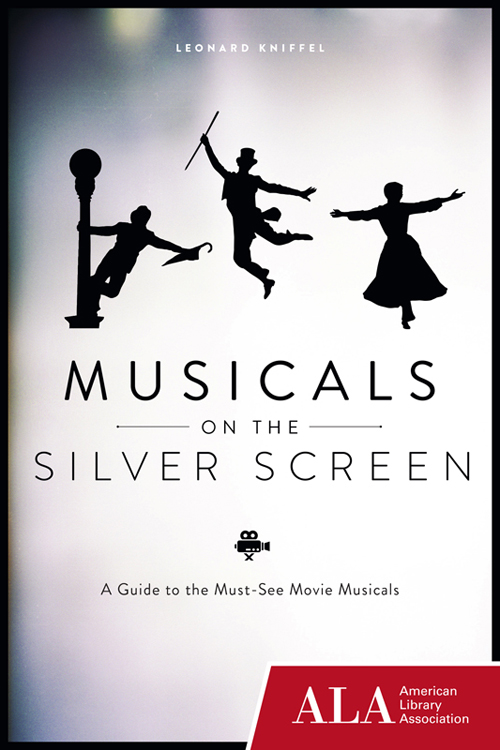

Huron Street Press proceeds support the American Library Association in its mission to provide leadership for the development, promotion, and improvement of library and information services and the profession of librarianship in order to enhance learning and ensure access to information for all.

LEONARD KNIFFEL is a writer and librarian living in Chicago. He was editor and publisher of American Libraries, the magazine of the American Library Association, from 1996 to 2012. A lifelong fan of movie musicals, he is also the author of Reading with the Stars: A Celebration of Books and Libraries (American Library Association and Skyhorse Publishing, 2011) and A Polish Son in the Motherland: An Americans Journey Home (Texas A&M University Press, 2005), a travel memoir.

2013 by the American Library Association. Any claim of copyright is subject to applicable limitations and exceptions, such as rights of fair use and library copying pursuant to Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Act. No copyright is claimed for content in the public domain, such as works of the U.S. government.

Published by Huron Street Press, an imprint of ALA Publishing

Extensive effort has gone into ensuring the reliability of the information in this book; however, the publisher makes no warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein.

ISBNs: 978-1-937589-30-1 (paper); 978-1-937589-48-6 (PDF). For more information on digital formats, visit the ALA Store at alastore.ala.org and select eEditions.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kniffel, Leonard.

Musicals on the silver screen / Leonard Kniffel.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-937589-30-1 (alk. paper); 978-1-937589-52-3 (ePub); 978-1-937589-53-0 (Kindle)

1. Musical filmsUnited StatesHistory and criticism. I. Title.

PN1995.9.M86K56 2013

791.43'6dc23 2013005832

In memory of my godmother, Helen Gutt Brodacki Riley, and her beautiful voice

Contents

When I first started writing musicals in the late 1980s, the Internet was in its infancy. You couldnt stream a video, let alone find clips of your favorite musicals on YouTube, which wouldnt come into existence for more than a decade. At that time, for inspiration and to feed my insatiable musical theater addiction, I used to borrow films of classic musicals from the Chicago Public Library, if it had them, or from Facets Multimedia, an art film cinema-bibliothque in Lincoln Park, just around the corner from my apartment at the time. To this day, I remember the thrill of seeing for the first time the hallucinogenic choreography of I Only Have Eyes for You in Busby Berkeleys film Dames. Eureka! Suddenly I had discovered what the American musical was all abouta lot of song, a little sap, and a big dose of tap.

Had I had then a copy of Leonard Kniffels book Musicals on the Silver Screen, I would have been in serious dangerdanger of never leaving my apartment. Kniffels book is an invaluable resource and, ironically, much as it would have come in handy to me back in the 80s, its even more timely now. With the advent of Amazon.com, online streaming video, and YouTube, its a lot easier to find some of the rare and arcane gems that Kniffel discusses in his book.

Musicals on the Silver Screen is nothing short of encyclopedic in its scope. And unlike most invaluable reference books, its downright entertaining. Beginning with the first talkie, The Jazz Singer (1927), Kniffel takes us on a chronological odyssey that ends, appropriately, with 2011s The Artist. Within the scope of those eighty-four years, Kniffel brings us all the important (and, hes the first to admit, some not-so-important) musicals of the decade.

His commentaries on each film are necessarily short, but they contain all the vital information. They are replete with his smart takes on the changing social attitudes of the films as well as being larded with fascinating stories of the stars themselves. Heres Kniffels perceptive insight on The Jazz Singer: Its ironic that the first sound musical featured a white Jew imitating African American performance style for a primarily WASP audience. Often he interjects an interesting tidbit of cinematic lore, such as how the silver screen got its name. Im not going to tell you thatyoull have to read the book to find out.

Its hard to imagine what fell through the floorboards in Musicals on the Silver Screen. The sheer number of films discussedwhich Kniffel has viewed and gives thumbnail reviews ofis gargantuan.

As far as I can make out, theres only one thing wrong with this bookit doesnt come with a large bucket of popcorn.

Gregg Opelka

Movie Musicals and Their Stars

My love affair with movie musicals began when I was eleven years old. Thats when we got our first television. On school days I would sneak out of bed to watch movies late into the night. On weekends I could hardly wait for Saturday Night at the Movies, hoping the television premiere that week would be a musical. You could not borrow movies from the public library in those days, nor could you buy them or download them for your home library.

When movies began to talk in 1927, my mother was eight years old and would not enter a movie theater for another ten years. This may explain why at our house motion pictures always seemed as magical as the airplane, the telephone, electricity, and indoor plumbing.

When I was in high school, I did not realize when we took class trips to theaters in downtown Detroit to see West Side Story and The Sound of Music that I was living through a golden age of film musicals.

What I loved about musicals as a young adult is the way they transported me away from our farm to worlds that I never imagined or thought I would never see. You could be vicariously an American in Paris, a nun in the Alps, or a visitor in the merry old land of Oz. It was also possible through musicals to live in a world where men sang and danced and joked together instead of fighting and killing one another. Even as you watch West Side Story, with its gang warfare and ethnic hatred, you are aware that the fights and murders are being staged as an excuse to sing and dance. At the end of West Side Story, The King and I, and even The Music Man, it is uplifting to see ego, greed, jealousy, and rage defeated by a song.

The preferences you develop and favorites you have as a young adult stay with you forever. Judy Garland was the most mesmerizing performer I had ever seen. Something about her led me to all the rest of the stars of the 1940s, and I was mistakenly convinced that I was the only teenager in the rural Midwest who appreciated Judy Garland. I still like the athletic Gene Kelly a bit better than the debonair Fred Astaire. I prefer the Doris Day-type heroine who brought out the best in her man (Young at Heart) over the Debbie Reynolds schemer gal, who was often trying to trick a man (Singin in the Rain). Then there was adorable Shirley Temple, who sang and danced in almost all of her films. She can still stop me in my tracks when I see her on the screen.

It was long after my musical preferences were set that I learned that certain singers voices were dubbed in filmsusually the womens. Both Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly had rather thin voices, but to my knowledge they were never dubbed. Audrey Hepburns singing in

Next page