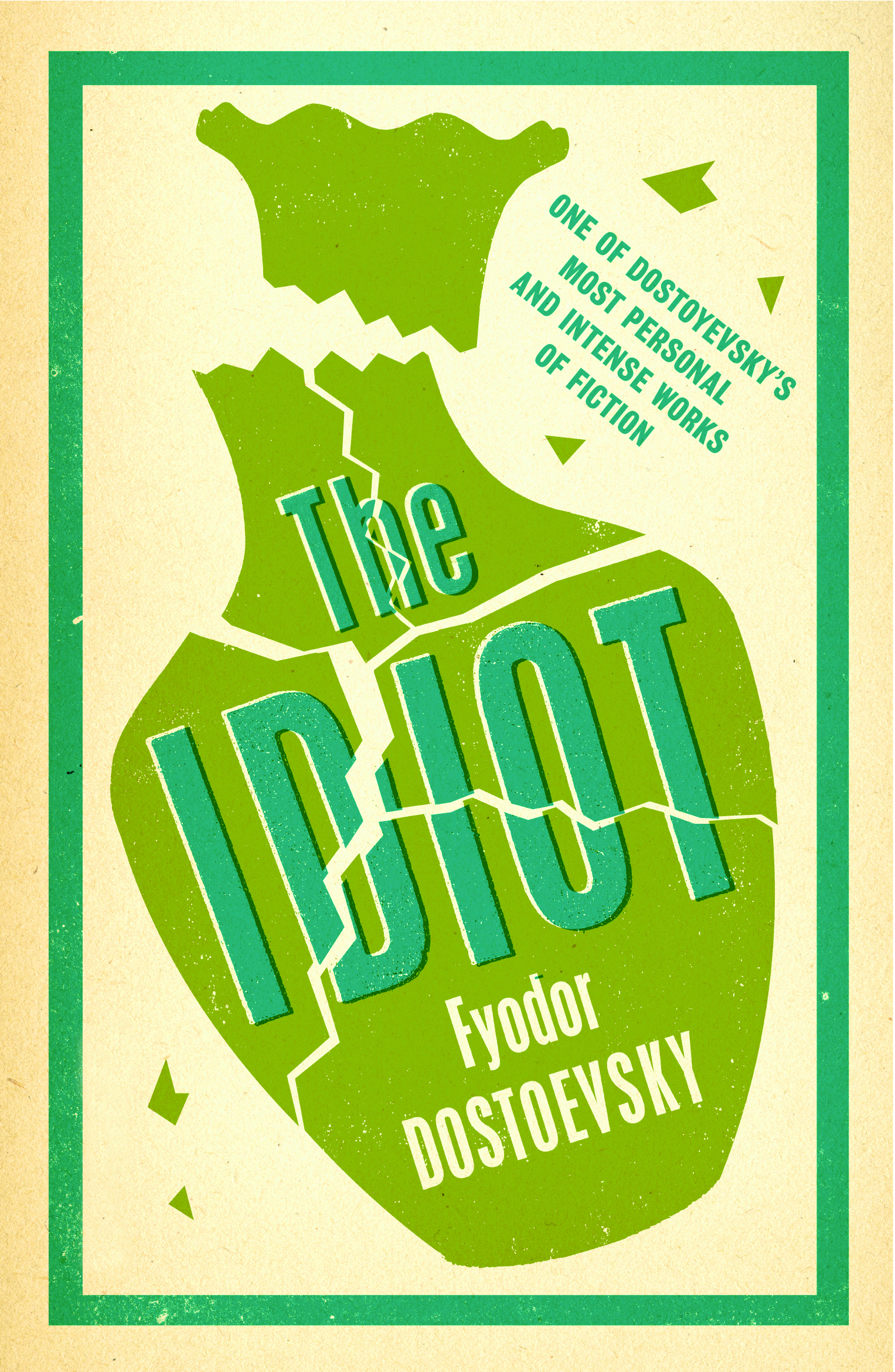

Dostoevsky - The Idiot

Here you can read online Dostoevsky - The Idiot full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2010, publisher: Alma Books, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Idiot

- Author:

- Publisher:Alma Books

- Genre:

- Year:2010

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Idiot: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Idiot" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Idiot — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Idiot" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Idiot

The real nineteenth-century prophet was

Dostoevsky, not Karl Marx.

Albert Camus

Dostoevsky gives me more than any

scientist, more than Gauss!

Albert Einstein

The only psychologist from whom I

have anything to learn.

Friedrich Nietzsche

The novels of Dostoevsky are seething whirlpools,

gyrating sandstorms, waterspouts which hiss and boil

and suck us in. They are composed purely and wholly

of the stuff of the soul. Against our wills we are drawn in,

whirled round, blinded, suffocated, and at the same

time filled with a giddy rapture. Out of Shakespeare

there is no more exciting reading.

