Contents

Page List

Guide

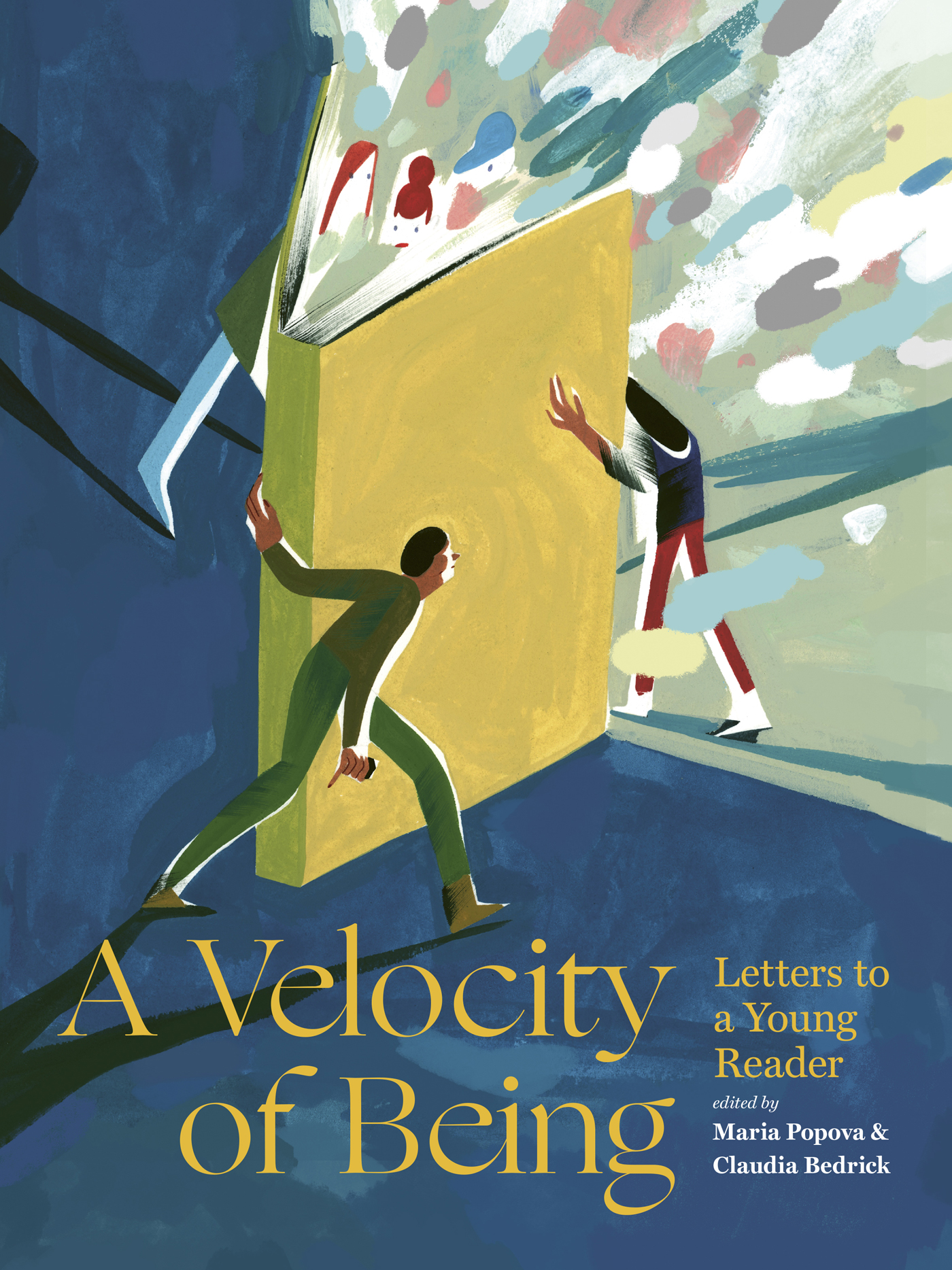

A Velocity of Being

For Stella, Gibson, and Ash.

Maria Popova

For Elias and Theo, my sisters,

my parents, my friend and mentor Arien Mack,

and the Donnell and Widener libraries,

for sharing the world as it is and as it has been dreamed,

interpreted, imagined, and might be with me.

Claudia Zoe Bedrick

A Velocity of Being

Letters to a Young Reader

edited by

Maria Popova and Claudia Zoe Bedrick

ENCHANTED LION BOOKS

NEW YORK

Introduction

By Maria Popova

W hen asked in a famous questionnaire devised by the great French writer Marcel Proust about his idea of perfect happiness, David Bowie answered simply: Reading.

Growing up in communist Bulgaria, the daughter of an engineer father and a librarian mother who defected to computer software, I dont recall being much of an early readera literary debt I seem to have spent the rest of my life repaying. But some of my happiest memories are of being read tomost deliciously by my grandmother. I remember her reading Alices Adventures in Wonderland to me, long before I was able to appreciate the allegorical genius of this story written by a brilliant logician.

