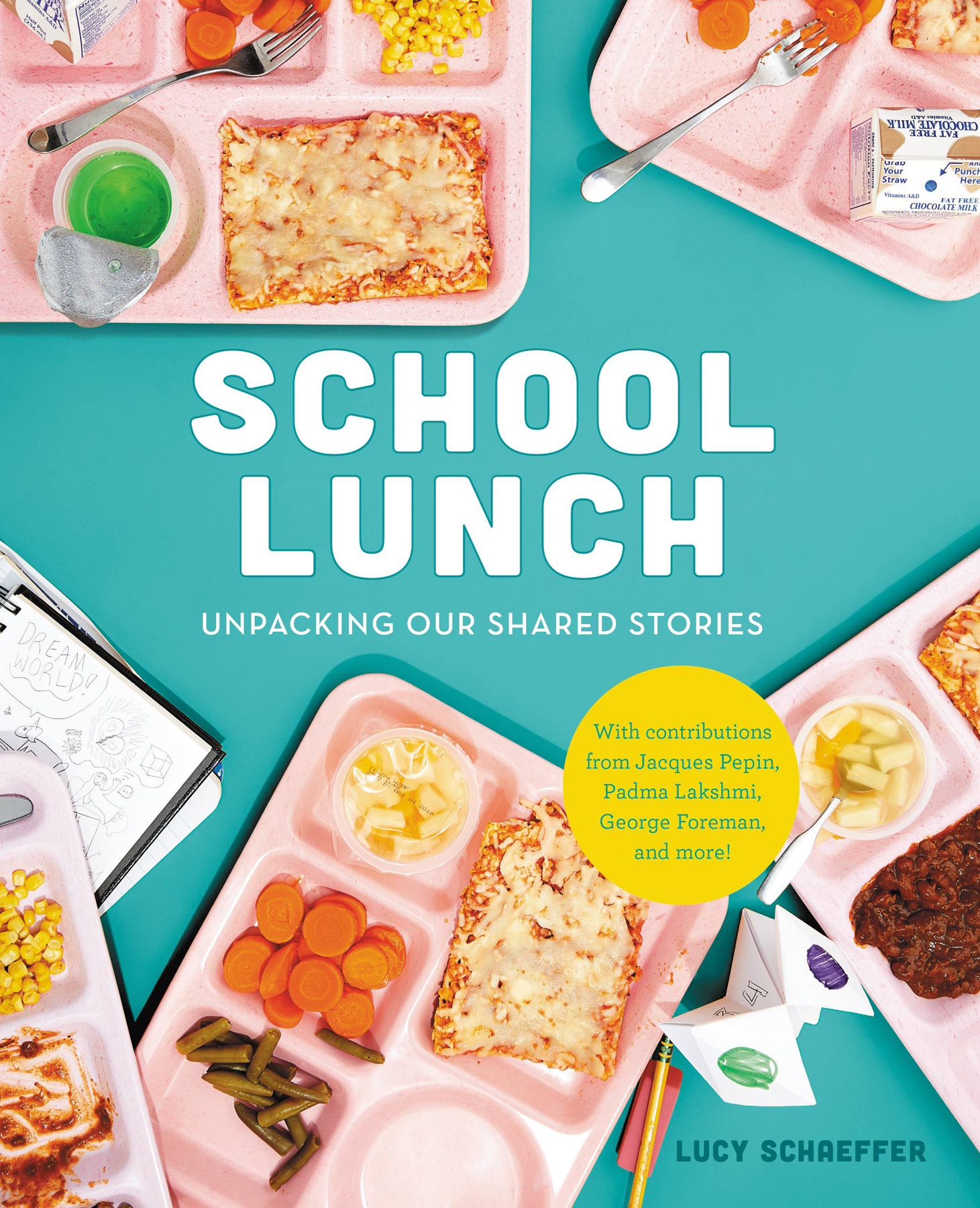

Copyright 2020 by Lucy Schaeffer

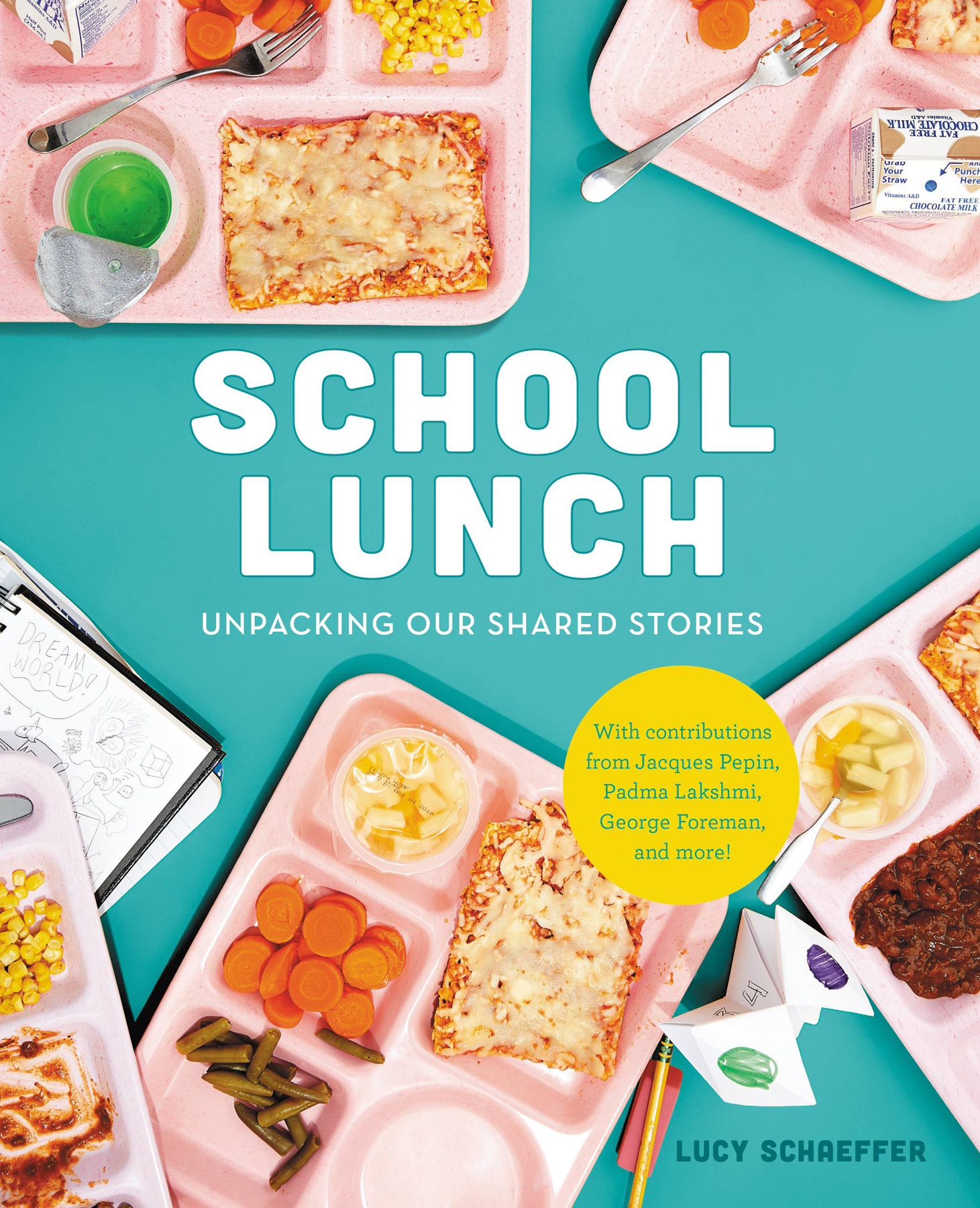

Interior and cover photographs copyright 2020 by Lucy Schaeffer

Cover copyright 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Running Press

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.runningpress.com

@Running_Press

First Edition: June 2020

Published by Running Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Running Press name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Food Styling by Chris Barsch

Prop Styling by Martha Bernabe

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019956737

ISBNs: 978-0-7624-9445-3 (hardcover), 978-0-7624-9444-6 (ebook)

RRD-Shenzhen

E3-20200414-JV-NF-ORI

For Georgia and Annie,

my beautiful daughters who forgive me when I accidentally switch their lunch bags.

MY PARENTS ONCE JOKED ABOUT PACKING A DEAD MOUSE IN MY little brothers school lunch. The fall Mikey started first grade, the field mice were growing bold and trying to colonize the warmer nooks and crannies of our cupboards. Traps were snapping daily. Simultaneously, at school, my brothers entire bag lunch was being swiped from his backpack before lunch period. My parents reasoned a dead mouse sandwich might scare a young thief straight. Ultimately, a simpler solution prevailed. My moma wonderful cook and baker for my whole childhoodhad been making homemade bread and cookies for Mikeys lunches, with him helping at her side. She decided to lower the bar. She swapped their homemade bread for store-bought and skipped the cookies. The lunch bag thievery halted immediately. Seems some little kid had just been unable to resist the temptation of her home cooking.

