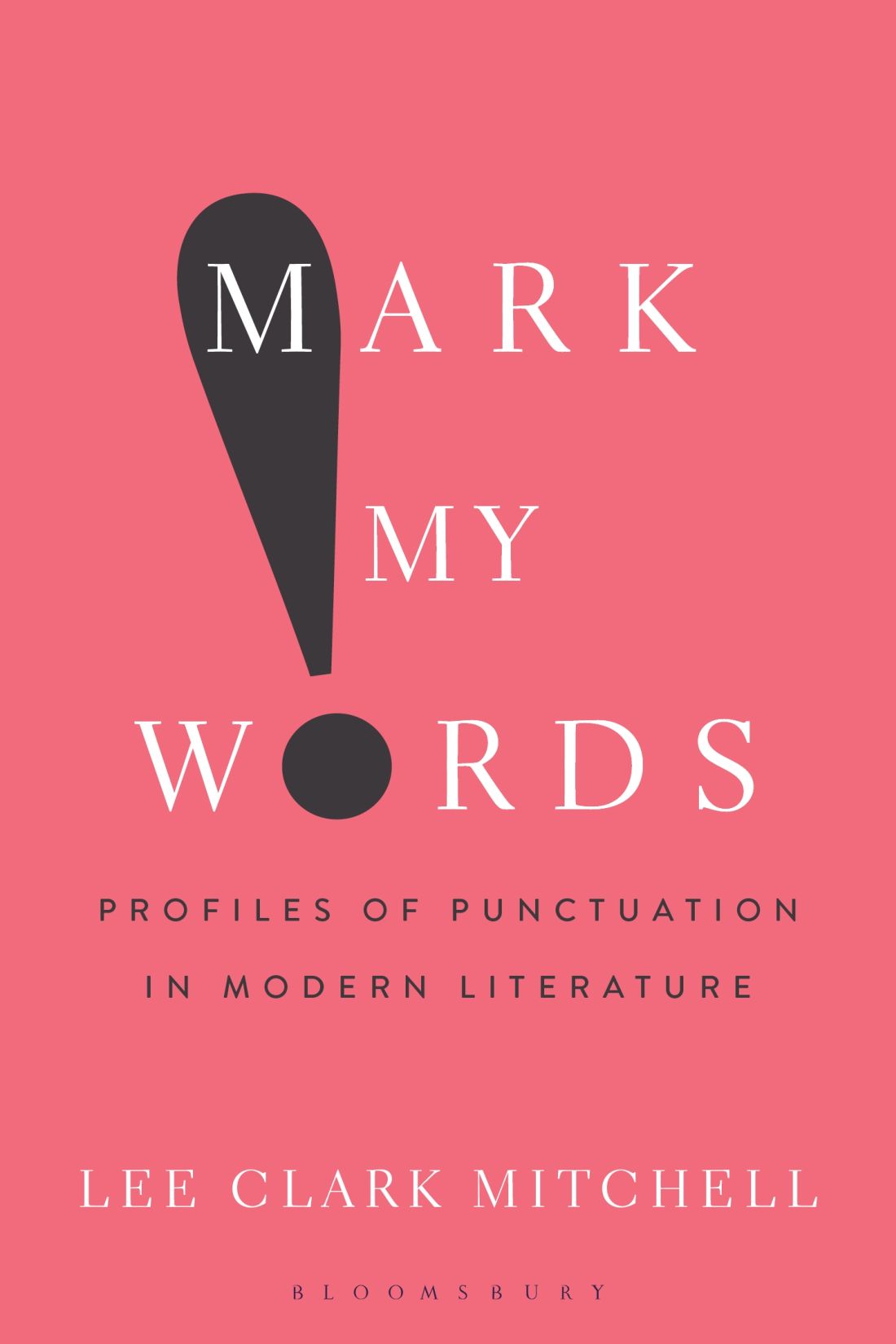

Mark My Words

For Cameron, again

A woman: without her...

Mark My Words

Profiles of Punctuation in Modern Literature

Lee Clark Mitchell

Contents

This book started as a slightly whimsical paper for a Santa Fe conference on Sights and Sites: Vision and Place in American Literature, where I opened with a hypothetical:

What if one stepped back from the echoing homonyms of this conferencephysical sites and ocular sights (or rather, geographical places and symbolic visions)to consider a map more familiar to most of us: the authorial landscape itself? And rather than gaze outward at cliffs, creeks, and crossroads, why not turn an eye instead to the topographies of punctuation that signal a writers signature style?

The paper went well enough, but once I had returned home the questions it raised continued to grip me and wouldnt let go. And I in turn badgered various friends, only to be met by an outpouring of sprightly ripostes and recommendations, surprising me with the enthusiasm shared for a subject that generally flies under the radar. After all, who would suppose that punctuation could be a conversation stopper?

