GREATEST

WESTERNS

Also available

The 50 Greatest Road Trips

The 50 Greatest Train Journeys of the World

The 50 Greatest Rugby Union Players of All Time

The 50 Most Influential Britons of the Last 100 Years

The 50 Greatest Walks of the World

Geoff Hursts Greats: Englands 1966 Hero Selects His Finest Ever Footballers

David Gowers Greatest Half-Century

GREATEST

WESTERNS

BARRY STONE

Published in the UK in 2016 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

3941 North Road, London N7 9DP

email:

www.iconbooks.com

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

7477 Great Russell Street,

London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asia

by Grantham Book Services, Trent Road,

Grantham NG31 7XQ

Distributed in Australia and New Zealand

by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd,

PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street,

Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in South Africa by

Jonathan Ball, Office B4, The District,

41 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock 7925

Distributed in India by Penguin Books India,

7th Floor, Infinity Tower C, DLF Cyber City,

Gurgaon 122002, Haryana

Distributed in Canada by Publishers Group Canada,

76 Stafford Street, Unit 300, Toronto, Ontario M6J 2S1

Distributed in the USA by Publishers Group West,

1700 Fourth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710

ISBN: 978-178578-098-1

Text copyright 2016 Barry Stone

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Images see individual pictures

Typeset and designed by Simmons Pugh

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

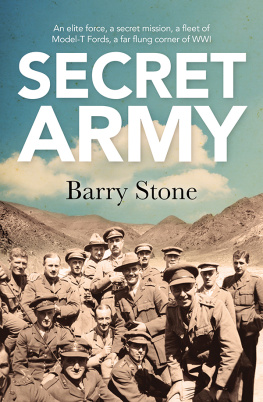

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

B arry Stone is a travel writer and author of eleven non-fiction books covering subjects as diverse as mutinies in the Age of Sail, historic Australian hotels and sporting scandals. His first book, I Want to Be Alone, a historical study of hermits and recluses, has been translated into Standard Chinese.

His affection for western movies, however, long pre-dates all of that. The 50 Greatest Westerns has been a long time coming. A frequent attendee of local and international film festivals and western retrospectives, he now offers up a very personal Best 50 List. He lives in Sydney, Australia.

INTRODUCTION

For my father,

who loved watching westerns with me

and for my friend Dave Card,

who always made me laugh

T he western movie is Americas genre, in the same way that jazz is its music and baseball its sport. More than any other film type, it embodies traits that Americans have always laid claim to, with its central theme of civilisation versus wilderness providing the spark for a young nations energy, inventiveness, persistence and individualism. Audiences everywhere, regardless of whether they lived on the plains or in teeming cities, connected with its themes because the further you wind back the clock of white settlement in the New World, the more youre reminded the entire nation was once one vast, unexplored frontier. In the early 1500s, and for the next two centuries, wilderness was everywhere.

Americas wild west, when it finally did come in the wake of the Civil War, came and went with a rush in just a few decades, a remarkable achievement when you consider it took three hundred years for its fledgling communities along its Atlantic coast just to expand to the eastern banks of the Mississippi River! Little time was lost, too, in mythologising it. Artists like Thomas Cole (Daniel Boone Sitting at the Door of His Cabin on the Great Osage Lake, c.1826), Emanuel Leutze (Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way, 1861) and Albert Bierstadt (Emigrants Crossing the Plains, 1867) painted stylised representations of Eden-like landscapes that, intentionally or not, promoted the idea of Manifest Destiny, the belief that westward expansion at any cost was both inevitable and wholly justified.

In literature the mythology of the west that would one day be taken to undreamt-of levels by Hollywood had its origins in the series of books called the Leatherstocking Tales by James Fenimore Cooper. Written from 1823 to 1841, Cooper popularised the adventures of Natty Bumppo, a young man who spent his youth hunting with the Delaware Indians before living for a time in upstate New York where he watched with dismay its transformation from wilderness to farmland, eventually ending his days an old man on the Great Plains. Now considered American literary classics, Coopers work on the virtues of wilderness and personal freedom saw him contribute more than almost any other single 19th-century American to the creation of an idealised frontier. Long before movie cameras ever began to roll, the west had been mythologised in art and literature, with the nations most iconic landscapes the Rocky Mountains, the Grand Canyon, the prairies already on a descent into the mire of nostalgia. In 1893, three years after the Massacre at Wounded Knee and the end of Native American resistance, the frontier was pronounced officially closed. The wild west was suddenly the stuff of legend. Then, just ten years later, before the dust on it had barely settled, along came Hollywood

The historical west never remained static for long, its growing pains open wounds for all to see: the murder and displacement of its Native Americans, the slaughter to near-extinction of the buffalo, the carving up of the prairies in the wake of the Homestead Act, the greed that came with the Trans-continental Railroad, the lawlessness, the rush for gold and silver. And for this reason we see, too, the evolving nature of the film genre. From The Great Train Robbery of 1903 twelve minutes of oh-so-precious images that contain in its innocence all of the plot lines of the coming 50 years to the arrival of the silent epics The Covered Wagon (1923) and The Iron Horse (1924).

The genres first Mega-star, Tom Mix, appeared in hundreds of feature films from 1909 to 1935 and defined the cowboy persona for a generation. The era of the singing cowboy reached its peak in the late 1930s with actors like Gene Autry and Roy Rogers expressing their emotions through song. In 1939 we saw the fresh-faced Ringo Kid of Stagecoach, a masterpiece that lifted the western into unchartered cinematic territory. After the carnage of the Second World War came the psychological, brooding anti-westerns and impassive heroes of directors Anthony Mann and Budd Boetticher, though by the end of the 1950s and early 1960s, despite or perhaps because of? the popularity of television shows like Gunsmoke and Wagon Train, western cinema audiences were dwindling. Yet they refused to lie down. Whenever a eulogy over the demise of the western was trotted out by film critics who should have known better, the western would reinvent itself and charge back like the proverbial cavalry: The Wild Bunch; Unforgiven; Django Unchained

Sub-genres came along too, to remind us that the western could be far more than we ever imagined it could be. The spaghetti westerns of the 1960s began with a series of overlooked Italian/Spanish co-productions until Sergio Leones

Next page