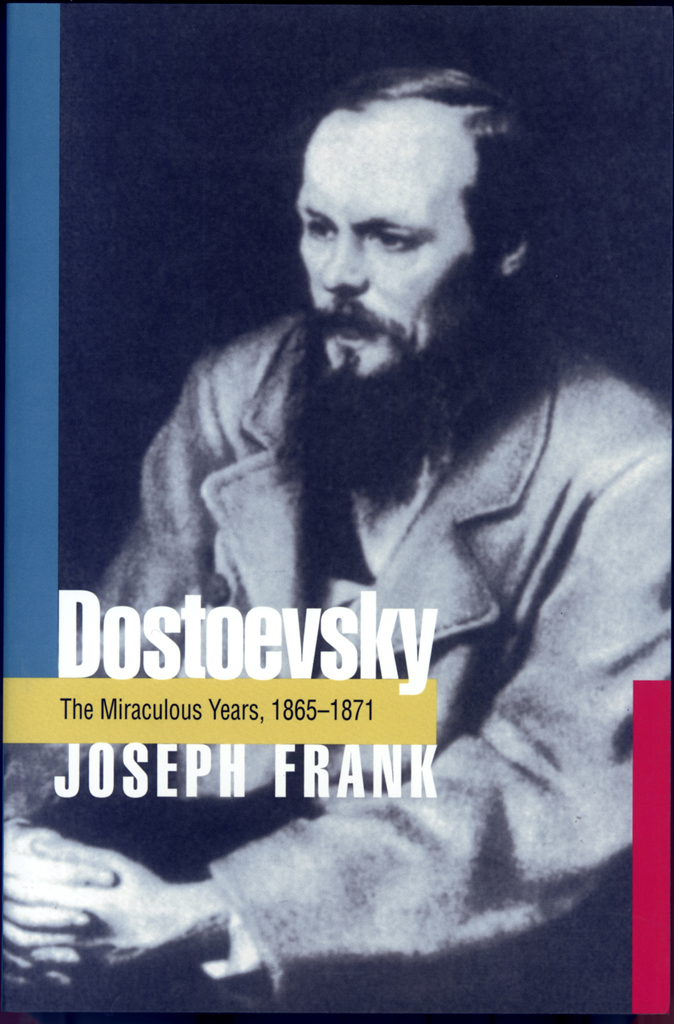

DOSTOEVSKY

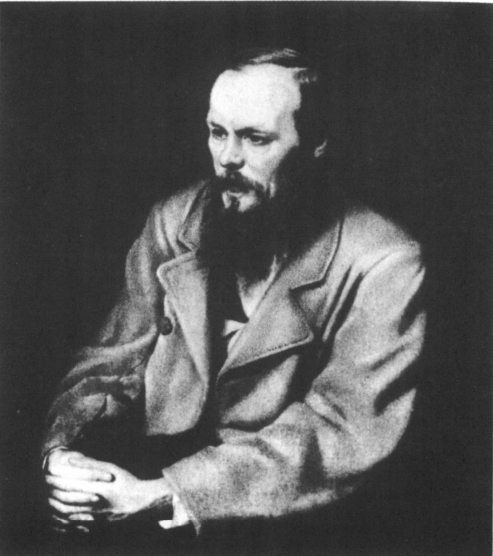

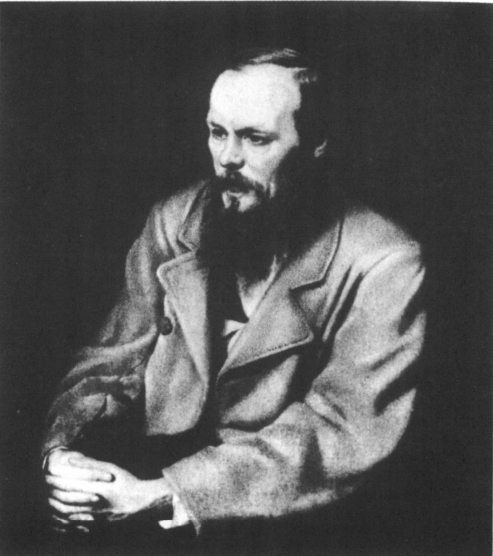

Dostoevsky in 1872, by V. G. Perov

DOSTOEVSKY

The Miraculous Years

1865-1871

JOSEPH FRANK

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY

PRESS

Copyright 1995 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, Chichester,

West Sussex

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Frank, Joseph (1918)

Dostoevsky: the miraculous years, 1865-1871 / Joseph Frank.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-691-04364-7

ISBN 0-691-01587-2 (pbk.)

1. Dostoyevsky, Fyodor, 18211881Biography.

2. Novelists, Russian19th centuryBiography.

3. RussiaIntellectual life1801-1917.

I. Title.

PG3328.F68 1995 891.933DC20 [B] 94-43403

9 10

ISBN-13: 978-0-691-01587-3 (pbk.)

ISBN-10: 0-691-01587-2 (pbk.)

eISBN 978-0-691-20937-1 (ebook)

R0

This book is dedicated to Richard

R. P. Blackmur (19041965)

A great critic, an irreplaceable friend,

who encouraged me to believe I

could someday write books

he would wish to read

CONTENTS

ix

xi

xv

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Unless otherwise noted, all illustrations are from Feodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky v Portretakh, illyustratsiyakh, dokumentakh, ed V. S. Nechaeva (Moscow, 1972).

