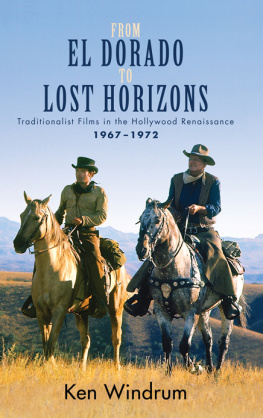

From El Dorado to

Lost Horizons

From El Dorado to

Lost Horizons

Traditionalist Films in the

Hollywood Renaissance, 19671972

Ken Windrum

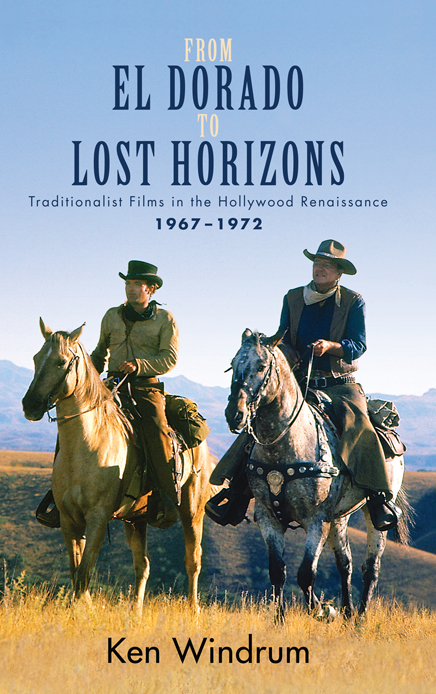

Cover image: El Dorado (Howard Hawks). Paramount Home Video/Photofest

Paramount Home, 1966.

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2019 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Windrum, Ken, 1962 author.

Title: From El Dorado to Lost Horizons : traditionalist films in the Hollywood renaissance, 19671972 / Ken Windrum.

Description: Albany : State University of New York Press, [2019] | Series: SUNY series, horizons of cinema | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018021846 | ISBN 9781438473970 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781438473987 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Motion picturesUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Motion picturesSocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC PN1993.5.U6 W56 2019 | DDC 791.430973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018021846

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Illustrations

Acknowledgments

I want to thank those who have helped out over this projects very long gestation.

The late Bob Sklar first suggested a version of this idea in the 1990s by highlighting the significance of the late 1960s and early 1970s in American film history and encouraging my work on the period.

My dissertation committee at UCLANick Browne (chair), Steve Mamber, Peter Wollen, and Jan Reiffgave me advice and support over my years in the PhD program.

Fellow students and now professional colleagues, Vincent Brook and Jerry Mosher encouraged me to move this from dissertation to published work. Both gave constructive feedback when I was proposing this as a manuscript to SUNY Press.

At the press, my editor Murray Pomerance has been patient and helpful; hes given many good suggestions and much advice over various iterations of this work. Also at the press, James Peltz has been encouraging and given much thoughtful advice. Rafael Chaiken has fielded many of my inquiries there. I also wish to thank the two anonymous readers, who did much to improve this work.

Once in production, Ryan Morris helped guided me through copyediting. Aimee Harrison made a key suggestion about the table of contents and Daniel Otis did some very thorough overall copyedits that improved the books quality.

My colleagues at Pierce CollegeJeff, Jill, Tracie, Matt, Rob, and Seanhave been wonderful to work with and have shown interest in this seemingly endless project. Yes, the book is finally arriving.

Various people in my personal life have been extraordinarily helpful. My late father George and my mother Gloria constantly encouraged and supported me, as did my sister Gayle and her family. Several othersKathleen, Frank, Elizabeth, Jay, Susan, Beth, Christeen, Susanne, Cindy, and Brandonhave provided emotional support, practical advice, good ideas, and encouragement. In particular, Kathleen read over my introduction in the very final stages and helped out immensely.

I thank everyone.

Foreword

A canon of groundbreaking motion pictures made between the mid-1960s and late 1970s continues to fascinate cinephiles. Film historians favor these productions so much that the entire period is typically called the Hollywood Renaissance. They have created an ironically stable characterization of an unstable, tumultuous era that focuses on innovative filmmakers challenging classical Hollywoods norms with iconoclastic, maverick movies per Drew Caspers phrase (Casper xvxvii). Meanwhile, a larger group of more conventional-seeming films is either ignored or marginalized by historians as bad, clueless objects against which more favored productions can shine, even though many were financially successful and well-reviewed. Discussing these traditionalist movies provides an alternative account of the period.

The era is usually described by historians as a result of the major studios economic woes after both the sale of their theater chains and the overall box-office decline caused by television. Simultaneously, young filmmakers influenced by European art cinema began to produce innovative works with more overt sociopolitical content, greater frankness in representing violence, sex, and use of profanity, and an antiestablishment, often left-wing perspective. The financial success of The Graduate (Mike Nichols, 1967), Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967), and 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968), and especially the surprise profits of the low-budget Easy Rider, are credited with spawning a wave of similar titles over the next several years. Drew Casper discusses how these have become a critical canon of maverick films with radical formal experimentation and uncompromised liberalist critique (xvixvii).

A few choice quotes typify the dominant historical construction of the period as groundbreaking and revolutionary. For instance, Peter Biskinds popular Easy Riders, Raging Bulls describes how in 1967 Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate sent tremors through the culture and ushered in a true golden age of films that defied traditional narrative conventions, that challenged the tyranny of technical correctness, that broke the taboos of language and behavior, that dared to end unhappily (Biskind 1516). From a more academic perspective, Robert Sklars Movie-Made America (1994 edition) created a framework for understanding the period. He discusses how M*A*S*H (Robert Altman, 1970), 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Little Big Man (Arthur Penn, 1971), while overturning movie conventions both aesthetically and ideologically, found such wide popular approbation as their baby-boomer audience was primed for artistic rebellion as few audiences before or since (Sklar 325). Finally, a more focused work, Glenn Mans Radical Visions: American Film Renaissance 19671976, exhaustively typifies this dominant approach as he gives fifteen paradigmatically maverick auteur texts close, insightful readings. Like many accounts, including Biskinds, he privileges Bonnie and Clyde, which opened the way for a new American cinema when its new wave characteristics and its shocking, honest treatment of sexual and violent themes paved the way for other filmmakers to punctuate the American scene with bold, unsettling achievements (Man 31). There only a few exceptions to this focus on the maverick, such as Drew Caspers