Contents

Guide

ALSO BY REBECCA CARROLL

Uncle Tom or New Negro?: African Americans Reflect on Booker T. Washington and Up from Slavery 100 Years Later (ed.)

Saving the Race: Conversations on Du Bois from a Collective Memoir of Souls

Sugar in the Raw: Voices of Young Black Girls in America

Swing Low: Black Men Writing

I Know What the Red Clay Looks Like: The Voice and Vision of Black Women Writers

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2021 by Rebecca Carroll

Certain names and identifying details have been changed. Others, like members of my adoptive family, my immediate family, my birth father, and my day ones, are their true names.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition February 2021

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Ruth Lee-Mui

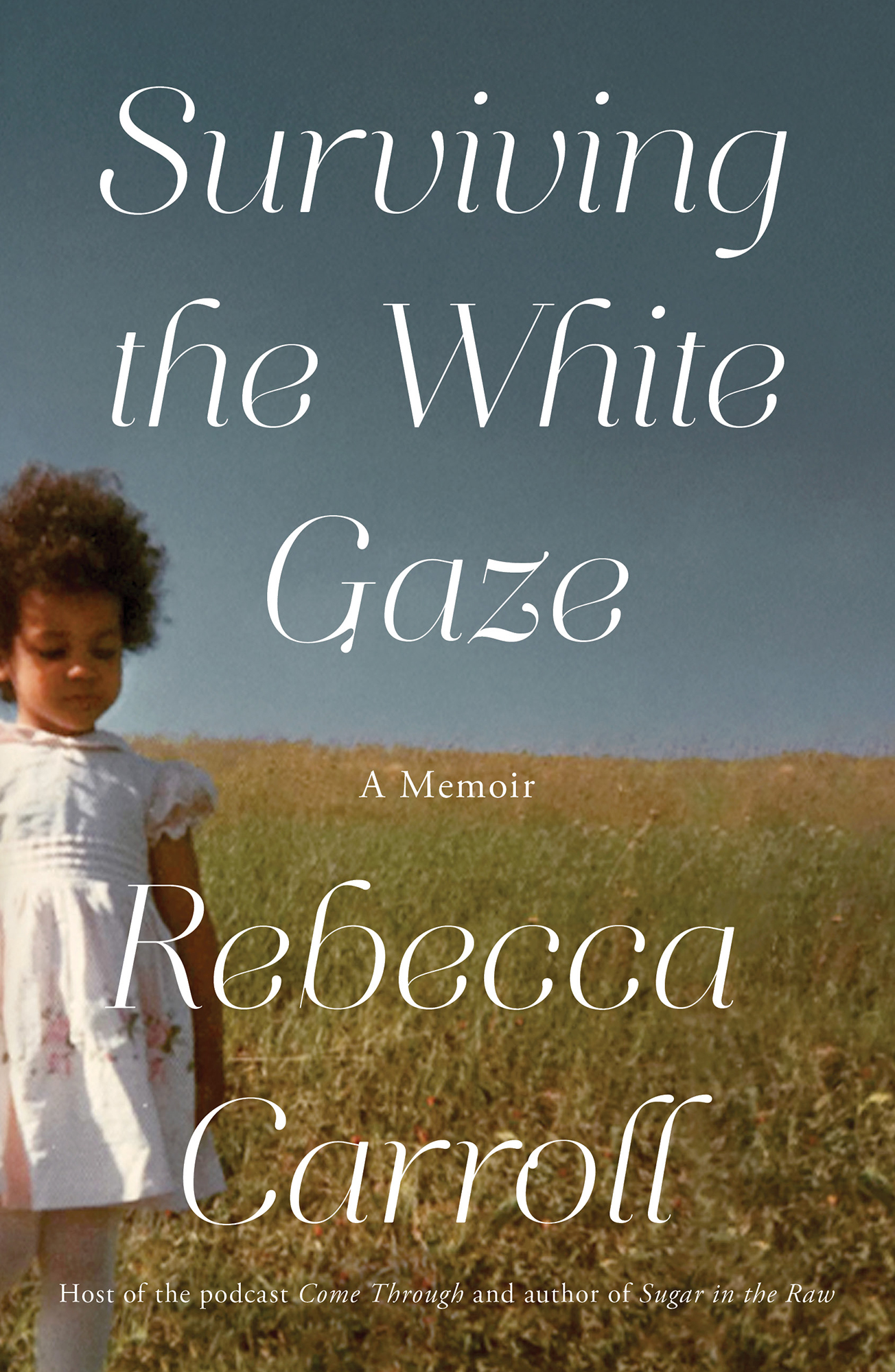

Jacket design by Math Monahan

Jacket photograph courtesy of the author

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Carroll, Rebecca, author. Title: Surviving the White Gaze : A Memoir / Rebecca Carroll. Description: First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition. | New York : Simon & Schuster, 2021. | Identifiers: LCCN 2020029852 (print) | LCCN 2020029853 (ebook) | ISBN 9781982116255 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781982116279 (paperback) | ISBN 9781982116323 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Carroll, Rebecca. | Interracial adoptionNew HampshireWarner (Town) | Adopted childrenNew HampshireWarner (Town)Biography. | Race awareness in childrenNew HampshireWarner (Town) | Racially mixed familiesNew HampshireWarner (Town) | African American women authorsBiography. | African AmericansRace identity. Classification: LCC HV875.65.N47 C37 2021 (print) | LCC HV875.65.N47 (ebook) | DDC 305.48/8960730092 [B]dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020029852

ISBN 978-1-9821-1625-5

ISBN 978-1-9821-1632-3 (ebook)

For Kofi

Prologue

W hen I was writing this book, I asked a few friends, family, and former students to share memories if they were inclined, from when we first met or of experiences that stood out for them. This note came from Felicia, who was among the handful of black students I had at an all-girls private school outside of Boston, where I taught ninth grade English and eleventh grade history for the 19951996 academic year, when I was twenty-five and she was sixteen.

There are gaps in my memory from my childhood. I cant tell you if this was my sophomore year or my junior year, but my memory of the first time meeting you is this: You asked us to write a memory from our summer. That summer was my first time being in jail. My paragraph or two recounted how I had run from the Boston Police after being tracked down for running away from home. Im sure my classmates wrote of travels abroad or time with family and friends.

But mine was different. Home at that time was unbearable. I was unbearable. But you asked. And no one had ever cared to ask. And you looked like me. So I told you about how I had almost out run them, and then how my wrists were too small for the handcuffs after they caught me. I went to court and then to the foster home. But very neatly by the time school started, I was back home and in my private school and in your class. You were my first black teacher ever and you were the light.

