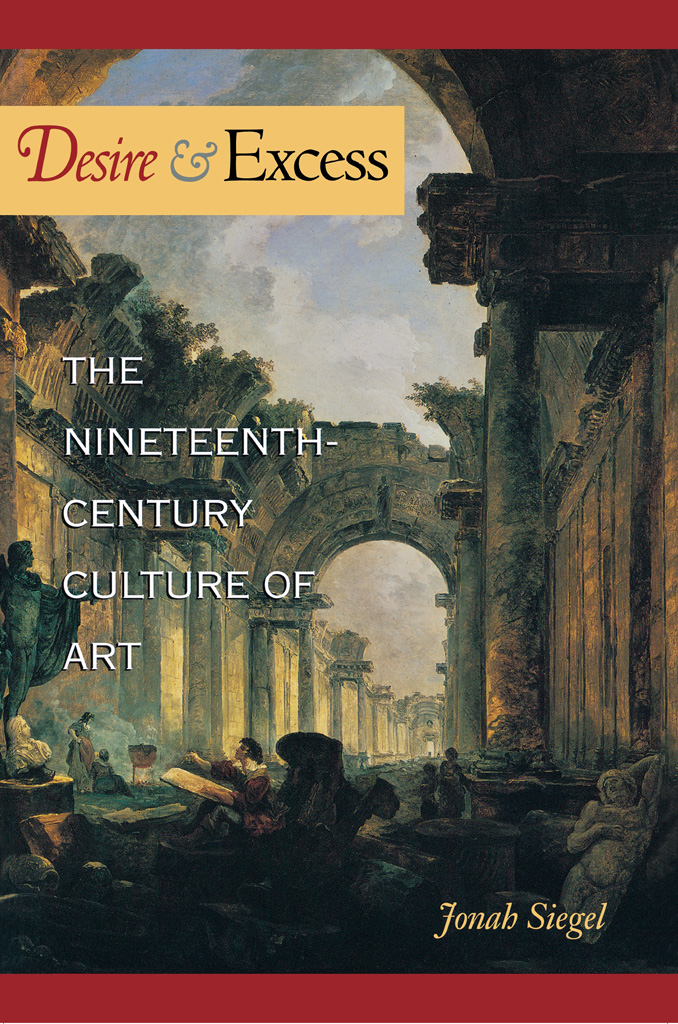

DESIRE AND EXCESS

DESIRE AND EXCESS

THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY

CULTURE OF ART

JONAH SIEGEL

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

To Nancy Yousef

Copyright 2000 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock,

Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Siegel, Jonah, 1963

Desire and excess : the nineteenth-century culture of art / Jonah Siegel.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 0-691-04913-0 (cl : alk. paper) ISBN 0-691-04914-9 (pb : alk. paper)

eISBN 978-1-400-84982-6

1. Arts, Modern19th centuryHistoriography. 2. Art and literatureHistory19th

century. 3. ArtistsHistory19th century. I. Title.

NX454 .S54 2000

709'.03'4dc21 00-020897

www.pup.princeton.edu

R0

LIST OF FIGURES

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

T HIS BOOK is about the difficult relationships between past work and modern workers on the one hand and between excess and admiration on the other. Both themes come into play as I stop to thank the many who have contributed to the production of Desire and Excess. To begin with, I must express my gratitude to the myriad strangers whose names run through the references in this book. A project of this scope relies on the work of others to a greater degree than may be comfortable, but the amount of careful, detailed, measured, and passionate work I have found on almost every theme and topic this book touches has been a constant source of wonder to me. Coming from literary studies into a project involving not only the visual arts but the history of the arts and their institutions has only been possible because art historians have produced books and articles hospitable and even inspiring to a stranger from another discipline.

As I turn to institutions and people who have had a more direct impact on me personally, I am distressed by the near certainty of losing admiration in numbers; given the many particular and individual debts I have acquired in the production of this book over nearly a decade, it troubles me to dilute the real force of my gratitude in the sheer quantity of those I cite. To begin with institutions:

The research and production of this book were aided by grants from Rutgers University, as well as from the Robinson and Rollins funds of the Harvard English Department, and two Clark grants from Harvard University. The final stages of revision took place during a leave year at the National Humanities Center made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. I was fortunate to be able to revisit this material in such a congenial environment, while benefiting from the conversation and many kindnesses of a notable collection of gifted scholars.

