ALSO BY REBECCA CARROLL

Saving the Race: Conversations on Du Bois from

a Collective Memoir of Souls

Sugar in the Raw: Voices of Young Black Girls in America

Swing Low: Black Men Writing

I Know What the Red Clay Looks Like:

The Voice and Vision of Black Women Writers

Published by Harlem Moon, an imprint of Broadway Books, a division of Random House, Inc.

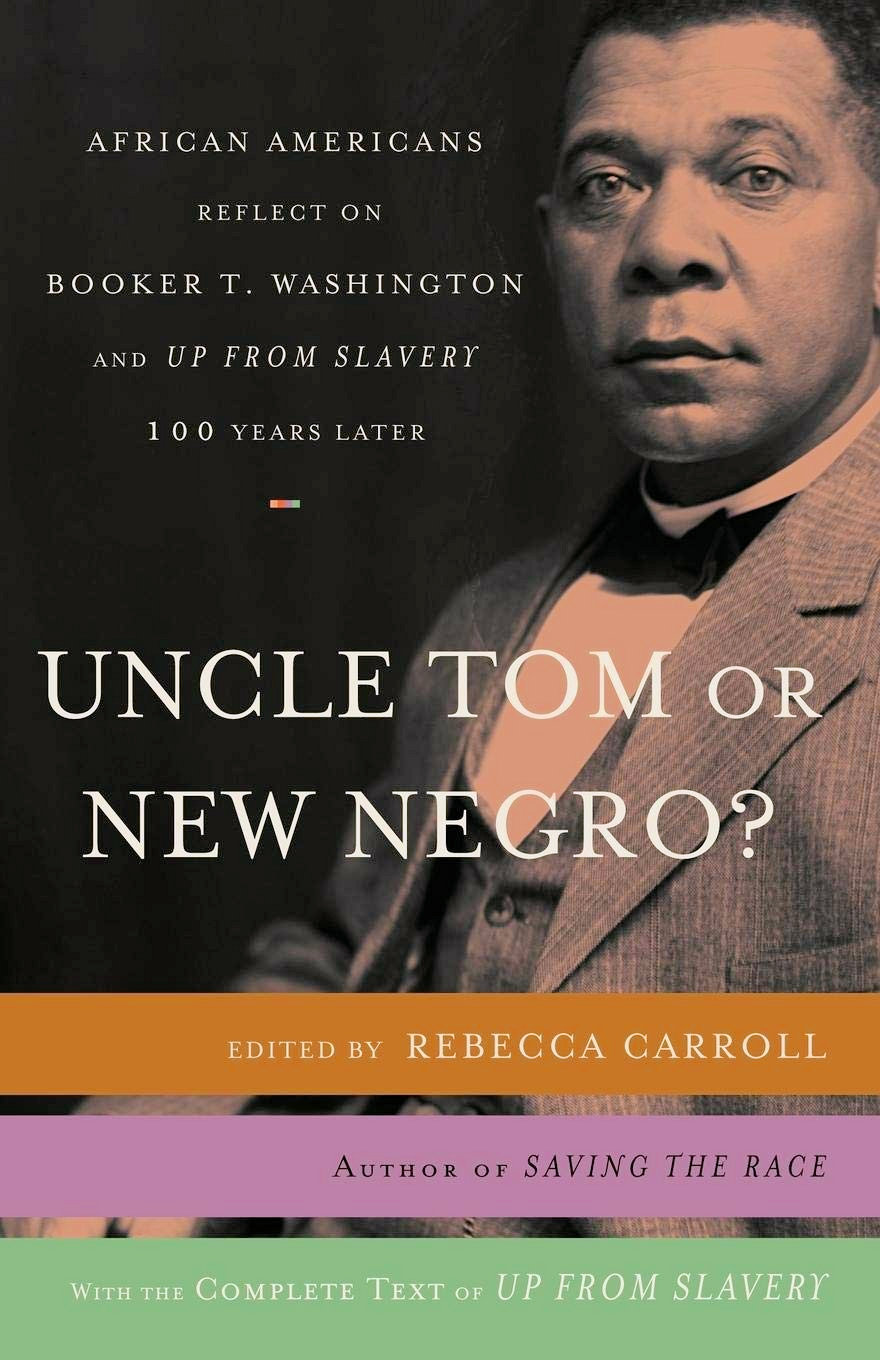

UNCLE TOM OR NEW NEGRO? copyright 2006 by Rebecca Carroll.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. For information, address Broadway Books, a division of Random House, Inc.

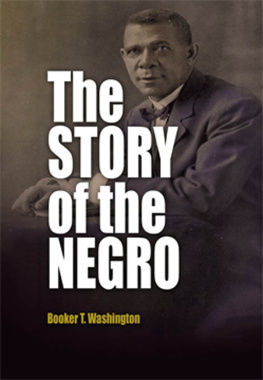

UP FROM SLAVERY was originally published in 1902 by Doubleday.

HARLEM MOON , B ROADWAY BOOKS , and the HARLEM MOON logo, depicting a moon and a woman, are trademarks of Random House, Inc. The figure in the Harlem Moon logo is inspired by a graphic design by Aaron Douglas (18991979).

