Pagebreaks of the print version

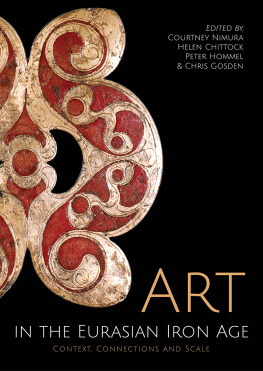

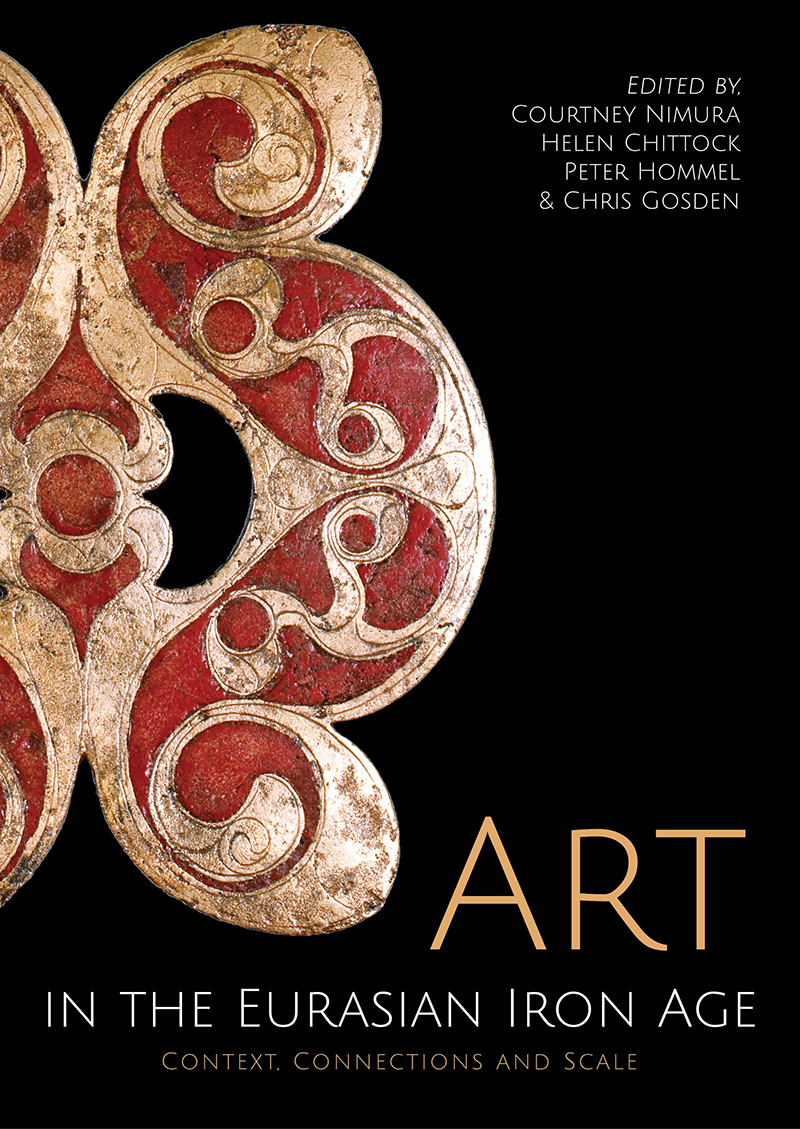

Art in the Eurasian Iron Age

Art in the Eurasian Iron Age

Context, connections and scale

edited by

Courtney Nimura, Helen Chittock, Peter Hommel and Chris Gosden

Published in the United Kingdom in 2020 by

OXBOW BOOKS

The Old Music Hall, 106108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JE

and in the United States by

OXBOW BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083

Oxbow Books and the individual contributors 2020

Hardback Edition: ISBN 978-1-78925-394-8

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78925-395-5 (ePub)

Kindle Edition: ISBN 978-1-78925-396-2 (mobi)

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019951276

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

For a complete list of Oxbow titles, please contact:

UNITED KINGDOM | UNITED STATES OF AMERICA |

Oxbow Books | Oxbow Books |

Telephone (01865) 241249 | Telephone (610) 853-9131, Fax (610) 853-9146 |

Email: | Email: |

www.oxbowbooks.com | www.casemateacademic.com/oxbow |

Oxbow Books is part of the Casemate Group

Front cover : A Late Iron Age (100 BCAD 43) harness plate from Santon, Suffolk. Reproduced by permission of University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology (1897.225A).

List of figures and tables

Fig. 1.1 Some of the material from Waldalgesheim, including neck and arm rings and a detail of the decoration below the bucket handle (after Lindenschmit 1881, taf. 1. Reproduced from Joachim 1995, 12, abb. 4).

Fig. 1.2 Detail of the decoration on the neck ring ( LVR-LandesMuseum Bonn, Sigrun Wischhusen. Reproduced from Joachim 1995, 61, abb. 37).

Fig. 2.1 The distribution of all object findspots in the ECAIC database.

Fig. 2.2 Quantities of objects from the 47 countries represented in the ECAIC database.

Fig. 2.3 The overall frequencies of different object categories in the ECAIC database.

