DOSTOEVSKY

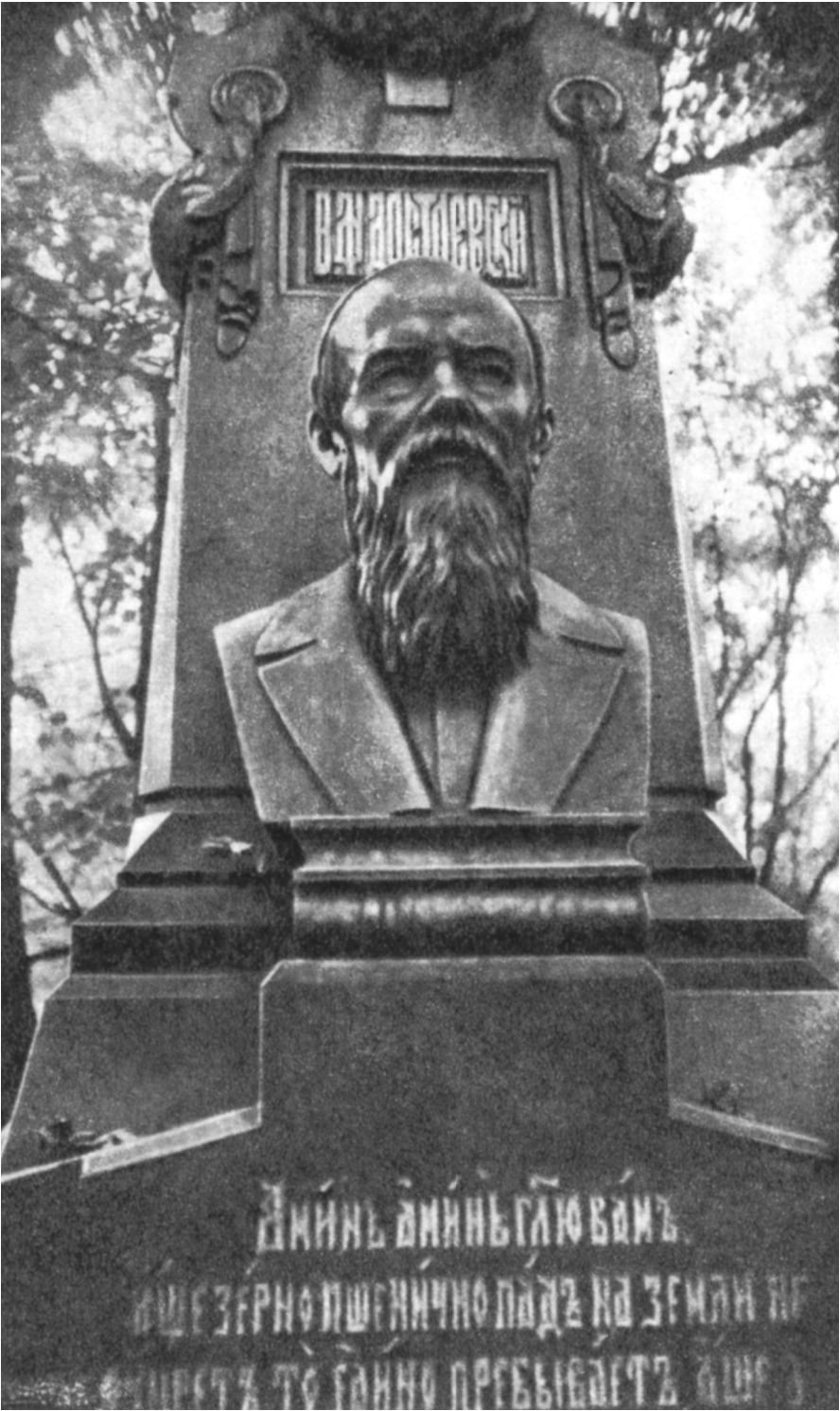

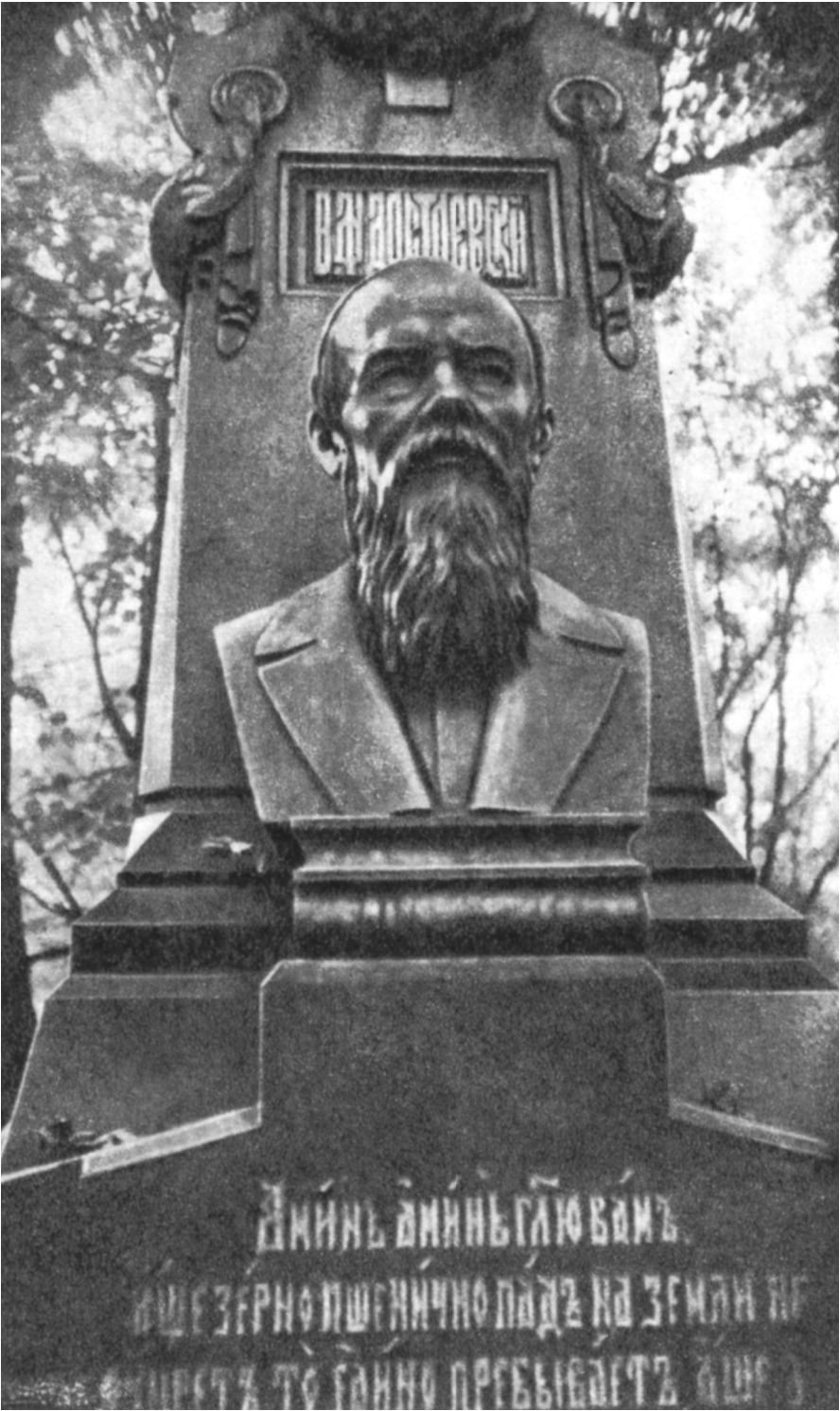

The bust of Dostoevsky on his grave

DOSTOEVSKY

The Mantle of the Prophet

18711881

JOSEPH FRANK

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON

AND OXFORD

Copyright 2002 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom:

Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

All Rights Reserved

Third printing, and first paperback printing, 2003

Paperback ISBN 0-691-11569-9

The Library of Congress has cataloged the cloth edition of this book as follows

Frank, Joseph (1918)

Dostoevsky : the mantle of the prophet, 18711881 / Joseph Frank. p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-691-08665-6 (cloth : alk. paper)

eISBN 978-0-691-20936-4 (ebook)

1. Dostoevsky, Fyodor, 18211881.

2. Novelists, Russian19th centuryBiography.

3. RussiaIntellectual life18011917.

I. Title: Mantle of the prophet, 18711881. II. Title.

PG3328 .F678 2002

891.733dc21

[B] 2001038749

R0

This final volume, like my first,

is dedicated to my wife,

Marguerite, my lifelong companion,

critic, and inspiration.

And to our

daughters Claudine and Isabelle,

and grandchildren Sophie and Henrik.

CONTENTS

ix

xi

xv

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Unless otherwise noted, all illustrations are from Feodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky v Portretakh, illyustratsiyakh, dokumentakh, ed. V. S. Nechaeva (Moscow, 1972).