Dostoevsky in 1872, by V. G. Perov. Bibliotheque Russe, Paris.

Courtesy of Collection Viollet

15. Claude Lorrain, Acis and Galatea. Dresden Museum.

Courtesy of Collection Viollet

PREFACE

The present work is the fourth volume in the series that I am writing on the life and works of Dostoevsky. The next volume, the last, will deal with the final ten years of his life. During the years covered here, Dostoevsky wrote three major novels and two novellas; these not only rank among his best works, but are among the greatest in Russian and in world literature as a whole. It is the production of such masterpieces that makes Dostoevskys life worth recounting at all, and my purpose, as in the previous volumes, is to keep them constantly in the foreground rather than treating them as accessory to the life per se. The aim of literary biography, as I conceive it, is to furnish readers with a context, drawn from the writers personal life, as well as from the social, cultural, literary, and philosophical background of his or her time, that will help toward a better understanding of the work. Without such application of its researches to the works themselves, literary biography, at least for me, loses much (if not all) of its presumed point. Hence I have included lengthy analyses of these celebrated novels and stories in the course of my narrative; and this has led to the present volume being rather bulkier than its predecessors, in which there were fewer works to discuss and ones that required less elucidation. But I found that I could not avoid placing this extra demand on the reader without infirming the very purpose of my endeavor.

Indeed, precisely because of the stature of the creations that it deals with, this fourth volume is a crucial one for my whole undertaking. I began with the idea, many years ago, that a close and exhaustive study of the Russian social-cultural context would yield more fruitful results for a better understanding of Dostoevsky than the usual approaches that had been taken, especially in Western criticism. These approaches had been mainly biographical in a narrowly personal sense, or psychological and psychoanalytical, or, influenced by Russian migr and Symbolist criticism, primarily religious and theological. Indigenous Russian criticism had paid more attention to Dostoevskys social-cultural environment, but reactions to his writings in his own time were naturally colored by the fierce political enmities of the period, which made any relatively objective appraisal of them impossible from this point of view. Later Russian criticism of this type, up to and through the Soviet period, only continued to reiterate the positions on the right and the left staked out in Dostoevskys own day. Or, as in the case of the Symbolists and the Formalists, who were determined to give Dostoevskys art its just due, the social-cultural context (except for its literary component) was swept aside as entirely irrelevant and, for the Symbolists, even demeaning to the universality of Dostoevskys thematic range and his inspired exploration of the eternal dilemmas of the human condition. Far be it from me to wish to diminish such an appreciation of Dostoevskys genius by one iota! But even more remarkable, I continue to think, is that he rose to such greatness from precisely those by-now musty arguments taking place among a handful of the intelligentsia in the long-ago Russia of the 1840s, 1860s, and 1870s. Without some knowledge of these bitter quarrels, destined to reverberate throughout the world up to our own time in Dostoevskys pages and those of others, and whose ultimate consequences are now being played out with the collapse of communism, we do not truly understand the sources of his inspiration or the passionsand apprehensionswhich, combined with his own life experiences and literary gifts, gave birth to his greatest work.

This was the point at which I started, and I well remember the words of my late and deeply lamented friend Irving Howe, whose own writings I admired and whose praise I greatly cherished, shortly after I had published my third volume and was chatting with him about the fourth. What he told me, in sum, was that my fourth, in which I should have to tackle three literary landmarks, would be the acid test of my belief that new and valuable light could be shed on them by an intensive study of their social-cultural genesis. These words rang in my ears as an inspiring challenge in all the years I have been writing this volume; and I looked forward to the pleasurenow, alas, foreclosedof presenting him with a copy to see if he thought the challenge had been met. Other readers will come to their own conclusions, and I can only hope that these will continue to be as favorable as they have been in the past.

DURING the period in which I have worked on this book, I have been fortunate in being surrounded by friends and colleagues whose knowledge and interests have provided support for my own efforts. Lazar Fleishman and Gregory Freidin of the Stanford Slavic Department have been an invaluable source of encouragement and insight, and I could rely on their native knowledge of Russian culture to buttress my own. Theodore and Rene Weiss of Princeton and Ian and Ruth Watt of Stanford were also friends to whom I could turn for literary stimulus and insight. Gary Saul Morson of Northwestern University and Caryl Emerson of Princeton University have been generous Slavic interlocutors as well, and offered welcome reassurance that I had not gone astray. Donald Fanger of Harvard, a major Dostoevskian himself, whose classic Dostoevsky and Romantic Realism has lost none of its value in thirty years, turned out to be a reader of the present book for Princeton University Press. His appreciative comments were a source of considerable pleasure and, as always, of great value. Another eminent fellow Dostoevskian, Jacques Catteau of the Sorbonne and the Institut dtudes Slaves, helped to make my Paris sojourns, with the aid of his wife, Jacqueline, personally pleasurable as well as scholarly profitable; and I have benefited a great deal from his own work and enlightening conversation in addition to the resources of the Institut dtudes Slaves, over which he presides.