DOSTOEVSKY

DOSTOEVSKY A Writer in His time

JOSEPH FRANK

edited by

Mary Petrusewicz

Copyright 2010 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock,

Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Second printing, and first paperback printing, 2012

Paperback ISBN 978-0-691-15599-9

The Library of Congress has cataloged the cloth edition of this book as follows

Frank, Joseph, 1918

Dostoevsky : a writer in his time / Joseph Frank.

p. cm.

Abridged ed. of authors work in 5 v.: Dostoevsky. c19762002.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-12819-1 (acid-free paper) 1. Dostoyevsky, Fyodor, 18211881. 2. Novelists, Russian19th centuryBiography. 3. RussiaIntellectual life18011917. I. Title.

PG3328.F75 2010

891.733dc22

[B] 2009001418

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Adobe Garamond

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

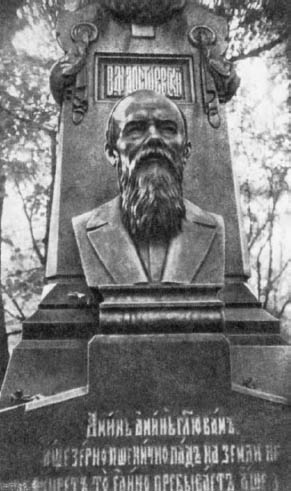

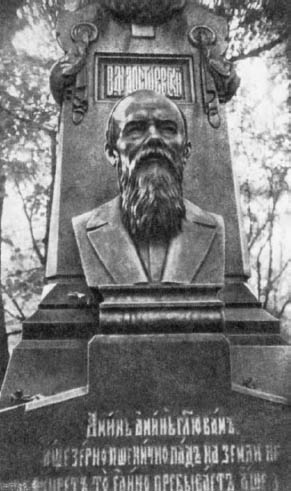

Frontispiece: The bust of Dostoevsky on his grave

Parched with the spirits thirst, I crossed

An endless desert sunk in gloom,

And a six-winged seraph came

Where the tracks met and I stood lost.

Fingers light as dream he laid

Upon my lids; I opened wide

My eagle eyes, and gazed around.

He laid his fingers on my ears

And they were filled with roaring sound:

I heard the music of the spheres,

The flight of angels through the skies,

The beasts that crept beneath the sea,

The heady uprush of the vine;

And, like a lover kissing me,

He rooted out this tongue of mine

Fluent in lies and vanity;

He tore my fainting lips apart

And, with his right hand steeped in blood,

He armed me with a serpents dart;

With his bright sword he split my breast;

My heart leapt to him with a bound;

A glowing livid coal he pressed

Into the hollow of the wound.

There in the desert I lay dead.

And God called out to me and said:

Rise, prophet, rise, and hear, and see,

And let my words be seen and heard

By all who turn aside from me.

And burn them with my fiery word.

A. S. Pushkin, The Prophet

trans. D. M. Thomas

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

Unless otherwise noted, all illustrations are from Feodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky v portretakh, illyustratsiyakh, dokumentakh, ed. V. S. Nechaeva (Moscow, 1972).

PREFACE

Dostoevsky: A Writer in His Time

Since the present volume is a condensation of the five that I have already published on the life and works of Dostoevsky, I should like to acquaint my new readers with the point of view from which they were written. My approach arose primarily from a troubling sense that important aspects of Dostoevskys work had been overlooked, or at least not accorded sufficient importance, in the considerable secondary literature devoted to his career. The major perspective of these studies derived from his personal history, and this had been so spectacular that it was almost irresistible for biographers to recount its peripeties at length. No other Russian writer of his stature could equal the range of his familiarity with both the depths and heights of Russian societya range that included four years spent as a convict living side by side with peasant criminals, and then, at the end of his life, invitations to dine with younger members of the family of Tsar Alexander II, who, it was believed, might benefit from his conversation. It is quite understandable that such a life, in all its fascinating particularities, should have furnished the background against which Dostoevskys works were initially viewed and interpreted.

The more I read Dostoevskys novels and stories, however, not to mention his journalism, both literary and political (his Diary of a Writer was the most widely circulated monthly publication ever published in Russia), the more it seemed to me that a conventional biographical point of view could not do justice to the complexities of his creations. To be sure, while Dostoevskys characters struggle with the psychological and sentimental problems that provide the substance of all novels, more important, his books are also inspired by the ideological doctrines of his time. Such doctrines, particularly in his major works, furnish the chief motivations for the often bizarre, eccentric, and occasionally murderous behavior of characters like Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment, or both Stavrogin and Kirillov in Demons. The personal entanglements of the figures in the novels, though depicted with often melodramatic intensity, cannot really be understood unless we grasp how their actions are intertwined with ideological motivations.

It thus seemed to me, when I set out to write my own work on Dostoevsky, that its perspective should be shifted, and that the purely personal biography should no longer dominate the explanatory context in which he was creating. Much less space is thus given in my books to the details of Dostoevskys private life and much more to the clash of various ideas prevailing during the period in which he lived. The most perceptive reader of my first four volumes, the much lamented and gifted novelist and critic David Foster Wallace, remarked that Ellmans James Joyce, pretty much the standard by which most literary bios are measured, doesnt go into anything like Franks detail on ideology or politics or social theory. This is not to say that I ignore Dostoevskys private life, but it remains linked to other aspects of his era that provide it with a much larger significance. Indeed, one way of defining Dostoevskys originality is to see in it this ability to integrate the personal with the major social-political and cultural issues of his day.

The above remarks about the shortcomings of the critical literature on Dostoevsky apply primarily to books in the various languages other than his own (mainly English, French, and German). It certainly cannot be said that the ideological and philosophical background of Dostoevskys creations has not been explored in Russian scholarship and criticism. Indeed, my own analysis of this background is greatly indebted to several generations of Russian scholars and critics such as Dimitry Merezkhovsky, Vyacheslav Ivanov, and Leonid Grossman, as well as to philosophers such as Lev Shestov and Nikolay Berdyaev. But as a result of the Bolshevik Revolution, it became difficult for Russian scholars, up until very recently, to build on these initiators and to continue to study Dostoevsky impartially and objectively. His greatest works, after all, had been efforts to undermine the ideological foundations out of which that revolution had sprung, and it was thus necessary to highlight his deficiencies rather than his achievements. As for migr scholars, with very few exceptions their works dwelt on the moral-philosophical implications of Dostoevskys ideas rather than on the texts themselves. While utilizing all this interpretative effort with gratitude, I have tried to rectify what seemed to me its limitations, whether caused by ideological restrictions or by nonliterary concerns.

Placing Dostoevskys writings in their social-political and ideological context, however, is only the first step toward an adequate comprehension of his works. For what is important about them is not that his characters engage in theoretical disputations. It is, rather, that their ideas become part of their personalities, to such an extent, indeed, that neither exists independently of the other. His unrivaled genius as an ideological novelist was this capacity to invent actions and situations in which ideas dominate behavior without the latter becoming allegorical. He possessed what I call an eschatological imagination, one that could envision putting ideas into action and then following them out to their ultimate consequences. At the same time, his characters respond to such consequences according to the ordinary moral and social standards prevalent in their milieu, and it is the fusion of these two levels that provides Dostoevskys novels with both their imaginative range and their realistic grounding in social life.

Next page