Charlemagne and Louis the Pious

Charlemagne and Louis the Pious

The Lives by Einhard, Notker, Ermoldus, Thegan, and the Astronomer

Translated with

Introductions and Annotations

by Thomas F. X. Noble

The Pennsylvania State University Press

University Park, Pennsylvania

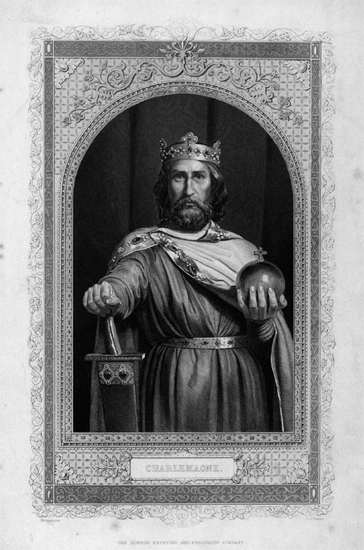

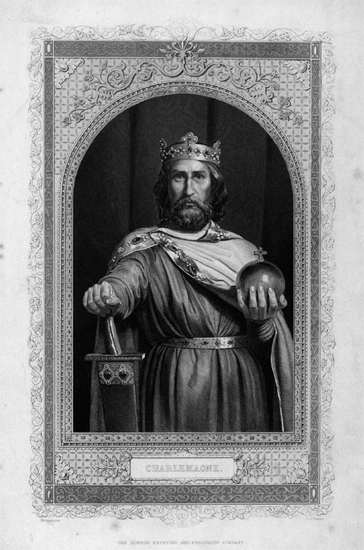

Frontispiece: Charlemagne, Print Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Charlemagne and Louis the Pious : lives by Einhard, Notker, Ermoldus, Thegan, and the Astronomer / translated with introductions and annotations by Thomas F.X. Noble.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Summary: Translations of ninth-century lives of the emperors Charlemagne (by Einhard and Notker) and his son Louis the Pious (by Ermoldus, Thegan, and the Astronomer).

Presented chronologically and contextually, with commentaryProvided by publisher.

ISBN 978-0-271-03573-4 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Charlemagne, Emperor, 742814.

2. Louis I, Emperor, 778840.

3. Holy Roman EmpireKings and rulersBiography.

4. FranceKings and rulersBiography.

5. Holy Roman EmpireHistoryTo 1517Sources.

6. FranceHistoryTo 987Sources.

I. Noble, Thomas F. X. DC73.6.C44 2009

944'.01420922dc22 2009012104

Copyright 2009

The Pennsylvania State University

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Published by The Pennsylvania State University Press,

University Park, PA 16802-1003

The Pennsylvania State University Press

is a member of the

Association of American University Presses.

It is the policy of The Pennsylvania State University Press to use acid-free paper. Publications on uncoated stock satisfy the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Material, ANSI z39.481992.

This book is printed on Natures Natural, which contains 50% post-consumer waste.

For Benjamin, Nicholas, and Matthew

CONTENTS

This book has been an unconscionably long time in the making. Consequently, I owe more than the usual debts of gratitude to the gentle prodding and prodigious patience of Peter Potter and Sandy Thatcher. I began the book while I was completing twenty wonderful years at the University of Virginia. My teaching, reading, writingand translatingwere complicated during my last years there by course overloads and an onerous, albeit important and satisfying, set of committee responsibilities. In January of 2001 I moved to Notre Dame to assume the directorship of the Medieval Institute. The years since my move have been the most rewarding of my professional life, but they have also been, by far, the busiest. Various duties, challenges, and responsibilities have continually nudged this book aside.

