SPAGHETTI WESTERNS: INTRODUCING THE GANG

The storekeeper looked up. Silhouetted in the open doorway stood a man, his face hidden by the lowered brim of his battered Stetson. The stranger paused to take a long drag on the cigar clenched between his teeth, as he slowly raised his head to stare at the proprietor. The storekeeper caught sight of the strangers stubbled, sunburnt face and his piercing, cold eyes. Ominously, with the clink of spurs, the figure walked to the counter. Unnerved, a bead of sweat rolled down the storekeepers brow as he spluttered, What er what can I get you, sir? For a moment, the stranger held his gaze in silence. Then he replied in a low, whispering drawl, Do you have A Bullet for the General or A Pistol for Ringo? The storekeeper looked perplexed. Im sorry We dont sell guns, sir, he answered. This is a DVD shop.

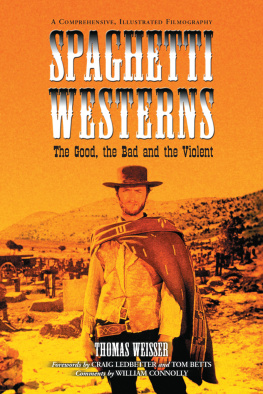

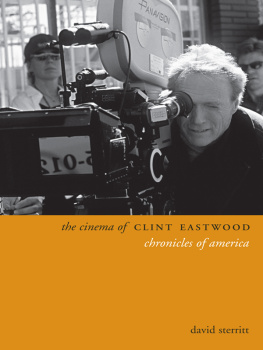

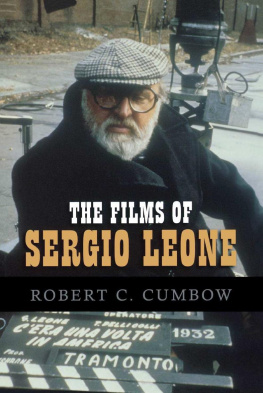

Spaghetti Westerns their style has passed into cinematic folklore, their heroes have become superstars and their influential music has become instantly recognisable. Cool gringos and stone-faced bounty hunters shoot Mexican bandits for fistfuls of dollars, in the bleakest of desert landscapes. Striding way over the line normally called self-parody, Italian-made Spaghetti Westerns are the most enduringly popular genre to have emerged from Cinecitt Film Studios in Rome. Through their mannered style, rejection of Hollywood clichs, influential music, sharp editing and pared-down dialogue they are, with the James Bond movies, the brutal model for sixties action cinema. Cinema and TV audiences the world over are familiar with Clint Eastwoods poncho-clad, cigar-smoking drifter, making his image the enduring symbol of the genre. A man alone (or occasionally in an untrustworthy partnership) facing villains that are irredeemably bad. Eastwood killed with a speed and detachment never seen before on the cinema screen. He was the epitome of cool, a man of few words and even fewer morals, who would sell his gun to the highest bidder in an effort to get rich in a desolate wasteland where dollars meant everything and life meant nothing.

As directed by visionary Italian director Sergio Leone in the plains of Spain, Eastwood became the ultimate anti-hero and their three films together, A Fistful of Dollars (1964), For a Few Dollars More (1965) and The Good , the Bad and the Ugly (1966) dubbed the Dollars Trilogy were hugely successful, making Eastwood the biggest star of his generation and arguably (John Wayne fans would disagree) the most famous movie gunslinger of them all. Leone directed two more Westerns and the runaway success of his movies, in particular the Eastwood films, led to all the other foreign Westerns (between 1961 and 1978 there were 500 made) being universally disregarded as worthless copies. Most of the Italian, German, Spanish and French Westerns made throughout the sixties were rightly labelled junk. But this vast output is now more accessible, due to the films availability on video and DVD, so Western fans can at last make up their own minds. Of the numerous Spaghettis made, there are at least 20 films that deserve the kudos of Leones movies. And there are plenty that were considerably more appealing and contemporary than John Wayne wandering through Texas telling everyone to vote Republican. Because Eastwood became a star, the films directed by Leones cohorts, rivals and, in some cases, friends have been largely ignored in mainstream circles, even though some of their films, particularly the comedy Spaghetti Westerns, went on to make more money than Leones films.

