Contents

Guide

2021 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

The MIT Press would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who provided comments on drafts of this book. The generous work of academic experts is essential for establishing the authority and quality of our publications. We acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of these otherwise uncredited readers.

This book was set in Freight and Halyardtypefaces designed by Joshua Dardenby the MIT Press.

Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from the Wyeth Foundation for American Art Publication Fund of CAA.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Campt, Tina, 1964 author.

Title: A black gaze : artists changing how we see / Tina M. Campt.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The MIT Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020037098 | ISBN 9780262045872 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Aesthetics, Black. | Arts, Black21st century. | Arts and societyHistory21st century.

Classification: LCC BH301.B53 C36 2021 | DDC 704.03/96073dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020037098

10987654321

d_r0

To AJ, who opened the door,

and Saidiya, who pushed me through...

Verse One

The Intimacy of Strangers

I had made only one studio visit prior to my arrival at Deana Lawson's Brooklyn studio on a blustery August afternoon. Truth be told, I'm still not quite sure what a studio visit is supposed to look like, and on that day, I was pretty nervous about the fact that the artist herself would be there watching me and my curious way of writing. It's a method of writing Lawson herself gave me words for when she invited me to visit, describing it as a studio practice of writing.

Rather than writing about artworks, I spend most of my time at exhibitions and galleries sitting with and writing to them. I write to them about the feelings they solicit, the forms of discomfort they evoke, the emotional work they require and often demand, and the potentially transformative effects they have when we allow ourselves to inhabit those feelings and responses. So, as I said, I was nervous about what felt like my very first official studio visit. My fears turned out to be needless, for my visit to the studio of one of the most daring photographers of our current moment was nothing less than exhilarating. Much to my surprise, when I checked my email the next morning, I found she had written me a thank-you note, when of course, it was I who really needed to thank her. But I had to chuckle at her opening lines.

Thank you for taking the time to visit the studio today. It was my first meeting where the visitor wrote in silence on the floor at the beginning. It was nice to observe your writing/thinking process.

Seated cross-legged on the floor is my go-to position for writing to art. There was a time when I was self-conscious about it. But after years of yielding to gravity to create a personal cone of silence so I could take in the full impact of art in spaces that frequently militate against the forms of lingering and observing required to truly grapple with work that is difficult to come to grips with in the space of a gallery or museum, I have no compunction about sliding down a wall and claiming the undervalued real estate of a gallery floor.

Writing to artwork from the floor of a gallery (or, in this case, an artist's studio) minimizes you as a viewer and maximizes the work itself. Looking up at it both breaks up and breaks down some of the traditional dynamics of spectatorship and visual mastery. And when the subject of that art is Black folks, challenging the dynamics of spectatorship and visual mastery is an extremely important intervention.

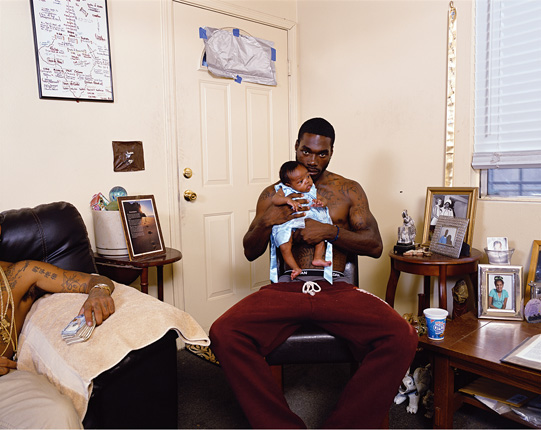

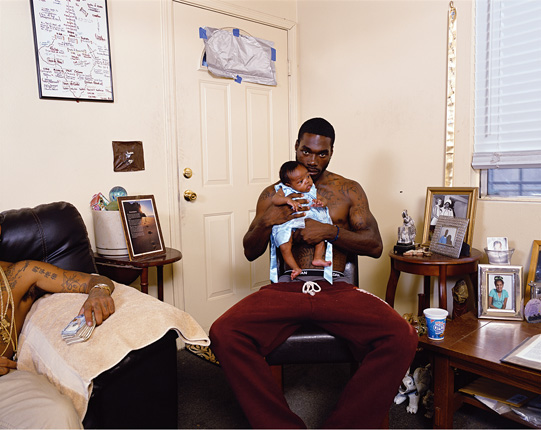

Deana Lawson, Sons of Cush (2016)

A muscular young Black man paired with a partial view of a companion who shares the space seated next to him on a couch. They occupy a tiny front room packed with furnishings, objects, and images that fill the compact space of a home that seems almost too small for its occupants. One man cradles an infant in his oversized hands; the other flashes an oversized wad of cash in an equally oversized hand.

