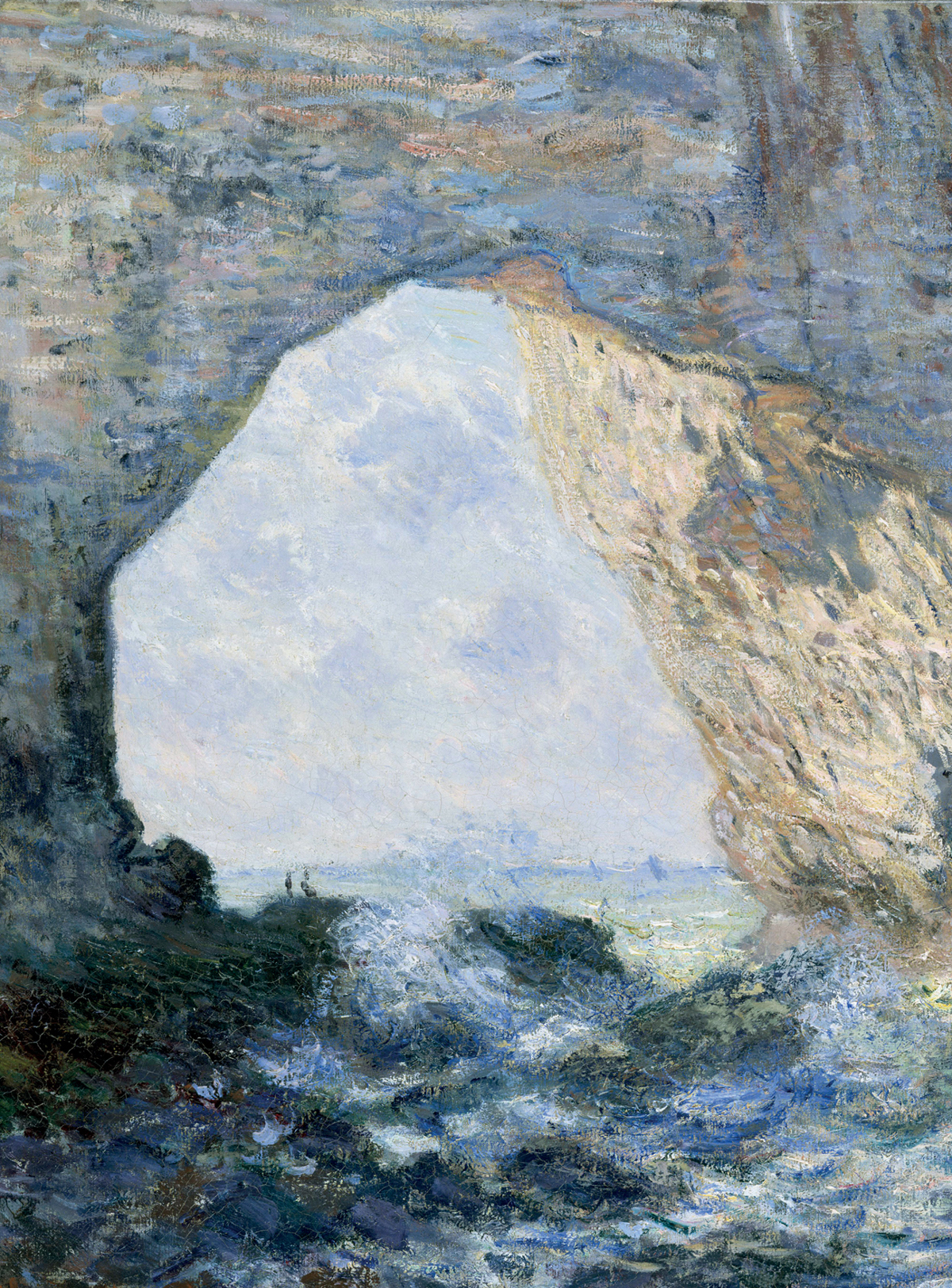

The Manneporte, 1883.

About the Authors

James H. Rubin is professor in the department of art at Stony Brook University, New York, where he teaches art history, theory and criticism, specializing in nineteenth-century France. He taught previously at Harvard, Boston University, Princeton and the Cooper Union. His books include studies of Manet, Delacroix, Courbet and Impressionism; most recently he is the author of How to Read Impressionism: Ways of Looking.

Your hand in mine, lets help others always to see better.