As it happened, many others have been fascinated by the squiggly marks shaping the words we read. And in the course of writing this monograph, I have benefited greatly from their acumen. Dan Fischer alerted me to W. G. Sebalds silencing dashes as well as Jos Saramagos uncorseted syntax; Maria DiBattista recommended Gertrude Stein (as Mona Zhang had, memorably, years before); Brian Gingrich reminded me of Laurence Sterne and Gustave Flaubert; Jim Longenbach rightly turned me back to poetry; and Garrett Stewart plumped for Cormac McCarthy, Max Beerbohm, Toni Morrison, and even more James. Each of these four also graciously, generously, put aside their own work to read an earlier version of the manuscript, offering unwanted advice (always useful), irritating corrections (ever accepted), and wonderfully suggestive ideas for shaping the whole (on which Ive readily drawn). At Bloomsbury, Haaris Naqvi proved again a supportive editor whose enthusiasm and better sense for what a book should be forced me back to revisions. Most of all Cameron Platt was there at the beginning with challenging readings, better phrasings, even suasive punctuation. This book, as the dedication declares, was written first and above all for her, in playful celebration of an intellectual partnership that inspires, and a love that astonishes. The only way to describe the feeling is as a sequence of ever-sustaining semicolons and tumbling exclamation points... though youll have to read on to see what I mean.

What a hazard an Accent is! When I think of the Hearts it has scuttled or sunk, I almost fear to lift my Hand to so much as a punctuation.

Penciled draft (summer 1885) found among Emily Dickinsons papers (Dickinson, Letters 3: 887)

The writer is in a permanent predicament when it comes to punctuation marks; if one were fully aware while writing, one would sense the impossibility of ever using a mark of punctuation correctly and would give up writing.

Theodor Adorno (1956) (Adorno 305)

The pace at which this world unfolds is supervised by punctuation.

Fredric Jameson (1961) (Jameson, Sartre 41)

The ear does it. The ear is the only true writer and the only true reader. I have known people who could read without hearing the sentence sounds and they were the fastest readers. Eye readers we call them. They can get the meaning by glances. But they are bad readers because they miss the best part of what a good writer puts into his work.

Remember that the sentence sound often says more than the words. It may even as in irony convey a meaning opposite to the words.

Robert Frost, letter to John Bartlett, February 22, 1914 (Frost 176)

A woman without her man is nothing.

A woman: without her, man is nothing.

Adorno, Theodor W. Punctuation Marks (1956). Notes to Literature, vol. 1, edited by Rolf Tiedemann; translated by Shierry Weber Nicholsen. New York: Columbia University Press, 1991. 91-97. Permission granted by Shierry Weber Nicholsen.

Cummings, E. E. [Edward Estlin]. Complete Poems: 1904-1962, edited by George J. Firmage. since feeling is first. Copyright 1926, 1954, (c) 1991 by the Trustees for the E. E. Cummings Trust. Copyright (c) 1985 by George James Firmage, Tumbling-hair/ picker of buttercups/ violets. Copyright 1925, 1953, (c) 1991 by the Trustees for the E. E. Cummings Trust. Copyright (c) 1976 by George James Firmage, r-p-o-p-h-e-s-s-a-g-r. Copyright 1935, (c) 1963, 1991 by the Trustees for the E. E. Cummings Trust. Copyright (c) 1978 by George James Firmage. Used by permission of Liveright Publishing Corporation.

Dickinson, Emily. THE LETTERS OF EMILY DICKINSON, edited by Thomas H. Johnson, Associate Editor, Theodora Ward, Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Copyright 1958 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Copyright renewed 1986 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Copyright 1914, 1924, 1932, 1942 by Martha Dickinson Bianchi. Copyright 1952 by Alfred Leete Hampson. Copyright 1960 by Mary L. Hampson.

Dickinson, Emily. THE POEMS OF EMILY DICKINSON, edited by Thomas H. Johnson, Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Copyright 1951, 1955 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Copyright renewed 1979, 1983 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Copyright 1914, 1918, 1919, 1924, 1929, 1930, 1932, 1935, 1937, 1942, by Martha Dickinson Bianchi. Copyright 1952, 1957, 1958, 1963, 1965, by Mary L. Hampson.

Frost, Robert. The Letters of Robert Frost. Volume 1, 1886-1921, edited by Donald Sheehy, Mark Richardson, Robert Faggen. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014. Permission granted by Robert Frost Estate and Copyright Trusts.

Giovanni, Nikki. Cotton Candy on a Rainy Day and an excerpt from Habits from The Collected Poetry of Nikki Giovanni by Nikki Giovanni. Copyright compilation 2003 by Nikki Giovanni. Used by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Jameson, Fredric. Sartre: The Origins of a Style. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1961. Permission granted by Yale University Press.

Williams, William Carlos. William Carlos Williams: Selected Poems, edited by Charles Tomlinson. New York: New Directions, 1985.

Maneuvering through unsettled landscapes of literary expression demands the occasional guard rails and blinking lights of punctuation: the jersey dividers and cautioning signs that serve as typographical tools for modifying syntax. Creativity needs constraintsand flourishes within themrequiring that unruly strings of words be policed into governable shape, transforming potential conflicts into the plausible constructions we intend (hence the crucial comma in lets eat, grandma).).

Still, poet and critic remain at odds over whether punctuation clarifies meaning or merely reaffirms what syntax already enacts, with clauses in proper order, depending on marks solely for stress. In either case, it might be better to think of punctuation less as regulation (like Adornos imagined traffic stop, where speeding and prohibited turns are rigidly patrolled) than as a choice among distinct rhetorical effects, say commas rather than periods, or even more intriguingly rather than dashes. Keep in mind that ). If punctuation is not essential to sorting out verbal meaning, then, the question that remains is how it does or (more interestingly) does not imitate the effect of spoken stresses and pauses. What happens when we no longer consider it simply a marker for rhythms of speech?