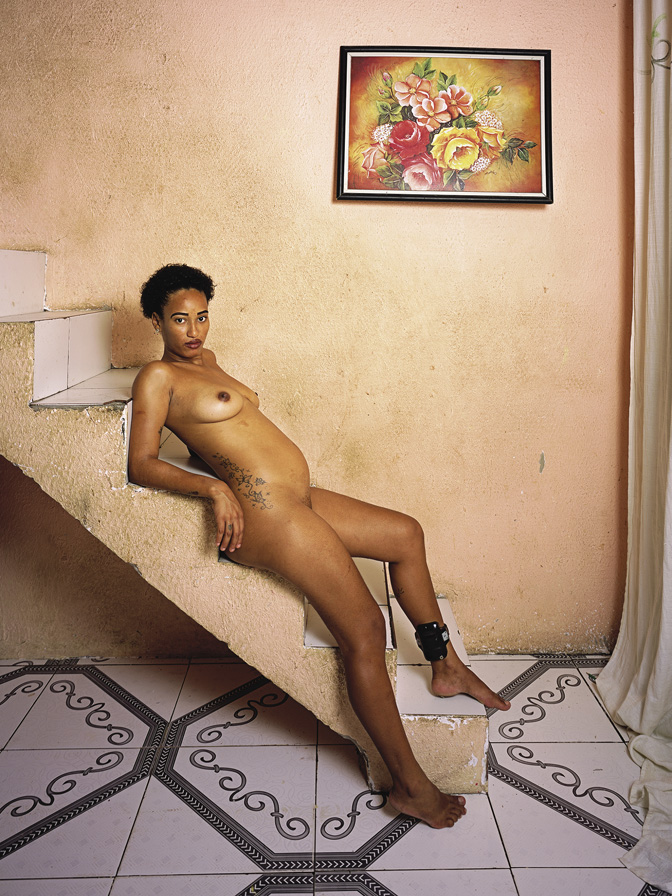

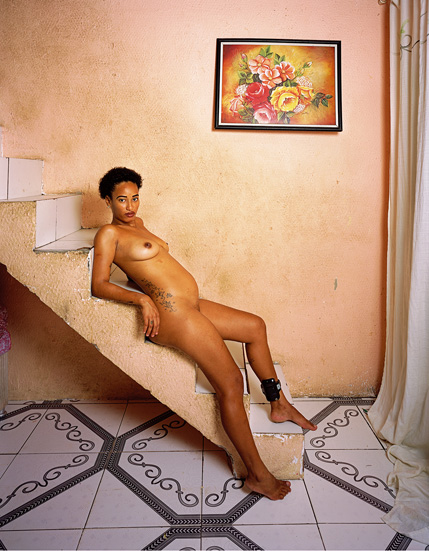

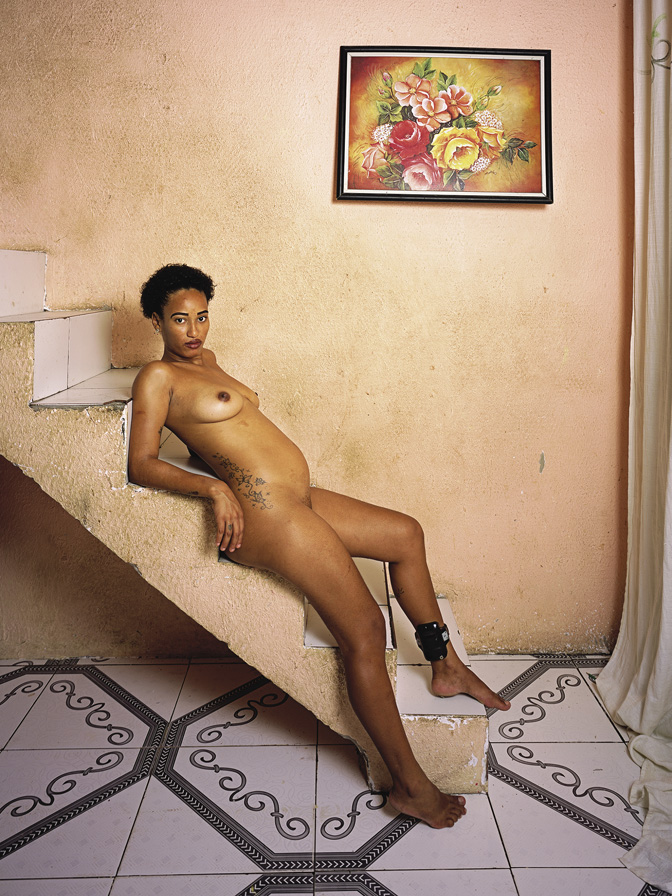

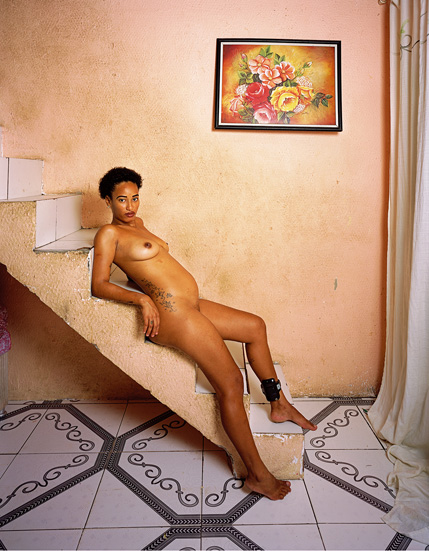

Deana Lawson, Daenare (2019)

A nude, bronze-skinned, Brazilian woman lies in the classic repose of a nineteenth-century odalisque. She drapes herself over salmon-colored concrete steps against the backdrop of identically colored walls. Snaking from waist to thigh is a tattoo that guides our gaze past a nascent baby-bump and down her long legs to rest on an ankle shackled by a strap and the unmistakable metal box of an electronic monitoring device.

Deana Lawson, Taneisha's Gravity (2019)

An older Black woman in a cherry red suit perches on the arm of one of two massive and clearly over-loved couches in Rochester, New York. On the couch to her right sits the matching accessory to her fabulous ensemble: an extravagant red hat befitting a treasured matriarch or dedicated church lady. Seated to her left and sharing the couch on which she perches, her daughter nods off peacefully beside her.

These were some of the images that hung on the walls of Lawson's studio on the day of my visit. But before I sat and wrote to them, they insisted that I walk with them. They are photos that beckon us to travel with and alongside them. They cannot be engaged passively; they demand an encounter. As I stood before them, as I walked and lingered in, between and among them, I felt them watching metaking me in and taking me into the spaces of their homes through the stairways, hallways, and rooms they inhabited and traversed. They are images that beckon you into their places of work in the club, on the street, or somewhere else altogether. Lawson's photographs draw us into a world of strangers to whom we feel intimately connected.

Perhaps it's their scale that makes them register so intensely. The photographs Lawson had on display were huge. She told me she had been encouraged by Los Angeles artist, activist, and founder of the Underground Museum, Noah Davis, to go big, and that his words had inspired her to expand the size of her prints from the typical scale of framed gallery prints to expansive tableaus. In doing so she transforms the Black subjects captured in their frames into life-sized simulacra that force us to meet them as equals. Writing to her images from the floor of her studio, encountering them from the bottom up, seated at their feet, gave me a necessary sense of humilityhumility in relation to Black men and women whose unrelenting gazes ricocheted palpably around the room. While Lawson and I were the only people in the studio, the intensity of their presence made it feel as if we were in the middle of a very crowded space.