Contents

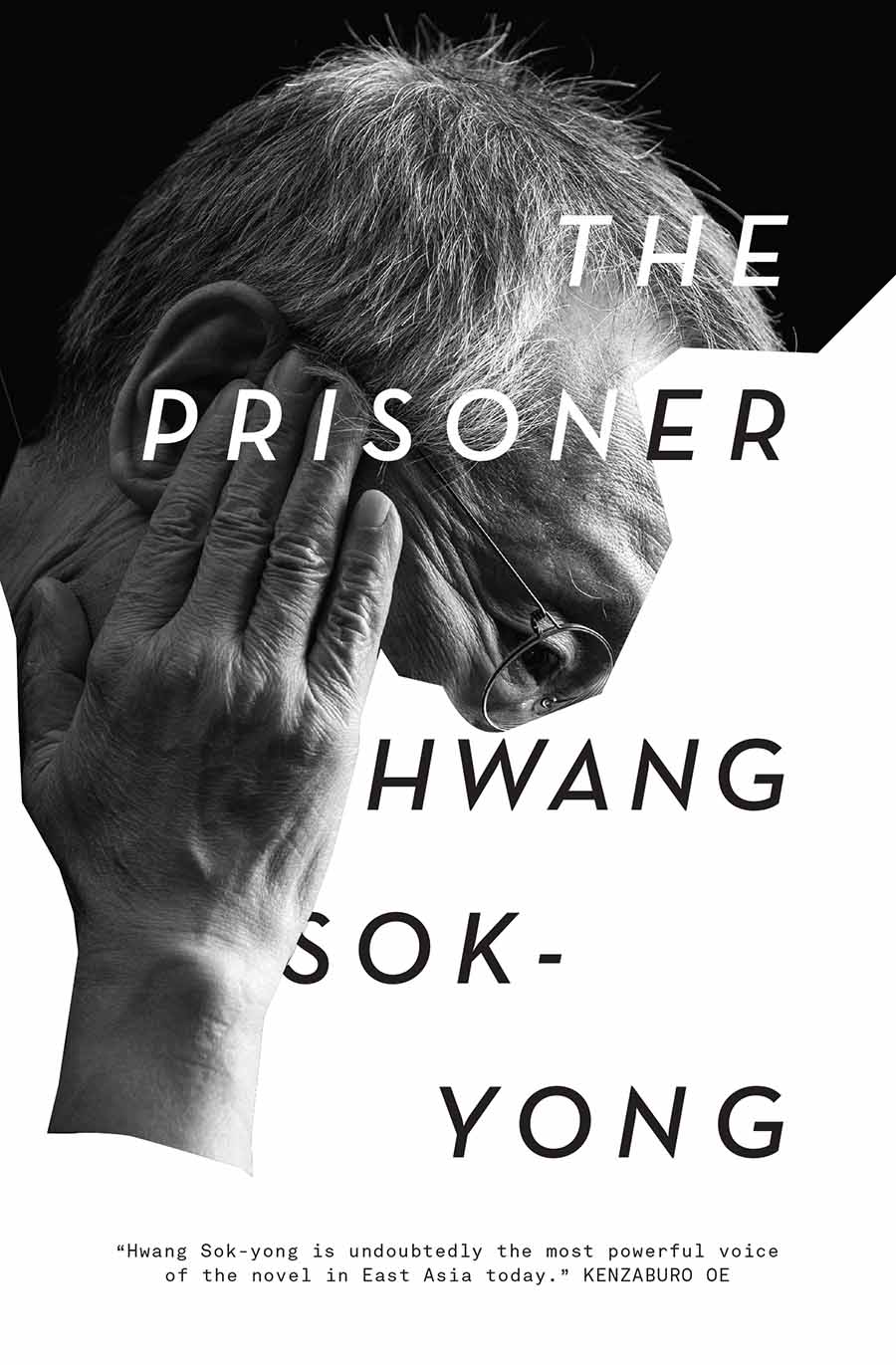

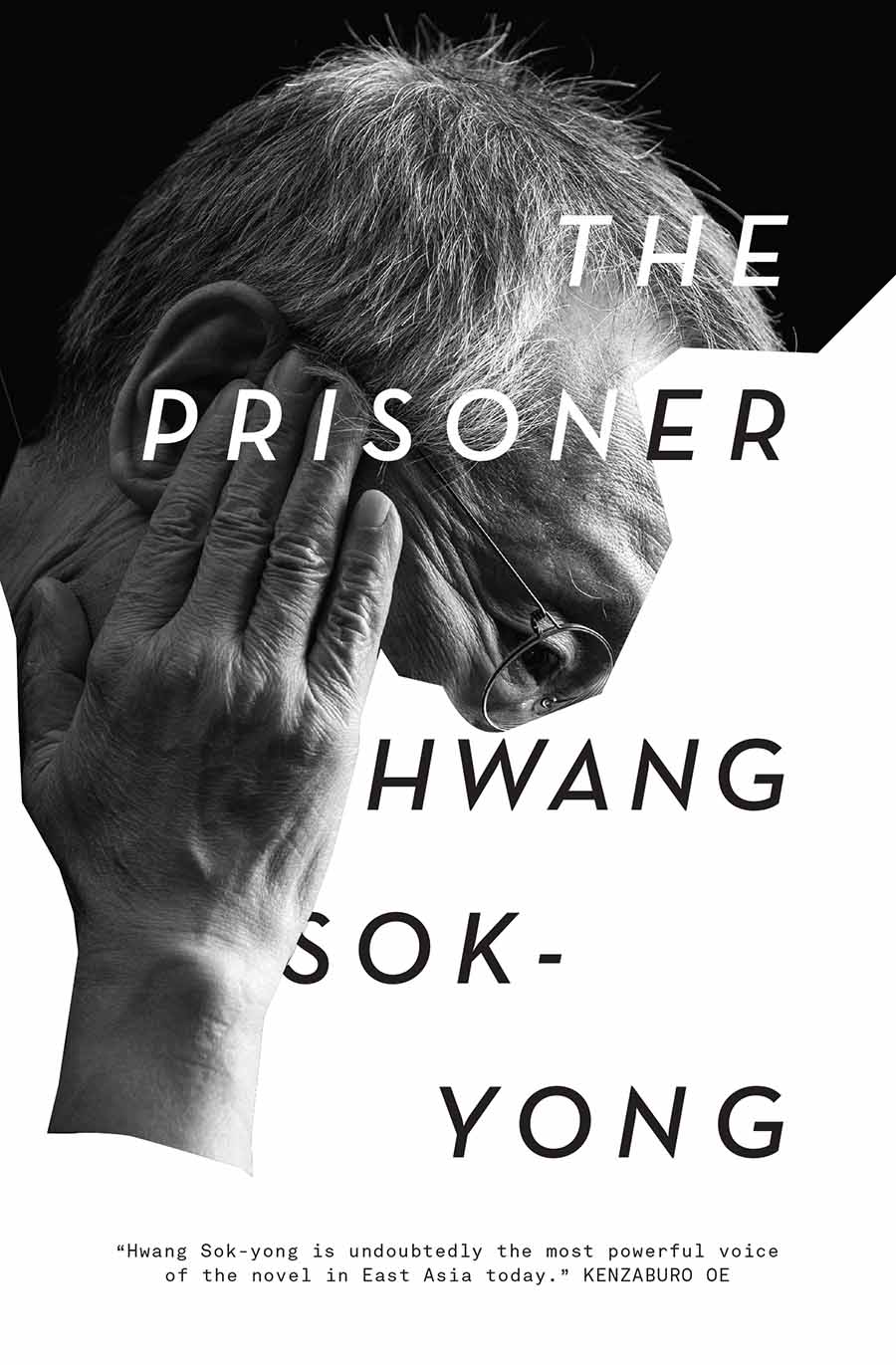

The Prisoner

The Prisoner

by Hwang Sok-yong

Translated by Anton Hur and Sora Kim-Russell

This book is published with the support of the Literature

Translation Institute of Korea (LTI Korea).

First published in English by Verso 2021

Translation Anton Hur, Sora Kim-Russell 2021

Originally published in Seoul, Korea, in two volumes:

(The Prisoner 1: Across the Border) and

(The Prisoner 1: Across the Border) and

(The Prisoner 2: Into the Fire)

(The Prisoner 2: Into the Fire)

Munhak 2017

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-083-9

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-085-3 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-086-0 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available

from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Sabon by Biblichor Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

Youre putting your fate in someone elses hands, said my mother, to discourage her son from becoming a writer. Your son as a young man wore you down, and now as an old man dedicates this book to you.

Contents

This book is published with the support of the Literature Translation Institute of Korea (LTI Korea), which the publisher gratefully acknowledges.

The short excerpt from Hwang Sok-yongs novel The Shadow of Arms is from the translation by Chun Kyung-ja, published by Seven Stories Press in 2014, and appears here with permission.

Readers should note that in order to bring the original two-volume Korean text into one English volume, this translation is a slightly shortened version of the text, abridged in collaboration between the author, translators, and editor. All Korean and Japanese names are set in the Asian style, that is, family name first and given name second.

I was eating my last lunch in the underground room. Not the usual cafeteria food on a tray but seolleongtang beef soup from a nearby restaurant. The head of the investigation, as he waited for me to finish, had divided thick reams of statements into manila envelopes to give to the Prosecutors Office. He began to speak.

Well all be going home at five on the dot once youre gone. Youve been through a lot here, havent you?

The investigator standing by him spoke up.