Visit our website at www.harlemmoon.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Uncle Tom or new Negro : African Americans reflect on Booker T. Washington and Up from slavery 100 years later / edited by Rebecca Carroll.

p. cm.

1. Washington, Booker T., 18561915. 2. Washington, Booker T.,

18561915. Up from slavery. 3. African AmericansBiography.

4. EducatorsUnited StatesBiography. I. Carroll, Rebecca.

II. Washington, Booker T., 18561915. Up from slavery.

E185.97.W4U53 2006

370.92dc22

2005050161

eISBN: 978-0-307-41953-8

v3.1

For Chris, because theres very little that isnt

CONTENTS

for Uncle Tom or New Negro?

UP FROM SLAVERY

Complete text with a new Editors Note follows .

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book would not be possible without the ongoing support and encouragement of my editor, Janet Hill, who continues to find my ideas interesting and makes them even more so with her careful guidance and dedicated insights. Much thanks to Meredith Bernstein, my agent of more than ten years who would do her enthusiastic best to sell a book on my behalf about polar bears and gas stations if thats what I felt most passionate about. Love and appreciation to my parents, whose creative and artistic influence is omnipresent in all of my workin my life and everything I do. And finally, endless thanks to my husband, Chris Bonastia, who never fails to read whatever I write with anything other than a championing spirit and an engaged mind.

UNCLE TOM

OR

NEW NEGRO?

INTRODUCTION

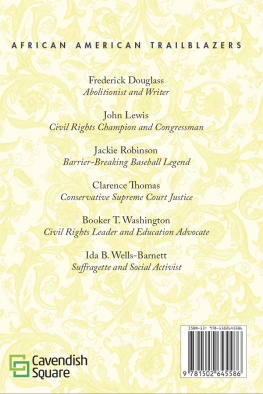

W HEN I FINALLY read Up from Slavery in its entirety as an adult, it was the second or third time the book had been assigned or recommended to me. I had started reading it the other times but had never felt gripped or engaged by Washingtons writing. His story was justly remarkable, but not extraordinary; many former slaves had gone on to become great educators and activists and writers. Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, Ida B. Wells, Sojourner Truthall had been slaves, all had made outstanding examples of their freedom, and all, it seemed, were better and more compelling writers than Booker T. Washington. That I felt behooved to judge the quality of writing more than the actual content is indicative of my generations relative insulation from the anguish and reality of slavery.

What I did not appreciate then but understand now after rereading Up from Slavery again as an adult is that what makes Washington and this book extraordinary is in fact how ordinary it is, how evenhanded, poised, and frank a personal account he crafted for publication in 1901, a time when learning how to read and write was still a life-threatening endeavor for black people. Furthermore, the style and tone of Washingtons writing, while perhaps not poetically striking, do succeed in mirroring its message in near-precise measure. Humility, consistent hard work, attentive behavior, and great faith in humanity can well set the foundation for a strong sense of self and the achievement of individual sovereignty. Every persecuted individual and race should get much consolation out of the great human law, which is universal and eternal, that merit, no matter under what skin found, is, in the long run, recognized and rewarded. This I have said here, not to call attention to myself as an individual, but to the race to which I am proud to belong.

But possibly even most important, Booker T. Washingtons Up from Slavery is a human legacy in narrative form. For someone who did not grow up with parents passing down or referencing stories of African American history and folklore, and maybe also for those at that awkward point of generational disconnect where everything back then seems so irrelevant and annoying, Up from Slavery is a poignant primer not because it has been called by jacket flap copywriters one of the greatest American autobiographies ever written, but because it is the very embodiment of legacy, something that has been handed down from the past from an ancestor. Years ago, writes Washington within the first thirty pages of Up from Slavery, I resolved that because I had no ancestry myself I would leave a record of which my children would be proud, and which might encourage them to still higher effort.

Much has been made in todays vernacular, and indeed discussed in this books narrative interviews, of the notion that Washington was an Uncle Tom, a term and stereotype that find their origin in the docile and dutiful Uncle Tom character of the classic novel Uncle Toms Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe, in which Uncle Tom is a fairly intelligent man, if without formal education. It is a curious notion, as the Uncle Tom stereotype has become primarily qualified by a passive nature, if also by an eagerness to please white people. Booker T. Washington was certainly many things, but he was not passive. One cannot serve as founder of an institution (at twenty-five years of age), raise hundreds of thousands of dollars for that institution, serve as adviser to United States presidents and congressmen (in the postslavery Reconstruction era), or preach the value and necessity of human progress and self-reliance whilst being passive in nature.

But over the years passive became house nigger became spineless and finally became sellout. In some ways it seems there is a kind of involuntary reflex among African Americans, particularly in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, to brand one of our ownusually one of our famed ownas an unforgivable sellout. From Clarence Thomas to Colin Powell and Henry Louis Gates, black people (most often men) who negotiate with white people are frequently labeled sellouts no matter what they are selling. Men who, for better or worse, as leading black British scholar Stuart Hall was once quoted as saying of Gates in a 2002 article for the