Published in 2003 by

Routledge

711 Third Avenue,

New York, NY 10017

www.routledge-ny.com

Published in Great Britain by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park,

Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

www.routledge.co.uk

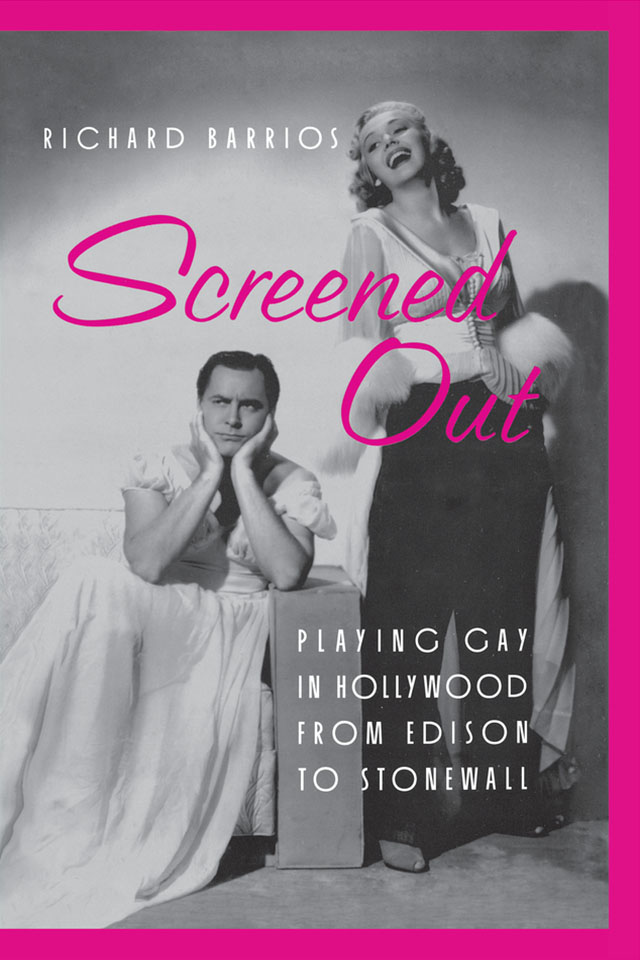

Copyright 2003 by Richard Barrios

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Barrios, Richard.

Screened out: playing gay in Hollywood from Edison to Stonewall / Richard John Barrios.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN: 978-0-415-92328-6

1. Homosexuality in motion pictures. I. Title.

PN1995.9.H55 B37 2002

791.43'653dc21

2002004760

It is perhaps fitting that this book, which examines a rather strange course of history, had its own peculiar evolution. Delays and digressions of all manner came with unsettling frequency, and the elements of writer's block became, ultimately, all too apparent and familiar. Perhaps, at some point, the odd odyssey of Screened Out may in fact warrant its own book, no doubt in a genre poised somewhere between slapstick comedy and existential horror. In any case it was, somehow, eventually completed, albeit far behind schedule. When I was finally able to take a breather and look back, I was stunned by the number of people who had helped me and supported the creation of this work. I can only extend my heartfelt thanks to all of them.

First off, I would like to give both gratitude and homage to all the women and men who gave me something to write about, those whose work made mine possible. The directors, writers, actors, technicians, and various others were often brave, frequently audacious, sometimes remarkably talented, and always, always interesting. Even the purported villains of this piecethe bluenoses and obstructionists and bigotsdeserve thanks, for without them there would have been no struggle, no conflict, no sense of ultimate endurance. So to the Pangborns and Mineos, the Mackaills and Emersons, the Cukors and Premingers, and, yes, to all those cranky Breens: you made the historyI only wrote about it.

I must pay special tribute to those custodians of the history I've written about. To the film companies who have taken sufficient care of often forgotten old films, to the archives that preserve them, and to the various companies that have made them available on television and on home video, my gratitude, plus the hope that you are compensated so abundantly that you can make more of these films accessible. My warmest thanks as well to Turner Entertainment, especially to Richard May, who has done so much to let us see our past as reflected in our movies. Bravo Turner Classic Movies! I am grateful as well to the George Eastman House and the Museum of Modern Art for their ongoing efforts in preserving and exhibiting forgotten film. And special applause to the UCLA Film and Television Archive and its valiant, masterful preservation officer Robert Gitt: they have fought long and hard to bring film back from abysses of obscurity and disintegration, and without them we would be staring, all too often, at blank screens.

To anyone reading this book it will be clear that my work was made possible by the preservation of some fascinating documents from the movie pastscripts, studio correspondence, and especially that comedy-horror show, the Hays Office, more formally the Production Code Administration or Motion Picture Association of America. Two archives in particular were; indispensable in this regard. The Cinema-Television Library at the University of Southern California is a combination of warehouse and treasure trove for the film historian. Among its collections are huge groups of scripts and correspondence related to films produced by MGM, Fox and 20th Century-Fox, Universal, and Warner Bros. For me, as for countless other writers and historians, Ned Comstock has been a tireless guide to many of the wonders of that collection. My thanks also to Noelle Carter and the rest of the staff. The Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences contains an equally vast array of material. So vast, in fact, that it would probably take a book just to begin to detail its amazing holdings. For this book the prime source at the Herrick Library was the lovingly preserved papers of the Production Code Administration/Motion Picture Association of American, more familiarly the Hays Office. For anyone interested in the history of morality in the mid-twentieth century, the PCA files might be a good place to start. That ace research archivist Barbara Hall worked tirelessly to help me on my journey through the mazes of Breen and Hays-related correspondence. She also gave some inspired suggestions and was instrumental in helping me to find some crucial script pieces for the 1959 Ben-Hur. Thanks to the rest of the Herrick's able staff as well, particularly Jennifer Peterson, and to researcher Irene Liberatore for her first-rate assistance.

The Bobst Library at New York University has a remarkable microfilm collection as well as other exceptional holdings. I would also like to thank the New York Public Library at Lincoln Center, although most of its Performing Arts collection was unavailable during the time this book was being researched and written; all to a good cause, however, for the newly renovated library is now an even better resource. Thanks also to the Museum of Modern Art Film Library, the Library of Congress, the UCLA Library, the George Eastman House, the Society for Cinephiles, and the American Museum of the Moving Image (Astoria, Queens). Another invaluable resource that needs to be mentioned is the Internet Movie Database (www.imdb.com), a marvelously cross-referenced collection of screen credits and much else.

It was a conscious choice, in writing this history, to rely far more on historical documents than on the memories and reminiscences of participants. Some of those have been recorded elsewhere (and have been employed here); in many cases, the "secretive" nature of the subject, and the long-ago time involved, meant that there were few resources left, few living memories left to plumb. Therefore, I decided that I would let the prime sources be the films themselves and the recorded vestiges of their creation and reception that remain to us. I did, however, interview a large number of men and women for their impressions and memories surrounding encounters, especially long-ago ones, with gays and lesbians on film. To all of them, a heartfelt thank-you.