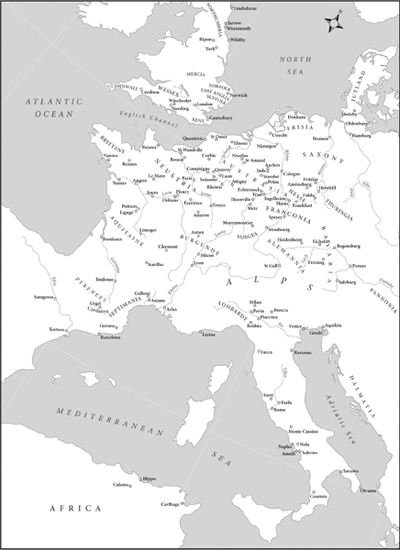

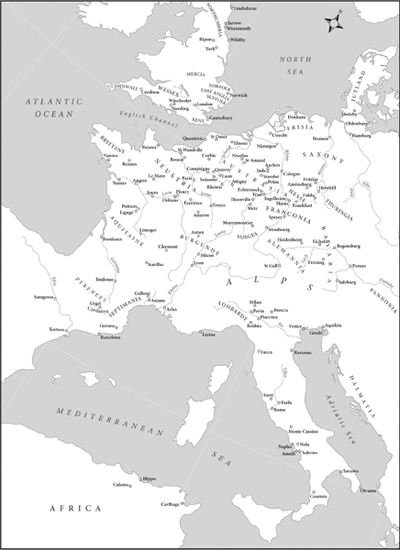

I have made very good use of the delays, however, by testing some of these translations on my students and by obtaining close readings of some of them by generous friends. My students in The World of Charlemagne have made numerous perceptive suggestions for improvement in The Life of Charles the Emperor. Julia Smith and Mayke De Jong read Thegan and the Astronomer in early drafts. Eric Goldberg gave Notker a finely attentive reading. Conversationsin person and via e-mailwith John Contreni, Paul Dutton, David Ganz, Paul Kershaw, Rosamond McKitterick, Jinty Nelson, Julia Smith, and the late Patrick Wormald have helped me in countless ways. Two research assistants, Katie Anne-Marie Carloss and Phil Wynn, deserve special thanks. I owe particular debts to Erin Greb, who drew the map that graces this book, and to Keith Monley, who edited a difficult text with sensitivity and imagination. My gratitude to students and colleagues is exceeded only by what I owe to my family. By the time I set to work in earnest on this book, my children were grown and married. This means at least two things. First, I owe more than ever to the patience and understanding of my wife, Linda. Second, the years when I was working on this book brought new joys into myinto ourlife, three grandsons, to whom I affectionately dedicate the volume.

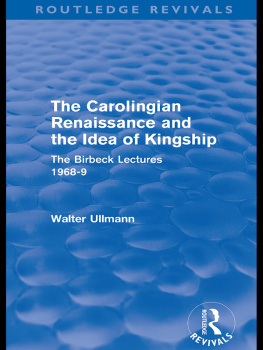

Carolingian history has long been a staple of teaching and research, but the numerous and impressive histories written by the Carolingians themselves are only recently coming into their own as serious subjects of investigation. To be sure, for more than two centuries scholars in many lands have scrutinized Carolingian sources for information about the Carolingian period. To their painstaking labors we own much of our basic picture of what happened in the eighth and ninth centuries. Nevertheless, the sources have usually been treated as great quarries from which the building blocks of narrative, documentation, and corroboration have been hewn. Until recently, with some notable exceptions, too little attention has been paid to the sources themselves in their own right and to their authors. It is also worth remarking, in a volume of English translations of Carolingian historical texts, that most of the old scholarship and much of the new exists in languages other than English. Undergraduates, beginning graduate students, and the elusive general reader who have no Latin are unlikely to read French, German, or Italian.

To be sure, source criticism of the solid, traditional variety can still sometimes bring important new insights. Two examples will suffice. Surely, one of the most familiar facts of Carolingian history is the famous question sent by Pippin III to Pope Zachary asking whether it was right that those in Francia who had the name of king had no power, while those who had power had not the name of king. Zachary allegedly responded that this situation contravened order, and soon thereafter Pippin was acclaimed as king by the Franks. Rosamond McKitterick has looked carefully at all the surviving evidence for this exchange and has come to the conclusion that it was a later Like McKitterick, Becher interprets a key source as constructing earlier historical narratives to serve later needs.

Still, what is most impressive about current research is the way that it looks at Carolingian histories as key sites for the exploration of ideology, political thought, social ideals, educational attainments, and their emulation of classical models, to mention only some prominent areas of investigation. It is clear that there were courtly and aristocratic audiences for history and that, in consequence, histories were often written to advance particular arguments or to promote particular individuals. In short, while details still matter, historians are learning to appreciate the artistry and intentions of the authors who provided us with those details.

Major early medieval historians such as Gregory of Tours (538/39590), Bede (673735), and Paul the Deacon (ca. 720ca. 800) did not write biographies but did create many memorable portraits of individual rulers, as well as of queens, holy men and women, bishops, and monks. Their works were certainly known in the Carolingian period, and their influences can occasionally be traced. Conditions at the dawn of the ninth century portended no stunning rebirth of secular biography, but that is exactly what happened. Indeed, biography has long been recognized as one of the brightest bands in the spectrum of Carolingian historical writing. That said, it is important to realize how novel and impressive was the achievement of the authors whose works are gathered together in this volume.

Next page

![Louis de Montfort - The Saint Louis de Montfort Collection [7 Books]](/uploads/posts/book/265822/thumbs/louis-de-montfort-the-saint-louis-de-montfort.jpg)