The bust of Dostoevsky on his grave frontis

PREFACE

This is the fifth and final volume of my series of books on Dostoevsky. It marks the end of a long journey, and if someone, many years ago, had told me that I should someday embark on it, I would certainly have replied that nothing was more unlikely. Before undertaking the present work I had been primarily interested in contemporary literature, and had published a volume of essays (The Widening Gyre) that included Spatial Form in Modern Literature, still recognized as an important contribution to the aesthetics of the modern novel. I saw myself primarily as a literary critic, not as a biographer or cultural historian, though I had no objection to using whatever information was relevant to the better understanding of a work of art. My original project was thus to undertake a single, reasonably sized volume on Dostoevsky, devoted mainly to his novels. But by the time I came to write a first draft, the very nature of my approach made it almost inevitable that my initial intention would grow in size and scope. Indeed, it continued to do so even after I was well under way; and on completing my second volume, I realized that what had become a four-volume project would have to be extended to five.

My concern with Dostoevsky, as I explained in the preface to my first volume, had grown out of my interest in French Existentialism. For Sartre and Camus, a work such as Notes from Underground, and characters such as Raskolnikov (in Crime and Punishment) and Kirillov (in The Devils), had become essential landmarks to which they referred in defining their own points of view. (And of course it was not only for French Existentialists that Dostoevsky was important; his picture hung in Heideggers study throughout his lifetime.) But the more I read him, the more dissatisfied I became with the usual interpretations I encountered. Either he was viewed largely in purely personal, psychological terms, or he was discussed in relation to the general philosophical and theological issues raised in his novels; and these were frequently, as in the case of Existentialism, linked to one or another contemporary philosophical movement, beginning with the Nietzschean vogue of the late nineteenth century.

It is impossible to read Dostoevsky, however, without becoming aware that his major characters are deeply involved in the social-political ideologies and problems of their time; but his own so-called political ideas seemed so eccentric that hardly anyone took them seriously. Indeed, it was felt necessary to get them out of the way if one were to do him justice as a novelist. I still recall an article by Philip Rahv on The Devils many years ago, in which, while praising Dostoevskys prophetic insight into the dangers of Russian radicalism, the critic carefully explained that he had known nothing about Socialism. But if he could read the future of Socialism in Russia with such clairvoyance, how could he have been so ignorant of what its doctrines really represented?

Questions such as these arose for me regarding other works as well, and I found highly unsatisfactory the general notion that, since Dostoevskys involvement with the ideologies of his time seemed so unsympathetic, it was best either to forget about them or to expatiate on the vast difference between literary creativity and social-political sobriety. Moreover, the more I learned about the actual social-cultural context from which his writings had emerged, the more I began to feel that the usual opinion should be entirely reversed, and that it was necessary to study their ideological background very carefully. To be sure, this analysis had been undertaken very conscientiously in contemporary Russian criticism and scholarship of the last half-century, and I have drawn freely and gratefully on its results. But, as I also became aware, these scholars were forced to adopt a view of Russian cultural history that placed severe constraints on how they could interpret the role played by Dostoevsky in their own past. There thus seemed to be room for a study unhampered by such limitations, one that probed his point of departure with as much objectivity and impartiality as possible.

Of course, Dostoevskys genius raised the problems he was dramatizing to moral-philosophical heights involving the most crucial questions of Judeo-Christian thought and experience. My aim was certainly not to remove them from this empyrean realm; but these questions had been posed for him in the Russian terms of his own time and place, and if we are to follow the trajectory by which they were elevated to a level rivaling that of great poetic tragedy, it seemed to me necessary to grasp their point of origin as accurately as could be done.

My own attempt along these lines began with Notes from Underground. It was in grappling with this text that I began to understand the complexity of the relations in his writings between psychology and ideology, and how important it was for a proper comprehension of the first to identify its roots in the social-cultural context of the second. Once launched, I continued to investigate other works from the same point of view, and finally to study his creative career as a whole. But I thought it essential, as a literary critic, not only to explore this context but also to show how it could be applied to offer fresher views of Dostoevskys artistic aims and accomplishments.

Each of my previous books has thus been dominated by the ideology of the period in which Dostoevsky was creating, and in this final one I focus on the relatively unexplored relation of his novels of the 1870s to the doctrines of Russian Populism. Since I was, however, writing for American readers who had only the haziest knowledge (if any at all) of Russian cultural history, this meant filling in the background at some length. It was this necessity that ultimately compelled me, as the pages piled up, to abandon my one-volume idea and to settle down for the long haul.