Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

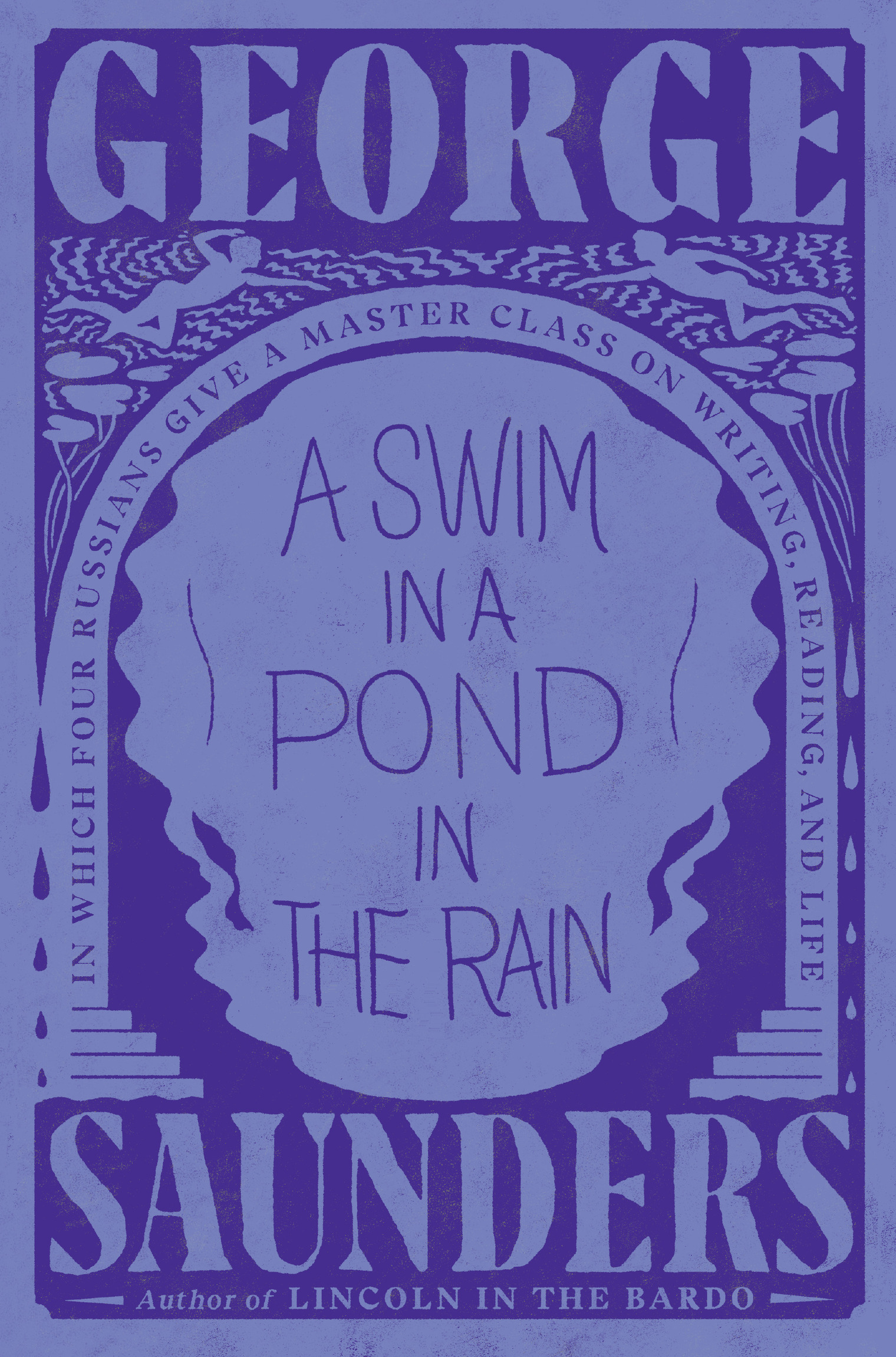

Copyright 2021 by George Saunders

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Random House and the House colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Images on copyright 2021 by Chelsea Cardinal

Text permission credits are located on .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Saunders, George, author. | Gogol, Nikola Vasilevich, 18091852. Nos. English (Struve) | Chekhov, Anton Pavlovich, 18601904. Kryzhovnik. English (Yarmolinsky) | Chekhov, Anton Pavlovich, 18601904. Na podvode. English (Yarmolinsky) | Chekhov, Anton Pavlovich, 18601904. Dushechka. English (Yarmolinsky) | Turgenev, Ivan Sergeevich, 18181883.  . English (Magarshack) | Tolstoy, Leo, graf, 18281910. Alsha Gorshok. English (Brown) | Tolstoy, Leo, graf, 18281910.

. English (Magarshack) | Tolstoy, Leo, graf, 18281910. Alsha Gorshok. English (Brown) | Tolstoy, Leo, graf, 18281910.  i rabotnik. English (Maude and Maude)

i rabotnik. English (Maude and Maude)

Title: A swim in a pond in the rain: in which four Russians give a master class on writing, reading, and life / by George Saunders.

Description: New York: Random House, 2021. | Includes texts of seven short stories. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: lccn 2020031045 (print) | lccn 2020031046 (ebook) | isbn 9781984856029 (hardcover) | isbn 9781984856043 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Gogol, Nikola Vasilevich, 18091852. Nos. | Chekhov, Anton Pavlovich, 18601904. Kryzhovnik. | Chekhov, Anton Pavlovich, 18601904. Na podvode. | Chekhov, Anton Pavlovich, 18601904. Dushechka. | Turgenev, Ivan Sergeevich, 18181883.  . | Tolstoy, Leo, graf, 18281910. Alsha Gorshok. | Tolstoy, Leo, graf, 18281910.

