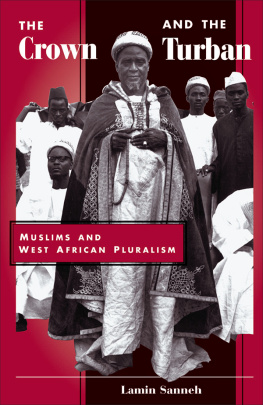

First published 1997 by Westview Press

Published 2018 by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names maybe trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sanneh, Lamin O.

The crown and the turban : Muslims and West African pluralism /

Lamin Sanneh.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8133-3058-0 ISBN 0-8133-3059-9 (pbk.)

1. IslamAfrica, West. I. Title.

BP64.A4W367 1997

297,.0966dc20 96-35598

CIP

ISBN 13: 978-0-8133-3059-4 (pbk)

To Sand, K, and Sia

True happiness consists not in the multitude of friends,

But in the worth and choice.

Ben Jonson (d. 1637)

The rapid changes of recent years have forced us sometimes painfully to realize that the world is a much more diverse place than we had previously thought. As well as other countries and nations, there are also other cultures and civilizations, separated from us by differences far greater than those of nationality or even of language. In the modern world, we may find ourselves obliged to deal with societies professing different religions, nurtured on different scriptures and classics, formed by different experiences and cherishing different aspirations. Not a few of our troubles at the present time spring from a failure to recognize or even see these differences, an inability to achieve some understanding of the ways of what were once remote and alien societies. They are now no longer remote, and they should not be alien.

Bernard Lewis

Some of the material assembled here had appeared in earlier forms in scattered places. I have hunted and gathered it into what I trust is a permanent home and in so doing reworked and supplemented it within an integrated framework. In doing so, I discovered that the task to reconstruct amounted to a separate, entirely new enterprise going beyond mere rewriting and rectifying of details. For example, the essay style allows for the staged development of an idea or theme characterized by closure and final integration. However, such a style would be inappropriate for chapters in a book, for then the chapters would become stray pieces in want of anchorage, with the whole being less than the sum of its parts. As it happens, one major focal point that emerged in the course of recasting the material is the ideas of Ibn Khaldun, which are transfused throughout this book.

Thus it may be said that the demand to produce a work dealing with the social, political, and intercultural dimensions of Muslim Africa has provided the motivation for a fresh synthesis, reconstruction, analysis, and reflection, and I took advantage of that reassessment to introduce new materials and to readjust everything else. For that opportunity I am grateful to the Pew Charitable Trusts for a grant to undertake an assessment of current needs and concerns in Muslim and Christian Africa. I am also indebted to colleagues and friends in Procmura in Africa, whose dedication to interreligious issues has encouraged and guided the inquiry represented in this book. I owe a huge debt of gratitude to a long line of teachers, mentors, supporters, colleagues, students, and friends who inspired and guided me to embark on the study of Muslim society, first in the Middle East and then in West Africa; people such as John Crossley, John Taylor, Henry Ferguson, Ted Lockwood, Hans Haafkens, J. Spencer Trimingham, Tom Beetham, Thomas Hodgkin, Hugh Thomas, Johann Bauman, Kenneth Cragg, John Taylor, Humphrey J. Fisher, Patrick Ryan, Trine Paludan, Andrew Walls, Richard Gray, John Carman, Wilfred Smith, Bill Burrows, Jim Tally, and in Africa the numerous individuals, men and women, Muslim and Christian, who over the years steadied my hand when I was new to or uncertain about the subject, and who, equally invaluably, deepened and corrected my understanding. I owe them all more than words can express. A draft of the book was first developed as the Henry Martyn Lectures at Cambridge University, England, and I am grateful to the Trustees of the Henry Martyn Trust and to David Ford and Graham Kings and their colleagues for the invitation. But it goes without saying that I alone take responsibility for the views expressed here.

I am aware of numerous people who have helped me in this work and in other ways clarified my ideas and understanding of the subject. But most of all, I pause to acknowledge the help of my family. I shudder to think of the many sins of omission and commission that are mine in any case but am further disturbed by the time and resources taken away from family responsibility in order to write this book. I am encouraged by the reminder that this book will always stand in relation to my family like the perishable before the imperishable, for what is even a clamorous literary distraction compared to loves tranquil scope? May I, nevertheless, offer this book as a token of appreciation, however inadequate as evidence of my deep indebtedness to them, and gratefully acknowledge that I simply could not have done it without their much abused forbearance.

I may, perhaps, be indulged in the hope that this work will revive interest in what was once a growing field of academic inquiry, namely, the historical exploration of religion in its social, political, and intellectual dimensions, and do so in the context of the pluralism of contemporary society. I have tried to deal with this pluralism in two fundamental ways: first, in terms of continuities and parallels, and, second, in terms of contrasts and divergences. In the first case I have shown the responses and convergences between Islam and indigenous African traditions, and in the second, I have indicated where the Muslim demand for Islam to be buttressed by the state conflicts with modern Christian and secular beliefs. However, even in the case of Muslim political militancy there are areas of potential fruitful convergence, so that the Muslim insistence on the relevance of religion to political life may be reconciled with that form of political liberalism that is hospitable to religious freedom. I have, therefore, been profoundly affected by the argument of the advocates of temporal Islam that religion without political relevance is worthless, and this understanding has led me to the view that, given the claims of Islam for divine providence in history, it would be a fatal compromise of those claims to entrust the religion to state supervision and vice versa. Religion may be too important for the state to ignore, but it is too much so for the state to enjoin it. Similarly, the state is too central to human interests for it not to overlap with the religious domain, but it is too contingent for it to behave as revealed truth. On both counts, that is to say, on the grounds of religious interest and of political contingency, we are left with a version of separation of church and state and thus with the fruitful convergence between religious voluntarism and political liberalism. In any case, that is the view put forward in this book. Thus the theme of continuities and parallels pervades the general outlook of this book and has influenced its conclusions.