Virginia Woolf

The Idiot

Fyodor Dostoevsky

ALMA CLASSICS

alma classics ltd

London House

243-253 Lower Mortlake Road

Richmond

Surrey TW9 2LL

United Kingdom

www.almaclassics.com

The Idiot first published in 1869

This translation first published by Alma Classics Limited (previously Oneworld Classics Ltd) in 2010

This new edition first published by Alma Classics Limited in 2014

Translation, Apparatus and Notes Ignat Avsey, 2010

Cover nathanburtondesign.com

Printed in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

isbn : 978-1-84749-343-9

All the pictures in this volume are reprinted with permission or presumed to be in the public domain. Every effort has been made to ascertain and acknowledge their copyright status, but should there have been any unwitting oversight on our part, we would be happy to rectify the error in subsequent printings.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher.

Contents

The Idiot

Part One

A t about nine in the morning at the end of November in melting snow, the Warsaw train was steaming fast towards St Petersburg. It was so damp and foggy that the dawn light struggled to break through; nothing much was visible out of the windows ten paces either side of the track. Some passengers were homeward bound from abroad, but the third-class carriages were particularly crowded, in the main, with small-town, short-distance business travellers. All were, as is usual on such journeys, dog-tired and bleary-eyed; all were freezing cold with pallid faces to match the fog.

In one of the third-class compartments by the window two people had found themselves opposite each other from the small hours: both were young, travelling light; neither was too smartly dressed; both had rather distinctive features and finally both were ready to enter into conversation. Had either of them been aware of what it was that united them, theyd have wondered how it was that pure chance had brought them face to face in this third-class compartment of the Warsaw-St Petersburg train. One was short, about twenty-seven, with almost jet-black, wavy hair, and small, grey but fiery eyes. His nose was flat and wide, his cheekbones high; his thin lips were permanently curled into an arrogant, mocking, well-nigh malevolent smirk; his brow, however, was high and well formed, and more than made up for the ungainly, jutting lower part of his face. What was most remarkable about this face though was its deathly pallor, lending the young man an emaciated look even despite his rather powerful build; along with everything else, he exuded an ardour that bordered on anguish and did not accord at all well with his arrogant, almost truculent smile and the impudent smugness of his gaze. He was warmly dressed in a lined, black, wide-fitting sheepskin that kept him warm through the night, whereas his fellow traveller had endured the full rigour of a damp Russian November night totally unprepared. All the latter man wore was a fairly wide, coarse cloak with a huge hood, as is not infrequently worn by travellers wintering in distant parts, in Switzerland or even northern Italy, but something hardly designed for a journey such as that from Eydtkuhnen to St Petersburg. What was suitable and perfectly adequate for Italy was not nearly sufficient for Russia. The wearer of the cloak and hood was also about twenty-six or -seven, slightly taller than average, with a very fair complexion, a good head of hair, sunken cheeks and a sparse, barely noticeable, very pale goatee beard. His eyes were large, sky-blue and intense; his gaze was calm and brooding, suffused with that strange glow which some people immediately recognize as a sure symptom of the falling sickness. On the whole, however, his face was pleasant, fine and lean, but drained of colour, especially now that it was livid with cold. On his knees he cradled a pathetic little bundle, fashioned from a piece of worn, faded raw-silk fabric, evidently comprising all his worldly possessions. He wore a pair of thick-soled boots with cross-laced gaiters all very un-Russian. His dark-haired travelling companion in the lined sheepskin, partly from want of anything better to do, took all this in and, smiling that indiscreet smile which so often betrays mans delight in the discomfort of others, finally enquired, Feeling the cold, eh? And he jerked his shoulders.

Indeed, the other replied with extreme readiness, and, surprisingly, its thawing. I hate to think what its like when its freezing! I had no idea it could be so cold here in Russia. Comes as quite a shock.

Are you from abroad, or what?

Yes, from Switzerland.

Ha! Some people! The man made a whistling sound and burst out laughing.

A conversation ensued. The alacrity and candour with which the fair-haired young man in the Swiss cloak took to answering all the prying, indiscreet and at times obviously idle questions of his swarthy interlocutor was nothing short of remarkable. In the process, he openly admitted that he had not been back to Russia for a long time over four years and that hed been sent abroad for health reasons, with some strange nervous ailment like the falling sickness or St Vituss dance, with nervous contractions and spasms. Listening to him, the dark-haired man smirked a few times, particularly broadly when, in answer to his question, And did they cure you? the blond man replied, No, not really.

Ha! I thought as much, the dark man observed cuttingly, but you paid through the nose, and we here trust that lot.

Youre quite right! a badly dressed passenger, something like a lowly copy clerk, sitting nearby, butted in; he was a strongly built man of about forty, red-nosed, with a face marked by blotches. The truth is, they suck the lifeblood out of us Russians!

Oh, how wrong you are, gentlemen, as far as Im concerned anyway, the patient from Switzerland hastened to observe in a mild and conciliatory tone. Of course, Im in no position to argue because I dont know how it is with other people, but my doctor gave all he had to help me with my fare and besides he supported me for close on two years at his own expense.

There was no one else to pay, is that it? the swarthy man enquired.

Yes, Mr Pavlishchev, who funded me, died two years ago. I wrote to General Yepanchins spouse, a distant relative of mine, but received no reply. So I simply upped sticks and came over.

Over where?

You mean, where am I going to stay? I must say, I still dont know but

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Idiot»

Look at similar books to The Idiot. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Idiot and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.