While I must have had some of that homemade bread myself, for the most part my own elementary school lunch was standard fare: peanut butter and jelly, corn chips (which I liked to stick in my sandwich for added crunch), carrot sticks, a box of Juicy Juice, and a packaged Little Debbie treatall tucked neatly in my metal Pigs in Space lunch box. While this seemed absolutely average and unremarkable at the time, I can look back on it now as having an indelible time and culture stamp, one that every school lunch bears.

Ive come to realize that school lunch is the perfect lens through which to consider what it means to be American. When I first started this project, I had no idea the depth and breadth of experiences I would discover. Ive collected stories from people aged six to ninety-three; hailing from twenty-five different countries and all across the United States. My subjects include celebrities, homeless people, strangers, my parents, our corner bodega owner, and my Korean father-in-law. Each story highlights our diversity while revealing our common experiences and our shared humanity. No matter where everyone came from or how divergent their childhood circumstances were, we are all Americans now. Our diversity is our strength. Now more than ever, this feels important to me to celebrate.

The lunches in this book are focused on the elementary school years. With all the mythology around the carefree innocence of childhood, its easy to forget that at that age, you dont have much control. For lunch, you get what the adults around you decide you should eat or are able to providewhether you like it or not. Micaela Walker recalls getting the exact same lunch every day for six years. She begged her mother to change just the direction she cut the sandwich, but with no luck. Many kids remember cafeteria trays with overcooked, ignored veggies and mystery meat. Thats life as a kid.

Of course, not all family circumstances are equal. George Foreman remembers blowing up an empty paper bag and bringing it to school on the days when there wasnt food at home. Many countries seem to do a better job than ours at providing healthy, free school meal options for kids. Hearing some of those international cafeteria stories was eye opening. Id happily eat Marcus Samuelssons Swedish school lunch of pancakes with fried ham and lingonberry jam every day for six years.

Its remarkable how vividly adults remember visceral details of their childhood lunches, and how those lunches made them feel. Annegrete Barnum, who was eighty-eight when we spoke, recalled her childhood school lunches during World War II and in Allied-occupied Germany. She eagerly described brown bread, spread with lard and sprinkled with sugar, as clearly as if she had just eaten it that morning.

Padma Lakshmi recalled the shame of being different when she took out her pungent Indian lunch in front of American classmates. She still remembers feeling conflicted. The taunts stung, but she preferred her lunch to their bland white-bread sandwiches and thus didnt actually want to trade. Diep Tran, transported to a Los Angeles suburb from Vietnam as a refugee, remembers being delighted and fascinated when she first encountered fanciful American dishes such as corn dogs, a dish whose name reveals little about its contents.

People recalled with equal clarity items they didnt get in their lunches. Items that other, luckier kids lorded over them. Deals, trades, and pleas for those coveted commodities seem to be a universal experience that crosses cultural boundaries. Benevolent classmates who shared such luxuries are remembered fondly by first and last names decades later. Ive asked hundreds of people about their school lunches and can conclude most of us remember other kids as being the ones who got the really good stuff.

Familial idiosyncrasies play just as large a role as culture in determining school lunch. One mom, dad, or grandparent can sway what is expected, by doing things their own way.

Aya Ogawas Japanese mother brought personal ingenuity to the lunches she packed. The family had lived in Atlanta, Georgia, for a few years before Aya started kindergarten in Tokyolong enough for her to acquire a strong taste for American baloney. Back in Tokyo, Ayas mother synthesized the two cultures and tastes. She packed baloney sandwiches on white bread with crusts trimmed and then cut into six rectangles, spelling the kanji characters of their family name, Ogawa ( ).

).

A completely different maternal adaptation story comes from Josephine Mangual. Growing up in Spanish Harlem in the 1960s, she and her Puerto Rican friends chatted and laughed but ate nothing during lunch period in the cafeteria. Their real lunch came at recess, when their mothers gathered daily with tins of hot food that they passed through the playground fence. It was a social gathering for the women as much as sustenance for the children. They always brought extra for all the additional kids who flocked over hoping for a taste of fried plantains or

).

).