Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

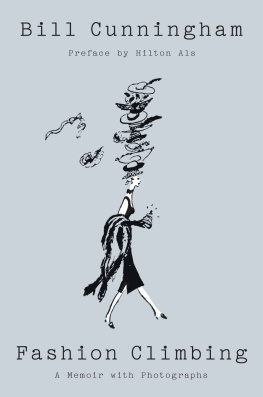

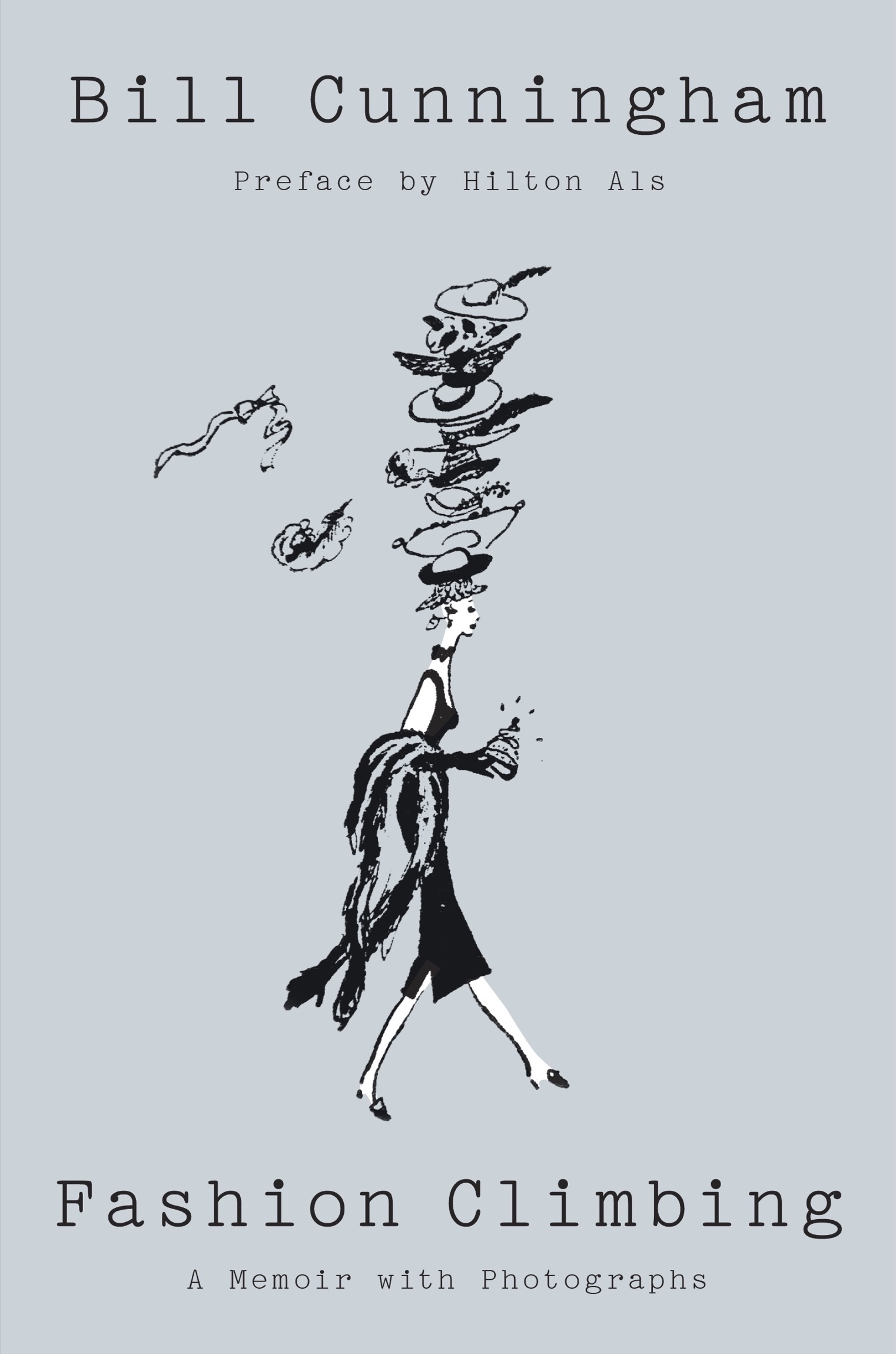

All images, unless credited below, are by Bill Cunningham. Photographs by Anthony Mack. Used with permission.

Photographs and illustrations appear courtesy of The Bill Cunningham Foundation LLC.

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the authors alone.

