Contents

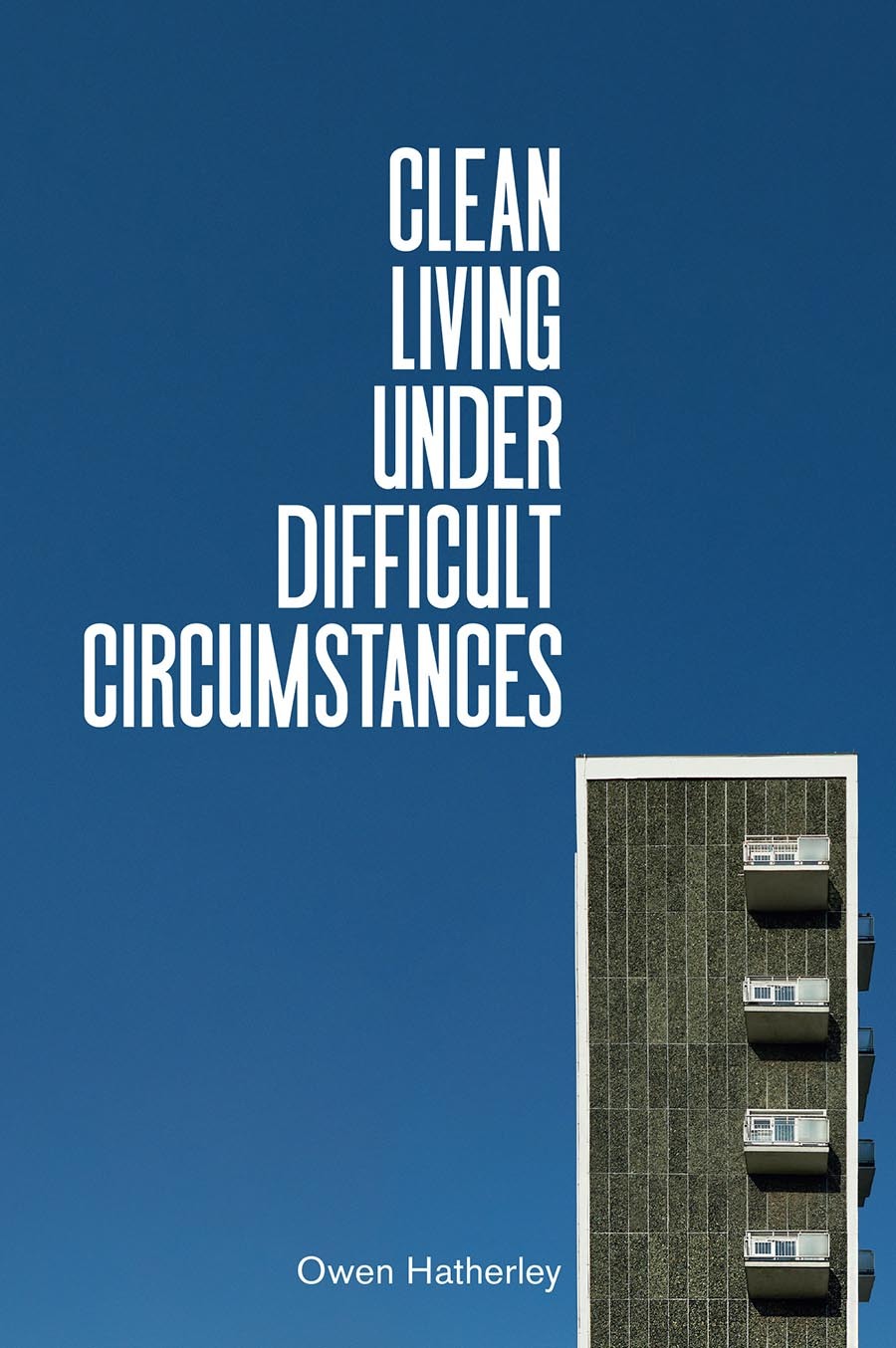

Clean Living under

Difficult Circumstances

Clean Living under

Difficult Circumstances

Finding a Home in the

Ruins of Modernism

Owen Hatherley

First published by Verso 2021

Owen Hatherley 2021

The publisher and author express their gratitude to the publications in which some of the essays republished here first appeared. Complete details of prior publication can be found in the acknowledgments.

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-221-5

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-224-6 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-223-9 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hatherley, Owen, author.

Title: Clean living under difficult circumstances: finding a home in the ruins of modernism / Owen Hatherley.

Description: Brooklyn, NY: Verso, 2021. | Summary: In this essay collection, essayist and author Owen Hatherley outlines a vision of the modern city as both a venue for political debate and a space for everyday experience the city as a socialist project Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021001634 (print) | LCCN 2021001635 (ebook) | ISBN 9781839762215 (hardback) | ISBN 9781839762246 (US ebk) | ISBN 9781839762239 (UK ebk)

Subjects: LCSH: City planning Environmental aspects Great Britain. | Housing Great Britain. | Sound Environmental aspects Great Britain. | Socialism Great Britain.