Fig. 2.4 The distribution of torc findspots from the ECAIC database.

Fig. 2.5 The distribution of brooch findspots from the ECAIC database.

Fig. 2.6 The distribution of objects from funerary sites in the ECAIC database.

Fig. 2.7 Frequencies of different objects from settlement sites in the ECAIC database.

Table 2.1 ECAIC database fields.

Fig. 3.1 Map showing locations of sites mentioned in the text. The burial mounds of Grafenbhl, Hirschlanden, Hochdorf, Kleinaspergle and Rmerhgel are all associated with the hilltop site of Hohenasperg (base map: Ktrinko, Eckert4, Wikimedia).

Fig. 3.2 Map of Eurasia showing with drawn ovals some of the interaction spheres evident in the distributions of the archaeological evidence. This map is highly simplified and could be greatly expanded by adding additional data. Many other categories of material could be shown, such as the distribution of Attic pottery and that of objects produced in the Greco-Scythian style. This map is intended not as a final document, but as a suggestion for ways of thinking about the interactions throughout Eurasia. Important is the overlapping of the spheres, meant to suggest the complex pattern of intersecting systems along which people, objects and ideas circulated. For literature on each label, see pp. 4546 (base map: Ktrinko, Eckert4, Wikimedia).

Fig. 4.1 Map of Eurasia with sites and locations mentioned in this chapter: Torrs Loch (1), Vix (2), Garchinovo (3), Aksyutintsy (4), Tolstaya Mogila (5), Obrucheski (6), Berel (7), Pazyryk (8), Jiaohegou (9), Majiayuan (10), Xichagou (11).

Fig. 4.2 Distribution and concentration of the motif known as the curled predator across Eurasia (data from Vasilev 2000). Inset: early example of the motif on a bronze harness fitting from Arzhan I, Republic of Tuva (Photo: P. Hommel).

Fig. 4.3 Distribution, number and typological variety of composite images as a subset of the corpus of animal art in Scythian burials across the northern Pontic steppe (data from Kantorovich 2015a; mapped using a 0.5 grid). The outer line indicates the total number of artistic representations within one grid square, and the inner dot represents the number of composite animals. The colour (from light to dark) represents the number of unique typological variants of composite images as classified by Kantorovich 2015a. Accepted areas of Greek colonial settlements are shown as hatched areas.

Fig. 4.4 Bronze raptor head with a rams horns. Kurgan 2 Semibratev, Taman Peninsula, 5th century BC (after Artamonov 1966, pl. 115).

Fig. 4.5 Plaque of a deer with stylised antlers where the tines end in raptor heads. An inverted raptor head is also visible behind the shoulder. Mound 2, Aksyutintsy, Ukraine, 7th6th century BC.

Fig. 4.6 Silver Thracian beaker (4th century BC) showing a design of a deer with eight legs and antlers that encircle the vessels upper register. It appears to stand on land with waves present slightly below its hooves (courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, accession number: 47.100.88).

Fig. 4.7 A deer stone at Jargalantyn Am, Arkhangai aimag, Mongolia ( c. 930785 BC). Multiple deer encircle the stele, which is separated into three parts by a belt from which tools hang and a necklace-like ring at the top (Image and drawing: P. Hommel).

Fig. 4.8 Okunev stele near Lake Beloye, Khakassia, c. 27001800 BC (Drawing: P. Hommel).

Fig. 4.9 Carved depiction of a fantastic creature with bovid horns and a tongue that looks like both a snakes tongue and lightning. Detail from panel at Kurgan 3, Byrkanov, Khakassia, c. 27001800 BC (Drawing: P. Hommel after Kurochkin 1995).

Fig. 5.1 An anthropomorphic bronze sword hilt from Saint-Andr-de-Lidon, Charente-Maritime, France (Muses de la ville de Saintes) (Illustration: H. Chittock).

Fig. 5.2 The distribution of anthropomorphic imagery in the ECAIC database.

Fig. 5.3 The distribution of anthropomorphic imagery on items of personal ornament in the ECAIC database.

Fig. 5.4 The Glauberg Statue ( c. 500 BC). Height: 186 cm (Keltenwelt am Glauberg) (Illustration: H. Chittock).

Fig. 6.1 Paul Kles ambling lines (A) and connecting lines (B).

Fig. 6.2 Openwork disk. Bronze. Somme-Bionne, LHomme Mort (Marne). London, British Museum ( Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved).

Fig. 6.3 Painted motif exemplifying anamorphosis. Ceramic. Thuisy (Marne). Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Muse dArchologie nationale, Inv. MAN 27676 (Photo: MAN).

Fig. 6.4 Linchpin with zoomorphic motif. Bronze and iron. Roissy, La Fosse Cotheret (Val-dOise), wagon grave 1002 Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Muse dArchologie nationale, Inv. MAN 89206.023 (Photo: MAN).

Fig. 6.5 Openwork plate with dragon motif. Bronze. Cuperly (Marne). Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Muse dArchologie nationale, Inv. MAN 27719 (Photo: MAN).

Fig. 6.6 Yoke ring with human mask motif. Bronze. Paris (Seine). Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Muse dArchologie nationale, Inv. MAN 51399 (Photo: MAN).