What do you think your sentence will be, sir?

I answered as if I were talking about someone else.

I dont know. Three years?

The head of investigation looked surprised.

Really? So little?

They give smaller sentences to the instigators than to the followers.

I must have been thinking about Moon Ik-hwan, the pastor who was pardoned after three years in jail, when I made that joke.

But youve gone to North Korea and met Kim Il-sung several times, so theyve got to put you away for at least seven or eight.

I replied again as if it were some other mans business.

Oh my, what a bother thats going to be.

Or maybe not. Isnt this meat and potatoes for you writers, your material, if you will?

The other investigator agreed.

We know youre going to write about us when you leave

You gentlemen sure know how to make me feel important.

I kept on joking, pretending to be unfazed. It was a skill Id mastered during their interrogations, an acquired habit of keeping my cool no matter what, so as to not lose in the battle of nerves. In the last few days, I was beginning to feel more like their coworker than a prisoner. These twenty days of the investigation by the Agency for National Security Planning (ANSP, formerly the Korean Central Intelligence Agency) were coming to an end, but I had only cleared the first of the gates of hell. Now I would be up against the Prosecutors Office.

I was never tortured. I was arrested several times during the Yushin dictatorship of the 1970s and once jailed for disobeying martial law declared after the assassination of President Park Chung-hee, but I never got so much as a slap across the face. Was I lucky, or were my stunts too tame to make it worthwhile? My fellow writer friends used to joke that one of these days my luck would run out and I would get my comeuppance. Thinking back, luck had something to do with it, but it probably helped that I was also a famous young novelist with a large, mainstream following, one who had serialized a saga titled Jang Gil-san every day for the past ten years in the pages of a daily.

When I was first arrested at the airport and dragged, blindfolded, to this underground room, the anti-communism investigators tried to intimidate me by shoving me into a corner and having a phalanx of investigators bark questions at me. A skinny man with piercing eyes cursed at me as he swung his fists. I had readied myself for this. I ducked the blows, pushed him away, and tore off my shirt.

What, the law isnt enough for you? Fine, torture me. Hit me!

The investigators tried to calm the other man down and pulled him away, calling him Siljangnim, which allowed me to guess that he was the section chief. I still remember what he said to me before he left.

You bastard, you think the world has changed? You think all you got to do is bullshit a little and well let you go? Were gonna flay the skin off your ass!

The painter Hong Seong-dam was once arrested and severely tortured for sending slides of his murals to the World Festival of Youth and Students in North Korea. He later drew a portrait of his torturer and published it in a newspaper; it turned out to be the same face as my own would-be torturer.

But whenever an investigator tried to use their usual violent tactics against me, another would stop him.

Hurting him is more trouble than its worth.

On my first day at the ANSP headquarters, I had been asked to take off my clothes. I looked askance at the investigator before removing my shirt.

Do I have to take it off for you? Strip!

The irritation in the investigators voice made me tense at the thought that the torture was about to begin. I reluctantly took off my pants. Another investigator standing by tossed a military uniform on a chair and left with my clothes. I gritted my teeth and proudly stood up straight while the remaining investigator looked on indifferently.

Youll get your clothes back when you leave. Put those on for now.

I put on the worn, loose army uniform. In the middle of my first interrogation, I was dragged into the corridor and made to stand with a sign that had my citizens registration number on it as they took my picture. A doctor came down to the interrogation room and performed a quick checkup. I had to stamp my thumbprint on numerous documents saying that I agreed to everything I was subjected to and that I would take sole responsibility for whatever happened. I had expected verbal abuse and humiliation to be part of the investigation process, but what was unbearable was the lack of sleep. Scores of investigators took turns questioning me in groups of three or four, and for the first few days I was confused by the hourly flow of new faces. Whenever there was a change in investigators, the questions started over from the beginning. The walls and ceiling of the interrogation room were of perforated soundproofed particleboards, and there was a desk, four chairs, a military-issue cot in the corner, and a bathroom. As time went on, I learned that the interrogations were also being watched from the outside. I realized this when I happened to say something inconsistent in my statement, and a higher-up came running into the room to hound me about it. There were some fluorescent lights on the ceiling and a vent, as this was underground, but the lack of windows made it impossible to tell whether it was night or day. There was, of course, nothing like a clock. All I could do was measure the hour by the fatigue on the investigators faces and guess at how many days had passed. Sometimes, when I went into the bathroom and dozed off on the toilet, an investigator came in and dragged me back to my chair. More than once, someone clasped me by the shoulders and gently rocked me, saying, What a pity if something terrible were to happen to this important person, before waving his fist in the air as if nothing would make him feel better than to let it fly into my face.

(The Prisoner 1: Across the Border) and

(The Prisoner 1: Across the Border) and (The Prisoner 2: Into the Fire)

(The Prisoner 2: Into the Fire)