Classification: LCC HT169.G7 H386 2021

(print) | LCC HT169.G7 (ebook) | DDC 307.1/2160941 dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021001634

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021001635

Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed in the US by Maple Press

Nowadays, complained Mr K, there are innumerable people who boast in public that they are able to write great books all by themselves, and this meets with general approval. When he was already in the prime of life the Chinese philosopher Chuang-tzu composed a book of one hundred thousand words, nine-tenths of which consisted of quotations. Such books can no longer be written here and now, because the wit is lacking. As a result, ideas are only produced in ones own workshop, and anyone who does not manage enough of them thinks himself lazy. Admittedly, there is not then a single idea that could be adopted or a single formulation of an idea that could be quoted. How little all of them need for their activity! A pen and some paper are the only things they are able to show! And without any help, with only the scant material that anyone can carry in his hands, they erect their cottages! The largest buildings they know are those a single man is capable of constructing!

Bertolt Brecht, Originality, from Stories of

Mr Keuner (trans. Martin Chalmers)

Contents

In the spring of 2005, I began to self-publish a blog, about modern architecture, modern design, cities, music, TV, film, politics whatever interested me at the time. When I started it, I was hiding from various things and various people at my mothers flat in Northam Estate, a public housing scheme near the centre of the city of Southampton, a port on the South Coast of England. This was the first time, at the age of twenty-three, that I had ever lived in housing that could clearly be described as modernist. Growing up in a city whose centre was flattened in the Second World War, I had always been surrounded by, and fascinated with, high-rises, glass office blocks, concrete walkways but I had until then lived in Victorian terraces or early twentieth-century suburbs. Northam Estate was a little worn out and had a few tacky little signs and fences added, but its clarity as a design was unaffected.

It was built in the late 1950s by Southampton Corporation Architects Department, then one of the most powerful and prolific in Britain. The estate replaced an area of Victorian and Georgian slums, a dense dockside district mainly inhabited by dockers and the crew of White Star Line ships; 350 people from Northam lost their lives when the Titanic sank. Like most of Southampton, the area was heavily bombed in 1940, with that damage compounding the poor quality of the housing. Belatedly, it was all suddenly swept away fifteen years later, and replaced with around twenty four-storey blocks and one sixteen-storey tower, placed in irregular arrangements, oriented to the sun, surrounded by trees, but close enough to the river to hear foghorns. The buildings themselves were spacious, bright, with polychrome brickwork, big windows and balconies, and secluded from the main roads. A sanctuary.

York House, Northam Estate

Our circumstances were not quite so drastic as those of the people who first moved into these blocks, but they are easily described as difficult. The route that took me there, with my mother, my brother James and my sister Frances, was circuitous. In the 1990s my mother, who had left school at sixteen, trained as a teacher, taking night classes to get A-levels, a degree and a PGCE. To pay her way through this, she sold her house in Eastleigh, a railway town just outside Southampton, and rented an exlocal authority house in the suburban Flower Estate, a low-density 1920s garden suburb of houses and large gardens, laid out in the hope that dockers would grow their own vegetables. After a while she found teaching and single-motherhood an impossible combination and quit her job at the estates primary school. After a spell of unemployment, she was put on something called the New Deal , which entailed working for her dole at a local cancer charity. Unable to pay the rent, she was evicted. Southampton City Council who I could fault for all manner of other things rehoused her, first in temporary accommodation for a few months, then in a flat in Northam Estate. Council housing was once supposedly for everyone from the doctor to the milkman to the miner, in Aneurin Bevans phrase but even in 2000, one could rely on the council to house a one-parent family that had been made homeless, and house them well. After what felt like years of struggle different rented houses, temporary jobs getting this flat allowed Mum the space and time to put her life back together.

My path there had been a little different. A year before Mum, James and Frances were evicted, I had already left for university specifically, Goldsmiths College. Starting in 1999, I was in the first cohort to receive no maintenance grant and to have to pay tuition fees. My fees were being paid for me again, by Southampton City Council, thanks comrades but I had fully expected, my mind addled with books about 1968, to arrive at a hotbed of student occupations and marches. Blur, alumni of the college, had even played at an occupation in protest at the introduction of fees the year before! It did not work out like this. I dont think there was a generation between 1945 and the present day that was so politically quietist as that born in the 1970s and early 1980s, yet somehow I hadnt realised this: not only were both my parents card-carrying Marxists (who had for some decades also been card-carrying members of the Labour Party); also various coincidences meant my friends at school had parents who were more often socialists than not. So, intoxicated by the delusion that Id be entering the Sorbonne in May 68, or at least Hornsey Art College, I was brought quickly down to earth as I realised that most people I was studying with were not there to build a new society out of the ashes of the old, or even to experiment with new lifestyles or ideas; instead, they were attending out of a peculiar kind of middle-class obligation, taking part in a rite of passage of cider and absinthe, virginity-loss, food fights, Gomez records, socs and ents. I viewed this with corrosive inverted snobbery, which I suspect made me quite insufferable. Given that my immediate family were being made homeless at the time, perhaps some of my scorn can be forgiven.