Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Names: Sanneh, Kelefa, author.

Title: Major labels : a history of popular music in seven genres / Kelefa Sanneh.

Description: New York : Penguin Press, 2021. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021008355 (print) | LCCN 2021008356 (ebook) | ISBN 9780525559597 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780525559603 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Popular musicHistory and criticism.

Classification: LCC ML3470 .S25 2021 (print) | LCC ML3470 (ebook) | DDC 781.64dc23

INTRODUCTION

Wearing Headphones

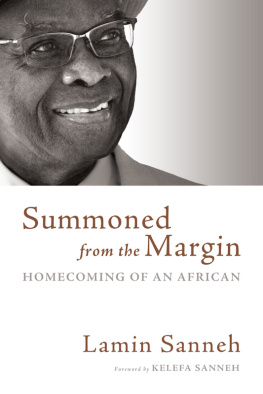

W hen my father was lying in a hospital bed in New Haven, Connecticut, struck down by a sudden illness, and the doctors and nurses were searching for any sign that he was still alive, my mother decided that he needed a soundtrack. She brought his Bose noise-canceling headphones to the bed and we took turns playing him his favorite music. Over the next week, as we kept him company and said goodbye, one of the albums we put into heavy rotation was Clychau Dibon, a shimmering collaboration from 2013 between Catrin Finch, a Welsh harpist, and Seckou Keita, a kora player from the Casamance region of Senegal, in West Africanot far from where my father had grown up, in the Gambia.

The kora, a harp-like device with twenty-one strings held taut between a wooden neck and a calabash body, was my fathers favorite instrumentno doubt it reminded him of the village life he left behind when he was a teenager. He named me after a legendary warrior who is the subject of two of the most important compositions in the kora tradition, Kuruntu Kelefa and Kelefaba. And I once spent a surreal summer in the Gambia as a kora student, taking long daily lessons from a teacher with whom I communicated mainly in improvised sign language. I remember how excited my dad had been when he discovered that harp-and-kora album, a warm and atmospheric hybrid that sounded instantly familiar to him. Sometimes when people talk about loving music, this is what they mean. You hear something that resonates with some fragment of your biography, and you feel you wouldnt mind if those were the last sounds you ever heard.

Often, though, falling in love with music is a more complicated and contentious process. When I was growing up, I thought of my dads beloved kora cassettes as finger-chopping music, because of the keening voices of the griots, who sounded to me as if they were howling. I had no interest in it, just as I had no interest in classical composers who were often heard in my house, and whose creations I learned to play on the violin, starting when I was five. Like most kids, I liked the idea that music could carry me out of my house and into the streets, into the city, and beyond. I started by asking my mother to buy me a cassette of Michael Jacksons Thriller, because everyone at school was talking about it. And soon I moved on to early hip-hop, old and new rock n roll, and eventually punk rock, which transformed my moderate interest in music into an immoderate passion. Punk taught me that music didnt have to express consensus; you didnt have to sing along with whatever was coming from the family stereo, or whatever you saw on television, or whatever the kids at school were into. You could use music as a way to set yourself apart from the world, or at least some of the world. You could find something to love and somethingperhaps lots of somethingsto reject. You could have an opinion, and an identity.

Does that sound obnoxious? Probably it does, and probably it would have sounded even more obnoxious if you had asked me to explain it when I was a teenager, newly converted to the gospel of punk. But I think that musical fandom tends to be at least a little bit obnoxious or embarrassing, which is why its so easy to make fun of obsessive listeners, whether they are pretentious music snobs or wide-eyed pop stargazers, owlish record collectors in basements or aggressive stans on social media. (The term stan comes from a track by Eminem about a fan who is morbidly and romantically fixated on him; both the track and the term reflect a widespread belief that there is something shameful and scary and unmanly about fans hunger for their idols.) We can, for the sake of politeness, agree to disagree and not to mock one anothers musical tastes. But even those of us who are nominally grown-ups may find that we never quite outgrow the sense that there is something profoundly good about the music we like, something profoundly bad about the music we dont, and something profoundly wrong with everyone who doesnt agree. We take music personally, partly because we learn it by heart; songs, more than movies or books, are designed to be experienced over and over, made to be memorized. We take it personally, too, because we often listen to it socially: with other people, or at least while thinking of other people. Especially in the late twentieth century, American popular music grew increasingly tribal, with different styles linked to different ways of dressing, different ways of seeing the world. By the 1970s, different genres had come to stand for different cultures; by the 1990s, there were subgenres and sub-subgenres, all with their own assumptions and expectations.

In some ways, this is a familiar story. Many people have a vague idea that in the old days, popular music was popular, and that somehow popular music got increasingly fragmented and obscure. We put on our headphones and escape from the world into our own curated soundtracks. But at the same time, many fans have kept faith with the idea that music brings people together, assembling audiences that cross boundaries. The truth, of course, is that both of these ideas are important and true. Popular songs or styles or performers can erase boundaries, but they can also erect new ones. The early hip-hop records, for instance, sparked a movement that drew fans from all over the planet. But that movement also helped sharpen a generational divide, giving young Black listeners a way to renounce the R&B that their parents loved. And in the 1990s, country music became more suburban and more accessible. But it nevertheless remained a world apart from the pop mainstream. (Country music gained new listeners, in fact, by portraying itself as a gentler, more tuneful alternative to the increasingly truculent sounds of nineties rock and hip-hop.) Often, the economics of the music industry helped reinforce these divisions. Radio stations encouraged listeners to think of themselves as partisans, loyal to their favorite stations. Record stores arranged their wares by genre, hoping both to enable efficient shopping and to inspire serendipitous discoveries. And record companies scrambled to identify audiences and trends, searching for ways to make the listening public a little less unpredictable.