THE FILMS OF SAM PECKINPAH

NEIL FULWOOD

FOR

MICHAEL EATON

First published in the United Kingdom as an eBook in 2014 by

Batsford

1 Gower Street

London WC1E 6HD

An imprint of Pavilion Books Company Ltd

www.batsford.com

Copyright Batsford

Text Neil Fulwood 2002

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

eBook ISBN: 978-184994-254-6

CONTENTS

FILMOGRAPHY

TELEVISION

The Rifleman series (195859). Story consultant on the first series. The episodes listed are those he wrote, co-wrote or directed: The Marshall, The Home Ranch, The Boarding House, The Money Gun, The Babysitter.

The Westerner series (1960). Producer. Jeff, School Day, Brown, Mrs Kennedy, Dos Pinos, The Courting of Libby, The Treasure, The Old Man, Ghost of a Chance, The Line Camp, Going Home, Hand on the Gun, The Painting.

Dick Powells Zane Grey Theater (1959). Director. Trouble at Treces Cruces (the pilot episode for The Westerner), Miss Jenny, Lonesome Road.

The Dick Powell Theater (1962). Director. Pericles on 31st Street, The Losers.

ABC Stage 67 (1966). Director. Noon Wine.

Bob Hopes Chrysler Theater (1966). Director. That Lady is My Wife.

FILM

The Deadly Companions (1961).

Ride the High Country, a.k.a. Guns in the Afternoon (1962).

Major Dundee (1965).

The Wild Bunch (1969).

The Ballad of Cable Hogue (1970).

Straw Dogs, a.k.a. Sam Peckinpahs Straw Dogs (1971).

Junior Bonner (1971).

The Getaway (1972).

Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973).

Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974).

The Killer Elite (1915).

Cross of Iron (1977).

Convoy (1978).

The Osterman Weekend (1983).

MUSIC VIDEO

Julian Lennon, Valotte, Too Late for Goodbyes (both 1984).

INTRODUCTION

BLOODY SAM

Its an unfair epithet, conjured up by critics who mistakenly thought he was no more than a director with a flair for violence. He was considerably more complex than that. Moralistic but not judgmental, tough but vulnerable, sensitive but stubborn. His sense of artistic integrity flew in the face of commercialism. Pressured to reduce the depth and thematic density of his work by studio executives who answered to the dollar, he stuck to his guns. As a result, he was removed from projects, locked out of post-production, his preferred cuts butchered. Almost every film he made was subject to interference. But damned if he didnt fight for his artistic vision.

Bloody Sam? Bloody-minded Sam, more like.

Its said that life imitates art. His life and art merged from the start. Whatever line might have been drawn between events behind the camera and the vision he forged in front of it, by the end that line had been worn away by booze and cocaine and a life spent living it like he told it.

Sam Peckinpah made films about men. Men who ride together. And he made them in collaboration with men whose loyalty to him was unchallenged. Actors Warren Oates, L Q Jones, Strother Martin, John Davis Chandler, R G Armstrong, Dub Taylor, Ben Johnson and Slim Pickens, cinematographers Lucien Ballard and John Coquillon, composer Jerry Fielding, editors Louis Lombardo, Robert L Wolfe and Roger Spottiswoode. They were his posse and he the last outlaw, a renegade, a desperado, outliving his time even as he cut a swathe through Hollywood, redefining the way that films would be made.

Maverick that he was, star names would be drawn back to him: James Coburn, David Warner and Kris Kristofferson each notch up three appearances in Peckinpah films, Steve McQueen and Ernest Borgnine two apiece. Even actors who only worked with him the once William Holden, Robert Ryan, Dustin Hoffman, Al Lettieri, Stella Stevens, Susan George give tour de force performances that it can be argued remain unmatched by anything else in their respective filmographies.

Part of Peckinpahs genius was that he could tap into other peoples talent. Take Lucien Ballard. Outside of Sams oeuvre, he lensed somewhere in the region of one hundred films, including The Parent Trap, Hour of the Gun, the Elvis Presley vehicle Roustabout, and Breakheart Pass. Undistinguished, all. The best that can be said is that they are nice looking. But on Ride the High Country, The Wild Bunch and The Ballad of Cable Hogue, his technical ability and eye for composition, allayed with Peckinpahs artistic vision and poets soul, transcended nice visuals and took cinematography into the realms of art. Coquillon, too: Michael Reevess Witchfinder General(1) was perhaps the only non-Peckinpah project he worked on that demonstrated the clarity of vision of Straw Dogs, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid and Cross of Iron.

