Published by

OMEGA PUBLICATIONS INC.

New Lebanon NY

www.omegapub.com

1993, 2011 by Omega Publications

First edition 1993

Second revised edition 2011

1993 Coleman Barks translations

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher.

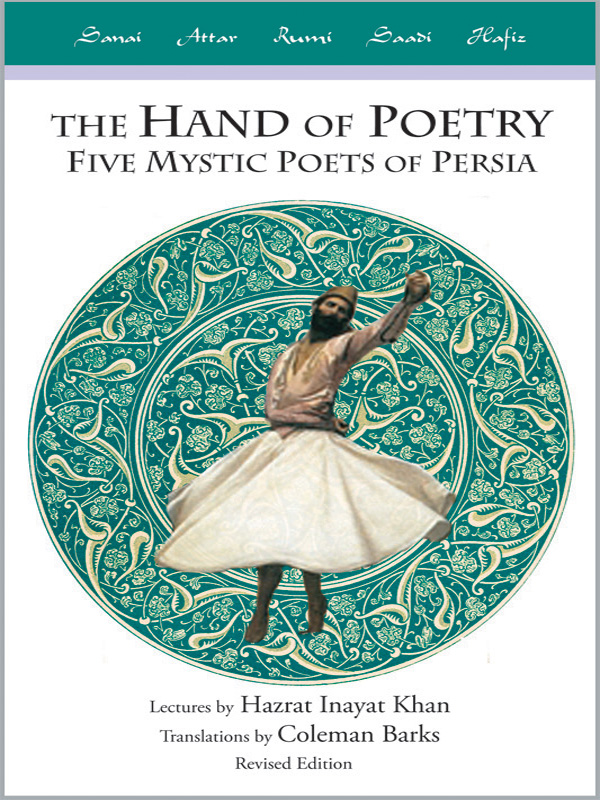

Cover art detail of The Whirling Dervishes by Jean-Leon Gerome

and Islamic motif courtesy of Dover Publications

Cover design by Sandra Lillydahl

This edition is printed on acid-free paper

that meets ANSI standard X39-48.

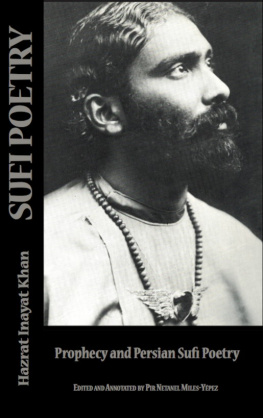

Inayat Khan 1882-1927

Barks, Coleman, 1937

Hand of poetry; five mystic poets of Persia.

Includes introduction, publishers preface,

translators preface, biographical notes

1. Sufi poetry, PersianTranslations into English.

2. Persian poetryTranslations into English

I. Inayat Khan 1882-1927 II. Barks, Coleman, 1937 III. Title

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011934244

Printed and bound by McNaughton-Gunn

in the United States of America

Table of Contents

Additional titles by Hazrat Inayat Khan

The Art of Being and Becoming

Awakening of the Human Spirit

The Complete Sayings of Hazrat Inayat Khan

Creating the Person; A Practical Guide to the Development of Self

The Gayan; Notes from the Unstruck Music

Mastery Through Accomplishment

The Music of Life; The Inner Nature and Effects of Sound

Nature Meditations

The Souls Journey

Song of the Prophets; The Unity of Religious Ideals

Spiritual Dimensions of Psychology

The Complete Works of Hazrat Inayat Khan series

Other titles on classical Sufism

The Man of Light in Iranian Sufism

Henry Corbin

The Story of Layla and Majnun

by Nizami

Foreword

This book, The Hand of Poetry, offers entrance into a world of beauty and truth. Its method is two-fold. First it presents five important lectures on Persian poetry given by Pir-o-Murshid Inayat Khan, who brought Sufism to the West. Then it offers fresh translations by the poet Coleman Barks of some of the poetry Inayat Khan discusses, designed to provide readers with ready access to at least a sample of this wondrous literature, still not easy to find in English. Thus, The Hand of Poetry represents a brief, but reasonably comprehensive, introduction to one of the great literatures of the world, until recently ignored in the West.

