Foreword

by Michael Feinstein

It takes many things to make a movie musical. Money, of course, but also much that cannot carry a price tag: imagination, ingenuity, audacity, wisdom, experience, creativity, energy, courage. Most of all, it takes talent, which can manifest itself in all sorts of ways. There are the inherent and intuitive gifts of a great artist, the learned skills of a master technician, and everything in between. Without an abundance of talent in every department and category, a musical film will never fly, let alone become one that can carry the label Must-See. Yet, despite these staggering requirements and achievements, it must be noted that during the so-called Golden Age of the Movie Musicalroughly the mid-1930s to the mid-1950stalent was often, if not usually, taken for granted. With a studio such as MGM, in its busiest years turning out one feature film per week, those in charge could rule over even the most exceptionally gifted employees with a factory mindset. Those who worked both before and behind the camera were contracted, salaried, and often unappreciated, producing work which far too often was accepted but not necessarily prized. Andre Previn, who began working at MGM while still in his teens, commented on this situation very pointedly. From the perspective of the studio bosses, he said, the music department was no more or less important than the department of fake lawns.

Fortunately, the artists themselves did not feel that way toward their work. They took pride in what they did, and the films they made gloriously demonstrate that this pride was very much justified. Its only in retrospect, in fact, that we can now fully appreciate the magnitude of talent that went into creating the greatest musicals. It should be stressed, too, that this talent was not borne only by the biggest names in the movie credits, by the Astaires and Garlands and Kellys and Days. Other people working in musicals may have had far less name recognition, but possessed equal gifts. My particular heroes in musicals have names that are unknown to most viewers, since the results of their specific genius were heard, not seen. Composers, orchestrators, conductors, and arrangers such as Roger Edens, Conrad Salinger, Herbert Spencer, Skip Martin, Kay Thompson, David Raksin, Saul Chaplin, Lennie Hayton, and Edward Powell are, for me, the invisible giants who have informed the sensibility I have in approaching music. I will always be grateful to them, and for them.

Just about all of the best musical films have something in common: their greatness is more apparent now than was the case when they were new. As perspective makes clear, these movies are far from frivolous, and vastly more substantial than originally thought. Even now, they dont always get the respect they deserve, yet nonetheless have an effect which can be profound. By using a sort of fantasy kaleidoscope, they reflect societys dreams, ideals, and yearnings, capturing an honesty that is tremendously genuine. A film such as The Band Wagon uses a vast amount of artistry and spectacle, in both sight and sound, to say things which are, at the heart of the matter, personal and meaningful. The extraordinary quality of the work on display might make it easy to momentarily forget that were being told fundamental human truths, but they come through regardless.

Especially in these times of devalued appreciation for art in general, musicals will continue to be significant, to inspire wonder and devotion in each succeeding generation. Best of all, these generations will then be moved to create fresh and outstanding work. So it is that Must-See Musicals, old and new, will keep on going. They are, in a magnificent kind of way, eternal.