My grandmother, an engineer herself, had and still has an enormous library of classical literature, twentieth-century novels, andmy favorite as a childvarious encyclopedias and atlases. But it wasnt until I was older, when she told me about her father, that I came to understand the role of books in her lifenot as mere intellectual decoration, but as a vital life force, as meat and medicine and flame and flight and flower, in the words of the poet Gwendolyn Brooks.

My great-grandfather had been an astronomer and a mathematician who, in the thick of Bulgarias communist dictatorship, taught himself English by hacking into the suppressed frequency of the BBC World Service and reading smuggled copies of The Catcher in the Rye, Little Women, The Grapes of Wrath, and a whole lot of Dickens and Hemingway. This middle-aged rebel would underline words in red ink, then write their Bulgarian translations or English synonyms in the margins. By the time he was fifty, he had become fluent. When his nine grandchildren were entrusted to his care, he set about passing on his insurgent legacy by teaching them English. When the kids grew hungry during their afternoon walks in the park, he wouldnt hand out the sandwiches until they were able to ask in proper Queens English.

I never met my great-grandfatherhe died days before I was bornbut I came to love him through my grandmothers recollections. Around the time when she first began regaling me with them, unbeknownst to me, a young American woman named Claudiaa philosophy graduate student at the New School for Social Research in New Yorkbegan visiting libraries and universities across Eastern and Central Europe on various foundation grants as a representative of a Graduate Faculty program designed to support libraries and scholars throughout that region after nearly half a century of intellectual isolation. She visited libraries to talk about the social sciences and humanities, and to learn how local collections worked. She met with librariansthe keepers of the keyswho would show her beautiful illustrated books, illuminated manuscripts, incunabula, and rare journal archives. And she began to seek out picture books from local bookstores, perhaps even some that my grandmother was reading to me at that very time.

Years later, that young woman would become an independent publisher of beautiful, unusual, conceptual childrens booksthe kind I would go on to celebrate in my own adult life, having transplanted myself from Bulgaria to Brooklyn, in no small part thanks to a life of reading.

And so it was that a package arrived in my Brooklyn mailbox one day, containing three exquisite wordless picture books by a French artistnot childrens books so much as visual works of philosophy, telling thoughtful and sensitive stories of love, loss, loneliness, and redemption. Enchanted, I looked for the sender and was astonished to find an address in the building next door. Enchanted Lion Books, it said. How perfect, I thought.

The senders name was Claudia Zoe Bedrick, the publisher. Apparently, we had been working at adjacent studios on the same Brooklyn block. And so Claudia and I finally met, having orbited each other unwittingly for decades, around the shared sun of story and image.

The dawn of our fast friendship was also a peculiar point in culture. Those were the early days of ebooks and the golden age of social media, when the very notion of readingof intellectual, emotional, and spiritual surrender to a cohesive thread of thought composed by another human being, through which your own interior world can undergo a symphonic transformationwas becoming tattered by the fragment fetishism of the Web. Even those of us who partook in the medium openheartedly and optimistically were beginning to feel the chill of its looming shadow.

Once again, I found myself torn between two worldsnot ideologies as starkly recognizable as the Bulgarian communism of my childhood and the American capitalism of my adulthood, but distinct paradigms nonetheless. I reconciled thema subjective, personal reconciliation, to be sureby spending my days reading books, mostly tomes of timeless splendor written long ago by people dead and often forgotten, then writing about them on the Internet, which I came to use as one giant margin for annotating my readings, my thoughts, and my search for meaning. Although I have always been agnostic about the medium of readingI refuse to believe that reading Aristotle on a tablet or listening to Susan Sontag in an audiobook is necessarily inferior to reading from a printed bookI was beginning to worry, as was Claudia, about what reading itself, as a relationship to ones own mind and not a relationship to the matter of silicon or pulped wood, might look like for the generations to come.

I took solace in a beautiful 1930 essay by Hermann Hesse titled The Magic of the Book, in which the Nobel laureate argued that no matter how much our technology may evolve, reading will remain an elemental human hunger. Decades before the Internet as we know it existed, Hesse wrote: We need not fear a future elimination of the book. On the contrary, the more that certain needs for entertainment and education are satisfied through other inventions, the more the book will win back in dignity and authority.

Animated by a shared ardor for that dignity and authority of the written word, Claudia and I decided to do something about itwhich is, of course, always the only acceptable form of complaintnot by fear-mongering or by waving the moralizing should-wand, but by demonstrating as plainly yet passionately as possible that a life of reading is a richer, nobler, larger, more shimmering life. And what better way of doing that than by inviting people cherished for having such livescelebrated artists, writers, scientists, and cultural heroes of various stripesto share their stories and sentiments about how reading shaped them? After all, we read what we are as much as we are what we read.

So began an eight-year adventure of reaching out to some of the people we most admired, inviting each to write a short letter to the young readers of today and tomorrow about how reading sculpted their character and their destiny. We then paired each letter with an illustrator, artist, or graphic designer to bring its message to life visually.