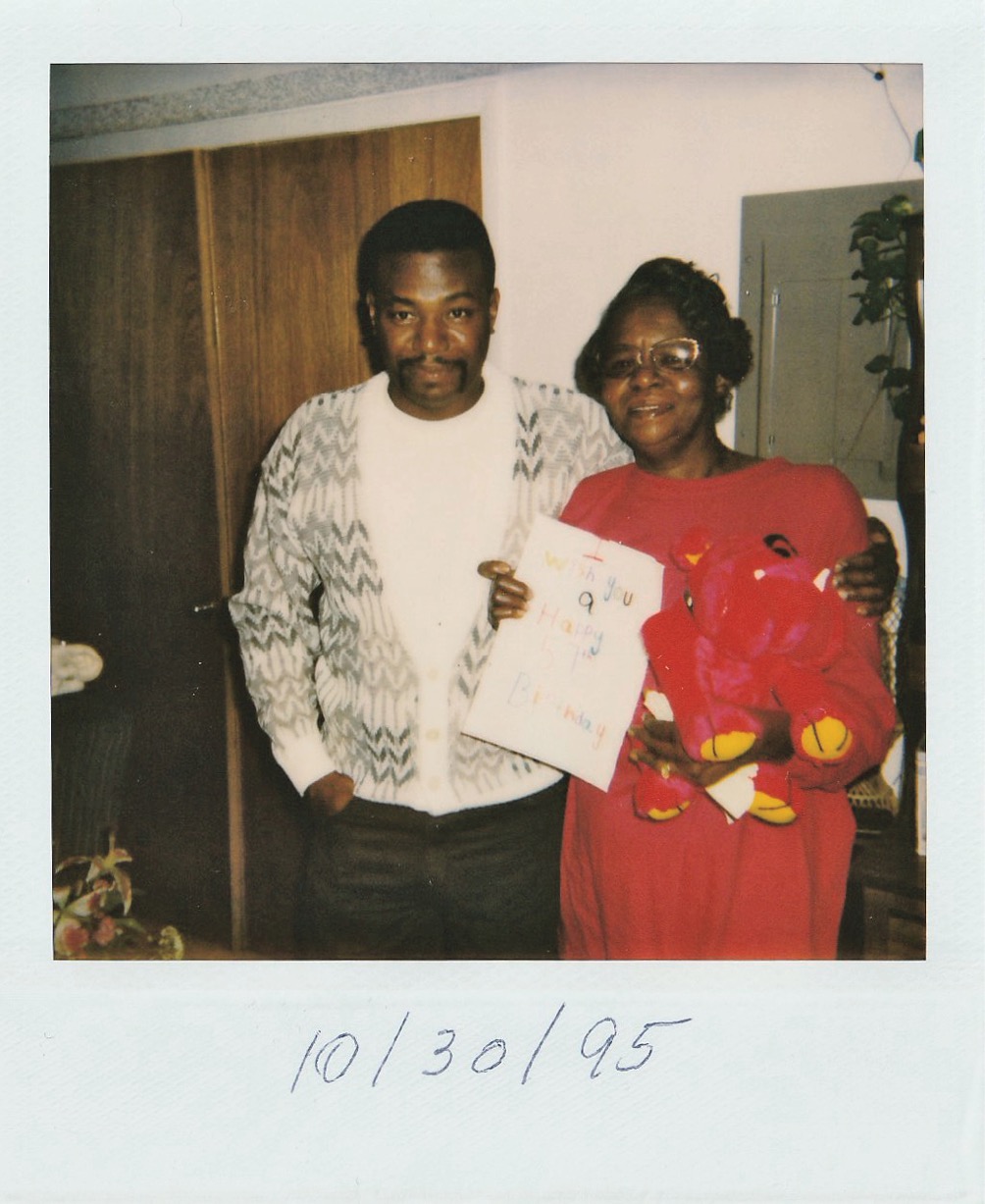

The authors dad and grandmother on her grandmothers fifty-seventh birthday

1995

