City of Refuge

SEPARATISTS AND UTOPIAN TOWN PLANNING

MICHAEL J. LEWIS

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

To Heinz and Susanne Baldermann,

who kindly opened up for me their own City of Refuge in the Haasemannstrae

Copyright 2016 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom:

Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Jacket illustration: Frederick Rapp, drawing of the central pavilion of the Economy garden; Manuscript Group 185, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission: Old Economy Village Archives, OE-83-4-5.

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-17181-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lewis, Michael J., 1957 author.

Title: City of Refuge : separatists and utopian town planning / Michael J. Lewis.

Description: Princeton : Princeton University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015049233 | ISBN 9780691171814 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Collective settlements. | City planningReligious aspects. | City planningSocial aspects. | Utopias.

Classification: LCC HX630 .L49 2016 | DDC 307.77dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015049233

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Designed and typeset by Jeff Wincapaw

This book has been composed in Whitman

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in China

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

City of Refuge

The Idea of the City of Refuge

And among the cities which ye shall give unto the Levites there shall be six cities for refuge.

(NUMBERS 35:6, KJV)

Almost every society has an image of a perfect world, however vague its outlines and imprecise its coordinates. It can loom dimly in the past as a remote golden agea lost Arcadiaor as a prophecy of things to come, in this world or the next. It can be a purely philosophical exercise like Platos Republic, or a political promise, the alluring dream of a socialist workers paradise. It scarcely matters that this perfect world is unattainable. The more distant and remote the vision, the better to cudgel the present and to expose its faults and failings.

Five hundred years ago, Thomas More published a book that made it possible for the first time to speak collectively of all these notions of perfection, whether mythical, philosophical, theological, or merely administrative. His title coined that brilliant new word, the sonorous and immensely suggestive Utopia, which subsumed all these different conceptions of human perfectionGreek and Roman, Jewish and Christianinto a single irresistible vision. This vision has become a potent force in Western culture, where radical campaigns for social reform soon came to arouse the kind of rapturous millennial hopes once restricted to heavenly paradise. A good portion of the history of the past five centuries is the story of utopian revolutions and their consequences.

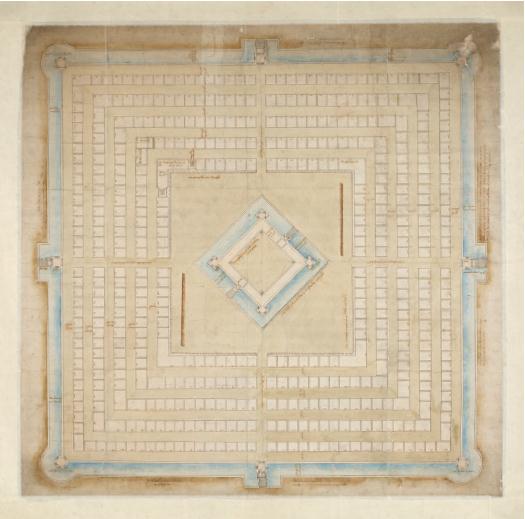

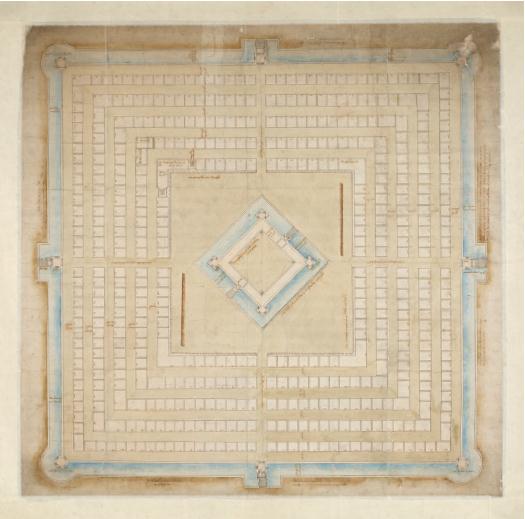

FIG. 1 The city of refuge is the dissenters Utopia, a foursquare sanctuary for the refugees displaced by the religious wars of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Freudenstadt in Swabia was designed by Heinrich Schickhardt in 1599, for whom rectilinear order was so important that he bent the church on the main square rather than violate his regular plan.

This is the main utopian tradition, which aspires to perfect the world and liberate it from strife, want, and woe. But alongside it runs a second strand of thought that recognizes that the corrupt world, however much we tamper and tinker, cannot be made perfect, and that squalor and discord are the natural state of baffled human existence. This alternative tradition was carried forward by sects that had received their fill of official harassment and unofficial violence, including German Rappites, French Huguenots, and American Shakers. Seeing no hope for reforming a wicked world, they chose instead to withdraw from it. They made their way to distant sanctuaries, where they withdrew from society to establish detached and independent communities ). These separatist enclaves, dissimilar in theology but similar in their urban practice, form a distinct and unbroken intellectual tradition, one that runs parallel to the main channel of utopian thought. It is the living continuity of that tradition that is the theme of this book.

The phrase city of refuge derives from the Bible, for it was only logical that Christian societies suffering persecution and seeking sanctuary look there to find solace and guidance. It was natural that they should identify themselves with the ancient Israelites on their exodus through the wilderness, and even that their towns should imitate the layout of the Israelite encampments during those wanderings. But the Bible offers another image for persecuted refugees, a strangely hopeful one, and that is the city of refuge described in the book of Numbers. There we read how Moses, following Gods instructions, allocated the Promised Land among the twelve tribes of Israel. Forty-eight cities were to be given to the Levite tribe; of these six were awarded the special designation of cities of refuge ( in Hebrew, Orei Miklat). Someone guilty of manslaughter could flee to one of these cities without fear of being avenged by the victims family:

And the Lord spoke to Moses, saying, Speak to the people of Israel and say to them, When you cross the Jordan into the land of Canaan, then you shall select cities to be cities of refuge for you, that the manslayer who kills any person without intent may flee there. The cities shall be for you a refuge from the avenger, that the manslayer may not die until he stands before the congregation for judgment. And the cities that you give shall be your six cities of refuge. You shall give three cities beyond the Jordan, and three cities in the land of Canaan, to be cities of refuge. These six cities shall be for refuge for the people of Israel, and for the stranger and for the sojourner among them, that anyone who kills any person without intent may flee there.

(NUM. 35:9 15)

Only much later in the Bible (Josh. 20:78) are the names of those six cities revealed: Kadesh, Shechem, and Hebron on the east side of the Jordan, and Bezer, Ramoth, and Golan on the west. A glance at a map shows that they are spaced across ancient Israel with remarkable evenness, according not to population but geography, thereby reducing as much as possible the longest potential flight of a fugitive. A refuge needs to be close at hand.

The Greeks refused to drag fugitives out forcibly from their temples (although, as the Spartan general Pausanias found, they were quite willing to starve them out). Christianity continued this ancient practice, which was formalized in 511 at the First Council of Orlans, which granted the right of asylum to anyone who could make his way to a church or the house of a bishop. Hence, the English word sanctuary signifies both a place of refuge and the holiest part of a church building.

But the Jewish tradition was unusual in declaring not merely a temple or altar but an entire city as a sanctuary. And so the idea slumbered through the centuries, right until the dawning of the Protestant Reformation.

Next page