Claude Monet, quoted by Georges Clemenceau

First published in the United Kingdom in 2020 as Monet

ISBN 978-0-500-20447-4

by Thames & Hudson Ltd, 181A High Holborn, London WC1V 7QX

and in the United States of America by Thames and Hudson Inc., 500 Fifth

Avenue, New York, New York 10110

Monet 2020 Thames & Hudson Ltd, London

Text 2020 James Rubin

This electronic version first published in 2020 in the United Kingdom by

Thames & Hudson Ltd, 181A High Holborn, London WC1V 7QX

This electronic version first published in 2020 in the United States of America by

Thames & Hudson Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10110

To find out about all our publications, please visit

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced

or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

eISBN 978-0-500-77506-6

eISBN for USA only 978-0-500-77513-4

Contents

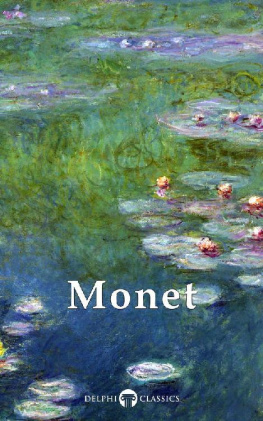

The future of modern art was decided on the shores of Normandy. It was a fateful day when Oscar Claude Monet took his caricatures to show at a local frame shop in his home town of Le Havre. In the window he noticed some modest oils by another artist, Eugne Boudin, who spent most of his time painting out on the nearby beaches. Although Monet earned something of a reputation for his witty drawings, and at first he disliked Boudins style, he eventually followed in his elders footsteps to begin painting out of doors. He later claimed he owed Boudin everything for helping to open his eyes. He also dropped his given first name.

From this simple beginning came one of the worlds most famous painters, admired on all continents and in most cultures. Monets name was and still is the first associated with the art movement called Impressionism, and Impressionism is usually said to have caused a revolution that led to modern art. The paragraph above exemplifies three of the reasons why. First, caricature is a kind of shorthand, usually an innate gift, that allows an artist to summarize and accentuate aspects of his subject that help one see it more clearly. Its usual purpose is to poke fun, but for Monet and his cohorts, the ability to render the essential through apparently simple, intuitive means was an important factor underlying Impressionisms wide appeal. Second, Normandy was by Monets time a place of tourism and prosperous bourgeois leisure. Parisians and foreigners alike took trains or ferries to enjoy glorious summer sunlight cooled by fresh breezes from off the water. Its beaches were wide and shallow, with firmly packed sand that encouraged languid strolling and offered a firm enough support for parasols and lightweight chairs. These modern conditions, economic and technological, were the basis for the kind of mobility and recreational pleasures Impressionism exemplified in Normandy and which we still enjoy today. Finally, painting out of doors, at the seashore, in the mountains, in cities or in the countryside, is called painting en plein air. That is, rather than making sketches and studies as the basis for more finished work produced in the studio, the Impressionist worked on pictures meant as the end product while immersed in his or her surroundings. Even if they were finished or touched up in the studio, Monets pictures virtually always reflected immediate, on the spot observation, or at least he made it seem so. Their ostensible authenticity guaranteed a continuous experience of the scene he was depicting. His paintings could therefore claim to be both natural and true.

These factors are symptomatic of a larger issue for Monets painting and Impressionism in particular, but also for art as a whole. Painting directly from observation of the motif could imply the objectivity of the Impressionist vision. In this respect, it corresponded to the empirical ethos of scientific method, embodied by the nineteenth-century philosophy of Positivism and rivalled only, though without colour, by the recent invention of photography. Yet aside from colour, the sketch-like execution of Impressionist paintings distinguished its physical appearance from photography, implying through its rapidity the intuitive spontaneity of Impressionist observation. This personalization of technique, however, undermined or at least sets up a dialogue with Impressionisms claim to objectivity. That is, unless corrected by effort and training and repressed by careful finishing, each artist has a specific style of painting much like handwriting. While it authenticates the artists vision, it does so only by displaying its singularity. So the immediacy of Impressionist painting betrays its subjective element, the artists individuality. Called temperament in the art language of the nineteenth century, this personal element was extolled as essential by advanced critics of the time, for example by the great poet Charles Baudelaire. In the 1860s, the novelist-to-be mile Zola defined art as a corner of nature seen through a temperament. Behind each picture, Zola looked for a man, by which he meant an individual artistic personality. Observation is the beginning, but temperament leaves its mark. Each of us, the latter pointed out, sees reality through our own personal screen.

Every artwork of course combines both objective and subjective elements. The same is true even in photography, and yet there have been times when artists tried to hide one feature or the other, for example when an apprentice works in a studio run by a master, or when producing art on commission for a rulers propaganda. Opposite examples might be when an artist is trying for expressive effects, as in German Expressionism or Surrealism, movements that were in part reactions against the naturalism later generations came to associate with Impressionism. Within the Impressionist circle itself, there were differences and disputes. But if one painter comes to mind first when referring to the movement, it is Claude Monet. And if one painter embodies the malleability of the term and its interpretations, it is again Monet. For he lived far longer than his colleagues, and his work never stopped developing. Impressionism came to mean whatever Monet happened to be doing at the time.

For example, when social conflicts and political upheavals eventually led many at the end of the nineteenth century to lose faith in both science and public discourse, the subjective element emerged as primary in art, as many artists, writers and philosophers looked within themselves for truth and meaning. Monets late work embodied a parallel critique of objectivity discovered through his own experience. Still, however, we know that no man is an island. Even in the splendid isolation of the magnificent gardens he designed for himself in the Normandy village of Giverny, Monets self-reflection, evidenced by the mirroring surfaces of his lily pond, were responses to his time. Nowhere was this aspect better demonstrated than by the commission of the

Next page