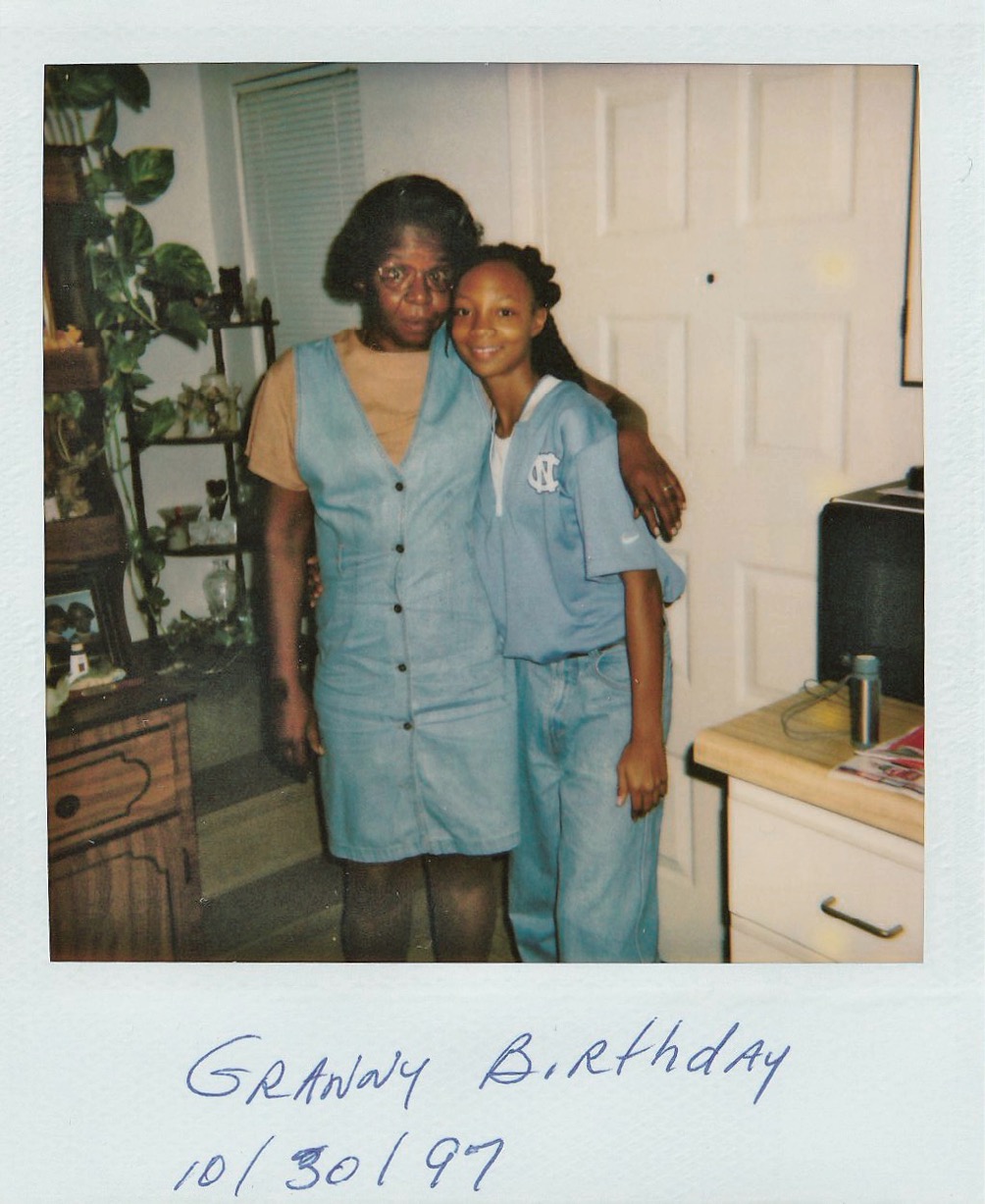

The author and her grandmother on her grandmothers fifty-ninth birthday

JACKSONVILLE, FL

1997