I am grateful to Eliza Robertson and Jean Houston at the Center for their cheerful aid in tracking down obscure sources. I must also thank Karen Carroll and Brian R. MacDonald for painstaking work in editing the text, and Virginia Middlemiss in New York for creative and dedicated labor as a picture researcher. The earliest and most entertaining aid I received in this was from my friend and quondam research assistant, Scott Karambis. More recently, I have become greatly indebted to Ellen Foos and Mary Murrell at Princeton University Press for the imagination and patience they have brought to this project.

This book has been extremely lucky in the readers it has encountered thus far, and it is with pleasure and gratitude that I acknowledge them. In the long course of writing, I benefited from the counsel of many readers of individual chapters; my thanks to Michel Chaouli, Jed Esty, Monica Feinberg, Nick Jenkins, Karl Kroeber, Michael Matin, Jesse Matz, Franco Moretti, Sophia Padnos, John Rosenberg, Elaine Scarry, Michael Seidel, Joe Viscomi, and Sherri Woolf. The close attention of friends and strangers to material often quite distant from their own interests has been nothing short of inspiring. Readers of the entire manuscript in its various stages have included James Eli Adams, Isobel Armstrong, Ian Duncan, Carol Forney, Rochelle Gurstein, Andreas Huyssen, Bob Kiely, Martin Meisel, Robert Rosenblum, Helen Vendler, and Lynn Wardley. While the creativity and generosity of these readers have aided this project immeasurably, my embarrassment at the need to commemorate so much individual care and thoughtful exchange in a set of undifferentiated lists is only compounded when I consider how far I still am from bringing this book to the level that others envisioned for itor challenged it to reach.

Desire and Excess began as graduate work at Columbia University supervised by Steven Marcus. I am happy to have the opportunity to acknowledge my long-standing debt to his forbearance, rigor, and intellectual commitment. I am grateful, also for the astute eclecticism and playful imagination of David Damrosch and the wide ranging erudition of Richard Brilliant, the two other early supporters of the project. I can only wonder at the cheerful engagement of these individuals in an endeavor that often must have seemed at risk of exploding at the seams. Stephen Donadio will recognize the roots of this volume in work we did together long ago.

Desire and Excess gained much from the encouragement and collegiality I was fortunate to experience while at the Harvard English Department. I must acknowledge in particular the two thoughtful and responsive chairs under whom I served, Leo Damrosch and Larry Buell, as well as Isobel Armstrong, Elaine Scarry, and Helen Vendler, whose guidance and support have been unexpected, multifaceted, and invaluable. For solidarity and what was, all things considered, an unusually pleasant introduction to the life of an assistant professor I would like to thank those who preceded me and set the tone, Phil Harper, Jeff Masten, Meredith McGill, Wendy Motooka, and Lynn Wardley in particular. Outside of the department, I am extremely grateful to Sue Lonoff for inviting me to chair with her the Victorian Seminar of the Center for Literary and Cultural Studies at Harvard.

Moving from lists of names to only more inadequate collective nouns, I would like to register my gratitude to the remarkable family and friends who have been, whether near or far, a consistent source of emotional and intellectual support during the long and eventful period in which Desire and Excess was conceived and written. This book is dedicated to Nancy Yousef, who is both family and friend. I write these acknowledgments on the anniversary of our marriage, counting it my special fortune to have had her as the first and last reader of this manuscript. Her sympathetic imagination and uncompromising intellect have done so much in aid of this endeavor that I can only wonder at the thought that it is not the most she has done for me.

PREFACE

THE APPARENT PERMANENCE OF THE MUSEUM

AS AGAINST ITS ACTUAL PERMANENCE:

THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY CULTURE OF ART

I F THE WALLS of the museums were to vanish, and with them their labels, what would happen to the works of art that the walls contain, the labels describe? Would these objects of aesthetic contemplation be liberated to a freedom they have lost, or would they become so much meaningless lumber? To pose this question in such exaggerated terms is one way to begin to consider the productive work of institutions in culture, the manner in which institutions not only contain cultural desires but shape them as well. The uncertain and contentious nature of art in contemporary culture has been made clear by any number of recent controversies. This book argues that such uncertainty, far from being a late development, has sources traceable to the very foundations of the modern system of art as it was established in an earlier era. It identifies in particular the embattled accounts of the artist that have typically been understood as resulting from the challenges of self-consciously new movementsof modernism or even postmodernismas having sources deep in the nineteenth-century culture of art that gave rise to the modern artist in the first place.