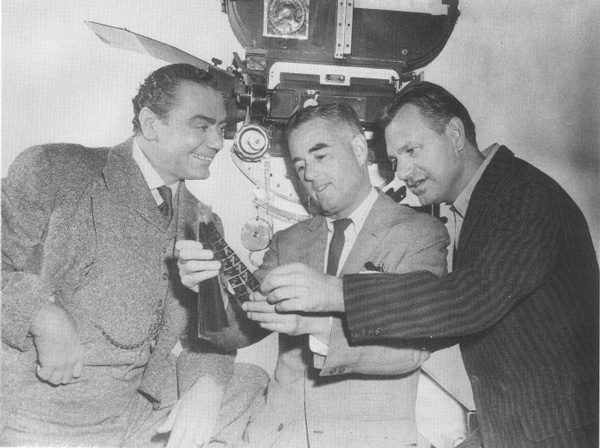

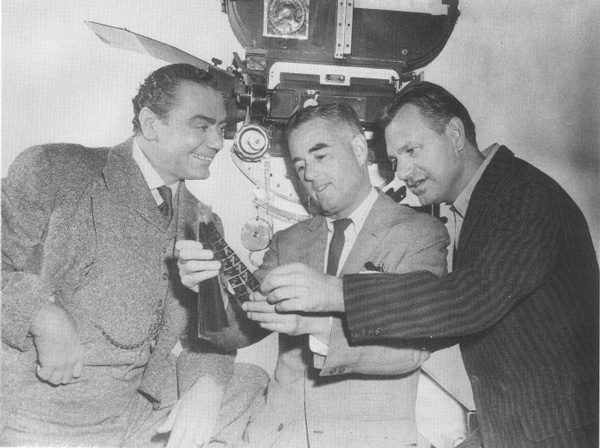

Cinematographer Lucien Ballard, pictured here with Ernest Borgnine on Ride the High Country they would work together again on The Wild Bunch.

Technical accomplishment and verisimilitude of acting are only part of what sets Peckinpahs films apart. It is their depth and intensity that make them unique. And if what Peckinpah put on screen is breath-taking, the off-camera excesses that made it possible are just as remarkable. The crazed journey into Mexico undertaken by the ramshackle cavalry outfit in Major Dundee approximates that made by cast and crew. The horror stories that surrounded the production arduous location shooting, haemorrhaging budget, demonically driven director precede accounts of the equally lunatic leadership on Francis Ford Coppolas Apocalypse Now and Werner Herzogs Fitzcarraldo by more than a decade.

Giving direction to Oates, Jones, Chandler, James Drury and John Anderson, who play the Hammond brothers, the antagonists of Ride the High Country, he ordered them to stay apart from the rest of the cast and crew, and to drink and brawl together in order to find the characters internal dynamic. A decade later, he applied the same technique on Straw Dogs, encouraging fights and bouts of wrestling. During shooting, T P McKenna suffered a broken arm, and production was shut down for five days when Peckinpah was hospitalised with pneumonia following a marathon drinking session with Ken Hutchinson which ended with them out at Lands End in the early hours of the morning, in the middle of a storm, singing drunkenly.

Or how about his relationship with Warren Oates? Given an ultimatum by his then wife not to accept a role in The Wild Bunch because of the ill-health hed suffered during his previous collaboration with Peckinpah, Major Dundee, Oates made the choice between his marriage and his mentor without hesitation. He went to Mexico with Sam, made one of the greatest movies of all time, and got divorced.

Peckinpahs life away from film-making (such as it was his need to express himself creatively on the largest possible canvas, the big screen, was overwhelming and all-encompassing; not just a need, but a raison dtre) was often troubled and destructive. It is no coincidence that when his heroes are not indulging in what is today referred to, rather wimpily, as male bonding, they are contemplating a lonelier perspective: the mistakes they have made, the chances they have passed up, the failure of love. In

Next page