The time has come to set things aright.

EUROPEAN WESTERNS?

Westerns were one of the most popular forms of cinema entertainment ever. Even now, TV schedules are packed with all sorts of Westerns. Many excellent examples had been made in the first part of the twentieth century by masterly practitioners like John Ford, Raoul Walsh and Howard Hawks, but the vast majority were programme fillers, singing-cowboy vehicles (usually accompanied by a horse as a sidekick) and serial Westerns fast, action-filled oaters aimed at the matinee audience. But by the fifties the subtext had deepened, with more thought being given even to the low-budget B-Westerns. Subjects like racism, delinquency, McCarthyism and psychology were often injected into the scenarios. But because of the shear volume of B-Westerns being produced, audiences were getting fed up with the same plots and actors cropping up over and over again. After all, they could get that on TV.

The emergence of the TV Western in the mid-fifties was the death knell of the Hollywood Western. The big cinema hits were super-productions like Ben Hur (1959) and El Cid (1961), giant movies on giant screens, with stars like Charlton Heston and Sophia Loren. If you wanted to see a Western, you tuned in to Gunsmoke , Laramie or Rawhide once a week, to see what Chuck, Hank or Rowdy were up to. Meanwhile, popular Western themes were appearing elsewhere the prime examples being the films of Japanese director Akira Kurosawa. His Seven Samurai (1954) was obviously influenced by classic Hollywood Westerns. For poor peasant farmers read poor settlers, for roving bandits read roving Indians and for Seven Samurai read the Seventh Cavalry. Yojimbo (1961) and Sanjuro (1962) looked even more like Westerns, especially Yojimbo with its windswept ghost town and warring gangs. Stylistically, emotionally and technically these intelligent action movies were way ahead of the field. In 1960, Seven Samurai became the basis for The Magnificent Seven , a hugely successful Western, which made its best box-office returns, not in America, but in Europe.

Curiously, with fewer real Westerns being released, countries that liked Westerns, but werent getting any decent ones, decided to manufacture their own. Rising production costs were one of the deciding factors in reducing the number of American Westerns produced, but costs in Europe were considerably less. Spain was an exceptionally cheap location for making exotic, desert-set action movies. In the late fifties and early sixties the Spanish and British started making Westerns in the sun-scorched landscape of Almeria, Southern Spain. The Americans soon followed suit. It was an irony that it was cheaper to make Westerns in this ersatz West than it was to film them in the real thing.

Even weirder was when the West Germans joined in, using Yugoslavia as the American frontier. German author Karl May was long dead when director Harald Reinl decided to film Mays Winnetou stories in 1962. The series concerned the adventures of a buckskinned adventurer, Old Shatterhand (Lex Barker), and his Tonto-like sidekick, Apache chief Winnetou (Pierre Brice). The series began with the action-packed The Treasure of Silver Lake, with Herbert Lom (from the Inspector Clouseau films) as the villain. Making a killing in Europe, the sequel Winnetou the Warrior (1963) was even more successful. Other notable examples included Last of the Renegades (1964), with Klaus Kinski as a baddie in a coonskin hat, and Among Vultures (1964), with English actor Stewart Granger playing effete Old Surehand. The action sequences were impressively staged and remain the most memorable aspects of the series from massed attacks on forts, towns and Indian villages, burning oil wells and wagon-train massacres, to more unusual action spots like bear wrestling and trains driven through saloons. Martin Bttchers music was suitably epic (with a resonance that sounded like it was recorded in an echo chamber) and the films revitalised hackneyed Western plots something that Hollywood had presumed impossible in the early sixties.