Spaghetti Westerns

the Good, the Bad and the Violent

Spaghetti Westerns

the Good, the Bad

and the Violent

A Comprehensive, Illustrated

Filmography of 558 Eurowesterns

and Their Personnel, 1961-1977

by

Thomas Weisser

Foreword by CRAIG LEDBETTER

Foreword by TOM BETTS

Comments by WILLIAM CONNOLLY

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina, and London

l

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-1169-3

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

1992 Thomas Weisser. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, 1966 (Photofest)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

This book is dedicated to my children,

Jeff and Jessica

* * *

I wish to thank

Craig Ledbetter and Tom Betts

for their help, without which

this book could not have been written.

* * *

I also wish to thank the following people

for their help and contribution to the cause:

Bill Connolly, Dave Todarello, Tim Paxton, Bill George,

Louis Paul, Eric Hoffman, Alain Petit, Ally Lammaj,

Jorge Patio and Rick Martinez.

Contents

Foreword

(Craig Ledbetter)

The term Spaghetti Western brings an instant sneer to any "serious" critic. In the United States, except for a few token acknowledgments to the films of Sergio Leone, no one has written an overview of this most curious film phenomenon. Over 600 European Westerns were made from the early 1960s to the late 1970s, yet very few pages of text have explored the plots of these films or detailed the contributions made by the many excellent professionals in front of and behind the cameras. Now, thanks to exhaustive research and hours of viewing by Thomas Weisser, you're holding just such a book at last.

As early as 1961, the Italians were producing imitations of standard U.S.styled Westerns. These films featured such stars as Richard Basehart, Rod Cameron, Gordon Scott, and Edmund Purdom, among others, and until 1964 these movies were basically "B" Westerns filmed on foreign soil.

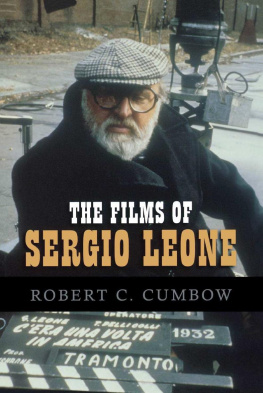

Then in mid-decade, Sergio Leone (along with star Clint Eastwood, composer Ennio Morricone, and cinematographer Massimo Dallamano) created what quickly became known as the Spaghetti Western. With three films, A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More, and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, the staples of this genre were created and put into motion, including: the no-name bounty hunter who cared for nothing except money, the search for a fortune in gold, and the settling of accounts for a betrayal in attaining said fortune. All of these soon-to-become clichs had their origins in the Leone trilogy. There were a group of directors who took Leone's work and expanded it into many other areas. The other Sergios, Corbucci and Sollima, used the Spaghetti Western to address political concerns often found in the many Third World countries that, ironically, formed the traditional audience for these films.

As you read this volume, you will also discover that certain Spaghetti Western characters were so popular that an entire series of films based on their exploits was produced. Django, Sartana, Ringo, and Sabata are just a few of the more prolific ones. The "Django" series is a perfect example of how fractured and perverse the Spaghetti Western universe could become. Sergio Corbucci's Django featured Franco Nero as the laconic, grizzled, world-weary gunfighter whose main motivation was revenge. Alberto De Martino's Django Shoots First would feature Glenn Saxon as a more traditional Western hero tracking down his father's killer. True perversity reigns in Giulio Questi's Django Kill, a hallucinogenic gorefest starring Toms Milian. Here, Django is a wronged Mexican peon who must fend for himself against homosexual cowboys, talking parrots and an entire town of greed-infected citizens.

The American actors who headed overseas to become Euro-sensations include a list of has-beens and never-weres. After you see them in several Spaghetti Westerns, however, you realize that actors like Craig Hill, Brad Harris, and Robert Woods deserve their place in the spotlight as much as their better known counterparts like Stewart Granger, Charles Bronson, and Jack Palance who, no doubt, felt as though they were slumming, at best.

After several years of successfully ripping off all the characteristics of the Leone universe, the Spaghetti Western began to look for other modes of expression. The comedic Trinity series (featuring Terence Hill and Bud Spencer) became so popular that this slapstick parody of Spaghetti Western conventions became a genre unto itself. Providence, Carambola, and Invincible were just some of the characters used to ape the more well-known Trinity boys. By this time in the seventies, final nails were being hammered into the coffin of the Spaghetti Western. The emerging Kung Fu genre was even stirred into the pot (without a doubt, one of the more bizarre cross-fertilizations of genres ever) if for no other reason than to try and lengthen the Spaghetti's already exhausted stay. Then, when Sartana and Django or Sabata and Halleluja began teaming together (much like in the forties when Universal Studios teamed up Frankenstein, the Wolfman, and Dracula near the end of their run) you knew it was only a matter of time before it all collapsed.

Before the end came, however, such jewels as Lucio Fulci's Four Gunmen of the Apocalypse and Enzo G. Castellari's hauntingly poetic Keoma managed to appear. By the early eighties, the Spaghetti Western had disappeared. Now, some ten years later, Thomas Weisser has performed a marvelous service for a heretofore little appreciated period of filmmaking that featured a depth and imagination every bit as important and interesting as its U.S. counterpart. As videotape exposes more people to the wonder and intensity of these films, their appreciation for this project can only grow.

June 17, 1991

Mr. Ledbetter is editor of E. T. C. Magazine

Foreword

(Tom Betts)

Spaghetti Westerns are remarkable. Watching them, the viewer is immediately captured by the sharp contrast between a European-made Western and an American-made Western.

For starters, Spaghetti Westerns deal primarily with the Mexican border region of the American Southwest. A viewer hears the wind blowing across the hot desert sands. He can feel the heat rising from these same sands, and he is captured by the barren landscape sprawling before him.

The Europeans focused on this part of the American West mostly because of convenience. Usually, the plains of Spain were used for the exterior photography, and this region closely resembles the border area of the United States. Furthermore, the towns are never neatly-erected buildings with fresh coats of paint. Instead, they are crudely constructed, developed from whatever materials could be found close by; or they are "Mexican" adobe and stucco villages.

The Spaghetti directors then created the characters to match this rugged landscape. These are rough men; men who, like the landscape, didn't give an inch. Only the fittest survived in this hell. You can see it in the faces of the Spanish extras, hired to play villagers or bandidos. Their faces are weathered, dried from the sun, often missing teeth or an eye. These are faces that have withstood the test of the land and have survived. It's obvious that these people could only be controlled by raw, brutal strength. And each could be defeated only by a man who was equally strong, but who used his brains to tip the scales in his favor.

Next page