. | Tolstoy, Leo, graf, 18281910. Alsha Gorshok. | Tolstoy, Leo, graf, 18281910.  i rabotnik. | Short stories, Russian19th centuryHistory and criticism. | Short stories, Russian19th centuryHistory and criticismStudy and teaching. | Reader-response criticismUnited States.

i rabotnik. | Short stories, Russian19th centuryHistory and criticism. | Short stories, Russian19th centuryHistory and criticismStudy and teaching. | Reader-response criticismUnited States.

Classification: lcc pg 3097 . s 28 2021 (print) | lcc pg 3097 (ebook) | ddc 891.708dc23

LC record available at lccn.loc.gov/2020031045

LC ebook record available at lccn.loc.gov/2020031046

Ebook ISBN9781984856043

randomhousebooks.com

Book design by Simon M. Sullivan, adapted for ebook

Cover design and illustration: Chelsea Cardinal

ep_prh_5.6.1_c0_r0

Contents

Ivan Ivanych came out of the cabin, plunged into the water with a splash and swam in the rain, thrusting his arms out wide; he raised waves on which white lilies swayed. He swam out to the middle of the river and dived and a minute later came up in another spot and swam on and kept diving, trying to touch bottom. By God! he kept repeating delightedly, by God! He swam to the mill, spoke to the peasants there, and turned back and in the middle of the river lay floating, exposing his face to the rain. Burkin and Alyohin were already dressed and ready to leave, but he kept on swimming and diving. By God! he kept exclaiming, Lord, have mercy on me.

Youve had enough! Burkin shouted to him.

Anton Chekhov , Gooseberries

We Begin

For the last twenty years, at Syracuse University, Ive been teaching a class in the nineteenth-century Russian short story in translation. My students are some of the best young writers in America. (We pick six new students a year from an applicant pool of between six and seven hundred.) They arrive already wonderful. What we try to do over the next three years is help them achieve what I call their iconic spacethe place from which they will write the stories only they could write, using what makes them uniquely themselvestheir strengths, weaknesses, obsessions, peculiarities, the whole deal. At this level, good writing is assumed; the goal is to help them acquire the technical means to become defiantly and joyfully themselves.

In the Russian class, hoping to understand the physics of the form (How does this thing work, anyway?), we turn to a handful of the great Russian writers to see how they did it. I sometimes joke (and yet not) that were reading to see what we can steal.

A few years back, after class (chalk dust hovering in the autumnal air, old-fashioned radiator clanking in the corner, marching band practicing somewhere in the distance, lets say), I had the realization that some of the best moments of my life, the moments during which Ive really felt myself offering something of value to the world, have been spent teaching that Russian class. The stories I teach in it are constantly with me as I work, the high bar against which I measure my own. (I want my stories to move and change someone as much as these Russian stories have moved and changed me.) After all these years, the texts feel like old friends, friends I get to introduce to a new group of brilliant young writers every time I teach the class.

So I decided to write this book, to put some of what my students and I have discovered together over the years down on paper and, in that way, offer a modest version of that class to you.

Over an actual semester we might read thirty stories (two or three per class), but for the purposes of this book well limit ourselves to seven. The stories Ive chosen arent meant to represent a diverse cast of Russian writers (just Chekhov, Turgenev, Tolstoy, and Gogol) or even necessarily the best stories by these writers. Theyre just seven stories I love and have found eminently teachable over the years. If my goal was to get a non-reader to fall in love with the short story, these are among the stories Id offer her. Theyre great stories, in my opinion, written during a high-water period for the form. But theyre not all equally great. Some are great in spite of certain flaws. Some are great because of their flaws. Some of them may require me to do a little convincing (which Im happy to attempt). What I really want to talk about is the short story form itself, and these are good stories for that purpose: simple, clear, elemental.

For a young writer, reading the Russian stories of this period is akin to a young composer studying Bach. All of the bedrock principles of the form are on display. The stories are simple but moving. We care about what happens in them. They were written to challenge and antagonize and outrage. And, in a complicated way, to console.

Once we begin reading the stories, which are, for the most part, quiet, domestic, and apolitical, this idea may strike you as strange; but this is a resistance literature, written by progressive reformers in a repressive culture, under constant threat of censorship, in a time when a writers politics could lead to exile, imprisonment, and execution. The resistance in the stories is quiet, at a slant, and comes from perhaps the most radical idea of all: that every human being is worthy of attention and that the origins of every good and evil capability of the universe may be found by observing a single, even very humble, person and the turnings of his or her mind.

. English (Magarshack) | Tolstoy, Leo, graf, 18281910. Alsha Gorshok. English (Brown) | Tolstoy, Leo, graf, 18281910.

. English (Magarshack) | Tolstoy, Leo, graf, 18281910. Alsha Gorshok. English (Brown) | Tolstoy, Leo, graf, 18281910.  i rabotnik. English (Maude and Maude)

i rabotnik. English (Maude and Maude) . | Tolstoy, Leo, graf, 18281910. Alsha Gorshok. | Tolstoy, Leo, graf, 18281910.

. | Tolstoy, Leo, graf, 18281910. Alsha Gorshok. | Tolstoy, Leo, graf, 18281910.  i rabotnik. | Short stories, Russian19th centuryHistory and criticism. | Short stories, Russian19th centuryHistory and criticismStudy and teaching. | Reader-response criticismUnited States.

i rabotnik. | Short stories, Russian19th centuryHistory and criticism. | Short stories, Russian19th centuryHistory and criticismStudy and teaching. | Reader-response criticismUnited States.