PREFACE

by Hilton Als

I loved him without knowing how to love him. If you think of love as an activitya purposeful, shared exchangewhat could anyone who was lucky enough to be acquainted with Bill Cunningham, the late, legendary New York Times On the Street and Evening Hours style photographer, writer, former milliner, and all-around genial fashion genius, really offer him but ones self? I dont mean the self we reserve for our deepest intimacies, the body and soul that goes into life with another person. No, the Cunningham exchange was based on something else, was profound in a different way, and I think it had to do with what he inspired in you, what you wanted to give him the minute you saw him on the street, or in a gilded hall: a certain faith and pride in ones public personathe face that I face the world with, baby as the fugitive star, the princess Kosmonopolis, has it in Tennessee Williamss Sweet Bird of Youth. Like the princess, Bill knew a great deal about surfaces; unlike the princess, though, he was never fatigued or undone by his search for that most elusive of sartorial qualities: style. You wanted to aid Bill in his quest for exceptional surfaces, to be beautifully dressed and interesting for him, because of the deep pleasure it gave him to notice something he had never seen before. Even if you were not the happy recipient of his interestthe subject of his cameras click click click and Bills glorious toothy smilethere were very few things as pleasurable as watching his heart beat fast (you could see it behind his blue French workers jacket!) as he saw another fascinating woman approach, making his day. Thats just one of the things Bill Cunningham gave the world: his delight in the possibility of you. And you wanted to pull yourself togetherto gather together the existential mess and bright spots called your Ithe minute you saw Bills skinny frame bent low near Bergdorfs on Fifth Avenue and Fifty-Seventh Street, his spot, capturing a heel, or chasing after a hemline, because here was your chance to show love to someone who lived to discover what you had made of yourself. His enthusiasm defined him from the first. It permeates this, his posthumous memoir, Fashion Climbing, which covers the years Bill worked in fashion before he picked up a camera. (He published only one book during his lifetime, 1978s Facades, which starred his old friend, portraitist Editta Sherman, dressed in a number of period costumes Bill had collected over the years. He was not happy with the book but he was a perfectionist and anti-archival in his way of thinking, so how could a book satisfy his need to move forward, always? Fashion Climbing is, in many ways, his most unusual project. Of course at the end of his memoir he uses his story to help point the way toward fashions future.)

As a preternaturally cheerful person, Bill seemed not to ever feel aloneafter all, he had himself. Born to a middle-class Irish Catholic family in Depression-era Massachusetts, Bill was raised just outside Boston; as a little boy he loved fashion more than he longed for anything as unimaginative as social acceptance. He begins Fashion Climbing this way:

My first remembrance of fashion was the day my mother caught me parading around our middle-class Catholic home.... There I was, four years old, decked out in my sisters prettiest dress. Womens clothes were always much more stimulating to my imagination. That summer day, in 1933, as my back was pinned to the dining room wall, my eyes spattering tears all over the pink organdy full-skirted dress, my mother beat the hell out of me, and threatened every bone in my uninhibited body if I wore girls clothes again.

A familiar queer story: being attacked for ones interest in being ones self. Still, there is no rancor when Bill says: My dear parents gathered all their Bostonian reserve and decided the best cure was to hide me from any artistic or fashionable life. But this was not possible. He would be himself, despite the pain. After he found work as a youth in a high-end department store in Boston, there was no stopping him, really, and no turning back. After Boston, the move to Manhattan where he lives for a time with more disappointed relatives, secures a job at Bonwits, and designs his first hats. The startling optimism of his outlook! In 1950, when he was twenty-one, he was inducted into the army. At first I was heartbroken at the thought of giving up all the years of hard work, he writes, but I never had a mind that dwelled on the bad. I always believed that good came from every situation. He would love despite the cruelty he had been given. Its like watching a movieBill post-Bonwits, working as a janitor in a town house in exchange for a room to show his hats. The other residents are straight out of Truman Capotes Breakfast at Tiffanys and still, despite the mayhemtheres even a floodBill presses on, and presses against our hearts because of his acceptance of others while maintaining very strict standards for himself. Living on a scoop or two of Ovaltine a day when things just werent happening financially, he fed on fashion and beauty; there was no shortage of it in all those glistening store windows advertising so much thats been forgotten. I dont think its too much to compare Bill to the Catholic art collectors John and Dominique de Menil, who regarded their commitment to beauty and supporting artists as a spiritual practice, a form of attention that was a kind of loving discipline: you could love God through his creators and their creations. Theres a nearly unbearable moment in the 2010 documentary Bill Cunningham New York when Bill is asked about his faithhis Catholicism. Its the only time he turns away from the camera; his body folds in on itself. I turned away from the screen in that moment, just as, when Bill was the smiling recipient of the Council of Fashion Designers of Americas Media Award in Honor of Eugenia Sheppard in 1993he collected the award on his bicycle perch, of courseI turned away, too: How could such goodness be possible? In the world of