Persian literature of the 13th century, described by a leading authority, Professor Annemarie Schimmel, as the zenith of the vast Islamic literature (she asserts it would require a large team of scholars to master even one branch of it), is certainly still a hidden treasure, despite the efforts of many scholars during the last century. Very few people in the West have learned the language, Farsi, and the translations have often left much to be desired in terms of their poetic appeal. This situation is now being vigorously corrected by Coleman Barks, our present translator, whose wonderfully lively and poetically powerful translations of Jelaluddin Rumi fill more than half a dozen much admired volumes, and by other contemporary poets as well. Nevertheless, the vast majority of classical Persian poems exist only in manuscript, never having been printed even in the original language! Even the lives of most of these poets do not appear in standard encyclopedias, so the translator has helpfully added brief accounts of what little is known about them.

Inayat Khan was reared in a highly artistic, mainly musical household in Baroda, Gujerat, India in the 1880s and 90s. One of the household languages was Urdu, an Indian adaptation of Farsi, and he took a special interest in poetry already in early youth. The poetry he discusses here was known to him for virtually his whole life, and it came as something of a shock when he came to the West in 1910 to discover that very few people had even heard of these great poets. When he spoke about them, he spoke (as always) entirely ex tempore, never using any notes as far as we know. His work in presenting these poets was, as in many other areas, pioneering work. Omar Khayyam was the only one of these poets well-known to Western audiences, largely because of Edward Fitzgeralds translation of the Rubaiyat, considered today of dubious value as a translation.

Now, seventy years later, this poetry has become much better known in the West, yet it is still possible to ask a literature professor if she has heard of Jelaluddin Rumi and receive a negative answer. Therefore, it is highly apropos to continue Inayat Khans pioneering effort by this new presentation of his teachings and the work of the poets themselves.

This book also represents a significant step forward in the presentation of the texts of Inayat Khan. This is the first time his lectures have been presented in a book for the public in words as close as possible to the actual words he spoke. This has been made possible by the scholarly series, The Complete Works of Hazrat Pir-o-Murshid Inayat Khan (East-West, The Hague, 1988). The second volume of that series (1923 I, published in 1989), includes these five lectures. The Complete Works provides a text of each lecture based on the earliest and best manuscript, most often a shorthand record. In the case of these lectures, however, no shorthand record has survived (Inayat Khans secretaries were not travelling with him), and our basic manuscript is typewritten. We do not know who took down the lecture or prepared the typescript, which is slightly edited; it may well have been Rabia Martin, the leader of the Sufi Center in San Francisco. Because The Complete Works is restricted in circulation, the present publication makes widely available for the first time Inayat Khans actual words.

The lecture series represented here took place on Tuesday afternoons at 2:30 p.m. from April 3rd to May 8th, 1923, in the gallery of the Paul Elder Bookstore, the leading such institution in the San Francisco of that day. Inayat Khan was billed as A Pilgrim of Music, Literature and Philosophy, and he gave two other series, one on music and the other on spiritual philosophy, on Wednesday mornings and Thursday evenings respectively. Miss Hayat Stadlinger, still a resident of Oakland, California, vividly recalls attending these lectures as a young woman. She recalls that Inayat Khan sat in the vestibule and warmly greeted each person coming in, with a display of white calla lilies at his feet. She also recalls that the audience was quite large and enthusiastic. A payment of one dollar was required (not inexpensive in those days), and the Gallery, located at 239 Post Street, was proudly declared to be air conditioned and vitalized by electro-ozone equipment (perhaps this will give pause to those who imagine that the New Age movement began in the sixties). Unfortunately, the text of one lecture, the second in the series, on Omar Khayyam, appears not to have been preserved. The beautifully prepared brochure gives an unmistakable flavor of the times, and so we reproduce below the page referring to the present series.

I would like to end on a personal note. I am one of the editors (along with Munira van Voorst van Beest, now deceased) of