This is what black folks are to one anotherwe are the light that affirms and illuminates ourselves to ourselves. A light that shines in its reflection of unbound blackness, brighter and beyond the white gaze. The path to fully understanding this, and my ultimate arrival at the complicated depths of my own blackness, was a decades-long, self-initiated rite of passage, wherein I both sought out and pushed away my reflection, listened to the wrong people, and harbored an overwhelming sense of convoluted griefa grief that guided me here, to myself.

One

I m gonna put chocolate chips in mine, I chirped, scrambling to gather up a handful of small dark pebbles to mix into my mud pie. The mucky mound was fast losing its shape inside the long, narrow tire grooves of our dirt driveway, still wet from rain the day before. The sky was a faint azure blue, and the sweet, powdery fragrance of milkweed wafted in the distance. And some sprinkles, I said, adding a few strands of freshly tugged grass from the lawn nearby, cool in my hand on a warm summer morning.

Leah, my best friend, barely looked up, so intently absorbed in the creation of her own mud pie, rounding it with her fingers to perfection. Even at four years old, she was detail-oriented and meticulous, a budding artist who took her work very seriously, while I at four had more of a collagist approach to things: the more elements and textures and ingredients, the better. When Leah was finished with her pie, she found a thin twig to outline a pattern on the topnot as simple as a plain lattice like the apple piecrusts Mom made, but tiny squares and triangles and circles interconnected, similar to a design in the pages of one of the thick art books lying around our house, and hers, too.

Leahs mom, Hannah, was a good friend of Mom and Dad. She had come over with Leah in the morning and visited with Mom for a little while as we played before doing some tai chi in the front yard. After a couple of hours, it was time to go. Leah and I hugged our goodbyes, her soft white wisp of a body fixed inside my bare brown arms, as the sun started to stretch high into the afternoon above the trees and beyond our wide-eyed, handmade world. Bye! we simultaneously trilled into each others ears. OK, girls, Hannah said, smiling at the closeness wed nurtured from when we were babies lying on a blanket together, reaching for each others fingertips. Well get together again soon, OK? Bye, Laurette! Mom waved goodbye to Hannah and Leah from where she stood, leaning against the worn wooden doorjamb of our country farmhouse.

Warner, the New Hampshire town where we lived, had a population of approximately 1400 when we moved there in 1969, and I became its sole black resident. We rented our farmhouse from longtime Warner residents who owned a lot of land and property in town. The house sat on the top of a dirt road called Pumpkin Hill, which was lined up and down by a dilapidated stone wall of various-sized rocks and stones, leading into different parts of town on either side. There was a shed connected off the right of our house, and a giant freestanding barn to the left, separated from the house by the wide driveway where Leah and I had played that morning. An apple tree with rugged, splayed branches good for climbing stood planted squarely in the front yard. Not another house in sight, nor a neighbor within earshot.

Prologue

Prologue