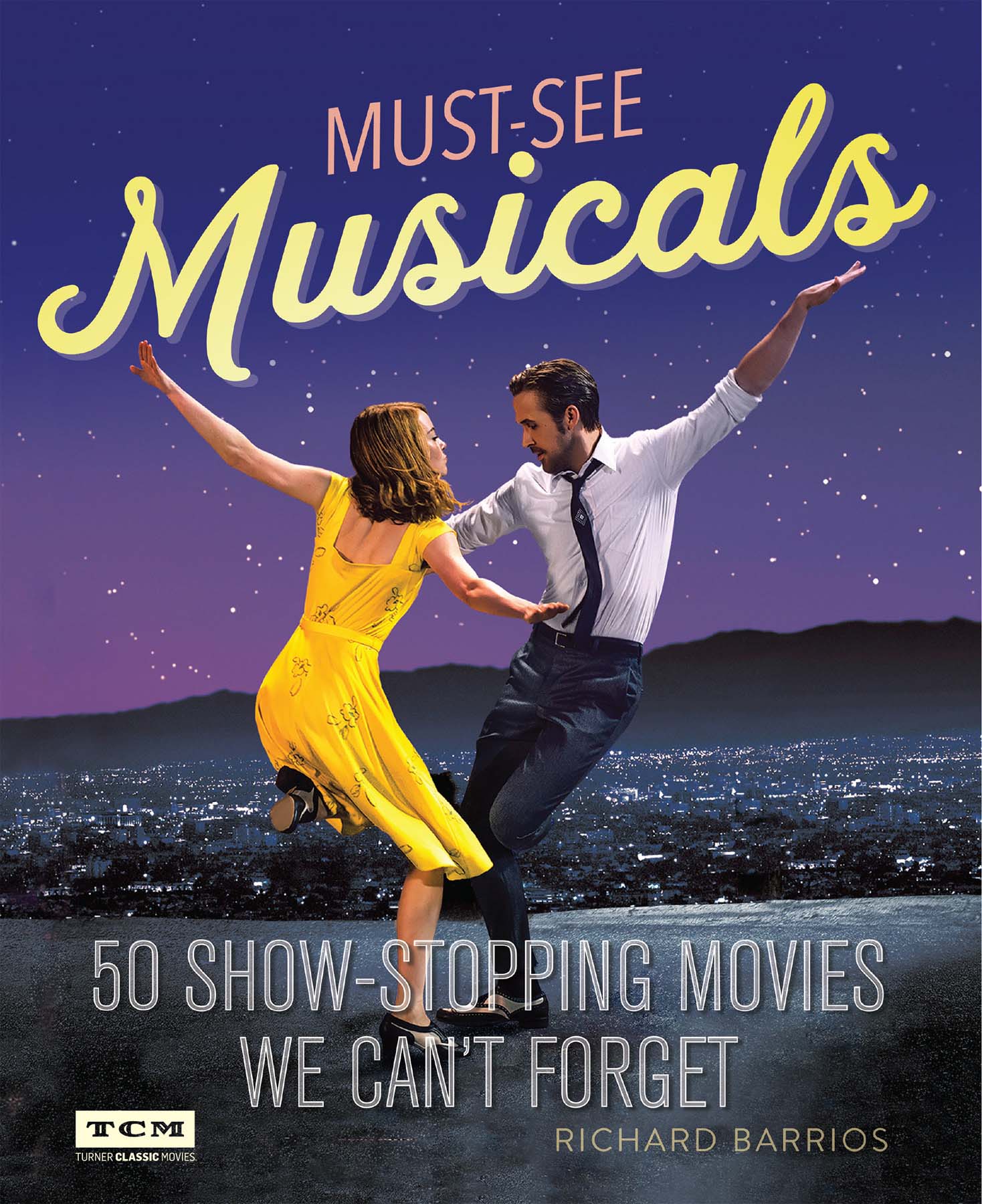

A man so elated that he sings and dances through a downpour. A girl with a dog, wondering about life beyond her Kansas farm. A painted master of ceremonies in a sinister cabaret. A young woman who isnt cut out to be a nun. A pair of murderesses who wow the crowds as they strut while waving machine guns. A couple in Los Angeles who might fall in love while they dance. Chorus line formations, dancing gang members, and Americans in Paris.

These are all memorable images, and the sounds that accompany them are equally unforgettable. They are, of course, just a few moments from a fabulous and fascinatingif sometimes peculiarbody of work we call movie musicals. For the millions who care about them, musicals are like comfort food without the calories and intoxication without the hangover. They can turn depression into joy and burdens into blessings, and the pleasure they offer usually contains no guilt. They imply that dreams can come true or are at least reasonable, and hold the possibility that perhaps we too can express our feelings by dancing like Astaire or singing like Streisand.

Musicals are special, too, in that not everyone appreciates them, nor understands those who do. In fact, one reason they have gone in and out of fashion so often is because it takes a particular, and not always prevalent, mind-set to comprehend and embrace them. But dont ever count them out; every single time people think theyre over, a new song-and-dance phoenix will rise to show just how resilient they can be, and how wonderful.

From the late 1920s to now and beyond, musical films have been extraordinarily adept at communicating with their audiences and connecting them with both current tastes and timeless aspirations. In their nine decades of existence, they have been indelible and necessary, and scores of them are classicsalthough perhaps that word scores needs examination. It may be that the musical best of the best, the collection of titles that are truly great, is not as large a group as one might imagine. Lots of them have one or two wonderful numbers or scenes but also a great deal of uninspired filler. There are many where the script is not nearly as compelling as the music, and some where good intentions were followed by dismaying results. It takes enormous effort to produce a musical that is genuinely good in its entirety, and, of course, theres that built-in proviso under which every musical must operate: the harder it works, the easier it must make it all seem. They take an enormous amount of preparation and engineering, and for the most part must disguise all of it in a brightly colored haze of effortlessness. For one to sustain its quality all the way through to the end, in the manner of, say, a