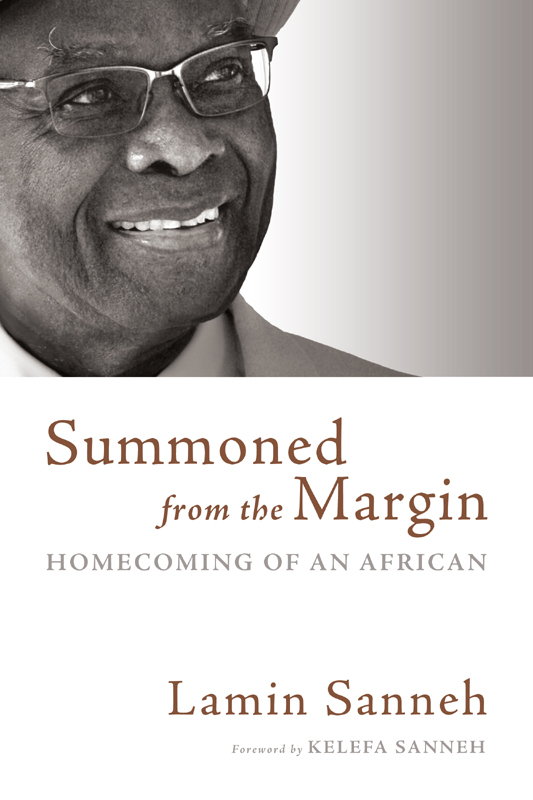

For most of the four decades I have known Lamin Sanneh, I have urged him to write a memoir of his personal pilgrimage. At last my prayer has been answered! I treasure this marvelous addition to the history of Christian and African autobiography that reaches back to Saint Augustine.

PATRICK J. RYAN

Fordham University

Lamin Sannehs autobiography is moving, humble, and very thought-provoking. A convert to Christianity from Islam and now a leading missiologist at Yale, Sanneh speaks simply from a rich and sensitive Christian faith.... He has the rare quality of a top academic as well as a humane and spiritually discerning communicator.

GAVIN DCOSTA

University of Bristol

This moving narrative vividly portrays the many stages of Lamin Sannehs religious journey, connecting his personal experiences on four continents with major cultural shifts in the last fifty years.... Sanneh offers a sobering critique of Western Protestantism and explains his confidence in the progress of African Christianity, expressed in the mother tongue. His painful memories of multiple rejections should sharpen our reflection on our Christian past and present.

JOHN B. CARMAN

Harvard Divinity School

All this goes on inside me, in the vast cloisters of my memory. In it are the sky, the earth, and the sea, ready at my summons, together with everything that I have ever perceived in them.... In it I meet myself as well. I remember myself and what I have done, when and where I did it, and the state of my mind at the time. In my memory, too, are all the events that I remember, whether they are things that have happened to me or things that I have heard from others. From the same source [of memory] I can picture to myself all kinds of different images based either upon my own experience or upon what I find credible because it tallies with my own experience.... The power of the memory is great... it is awe-inspiring in its profound and incalculable complexity. Yet it is my mind; it is myself. What, then, am I, my God? What is my nature?

ST. AUGUSTINE

Summoned from the Margin

HOMECOMING OF AN AFRICAN

Lamin Sanneh

William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company

Grand Rapids, Michigan / Cambridge, U.K.

2012 Lamin Sanneh

All rights reserved

Published 2012 by

Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

2140 Oak Industrial Drive N.E., Grand Rapids, Michigan 49505 /

P.O. Box 163, Cambridge CB3 9PU U.K.

17 16 15 14 13 12 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sanneh, Lamin O.

Summoned from the margin: homecoming of an African / Lamin Sanneh.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN 978-0-8028-6742-1 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4674-3675-5 (epub)

1. Sanneh, Lamin O. 2. Christian converts from Islam Biography. I. Title.

BV4935.S34A3 2012

270.82092 dc23

[B]

2012018930

www.eerdmans.com

To K and Sia Manta:

I have tried; you will do better.

Of that I cannot be more certain.

Its my greatest consolation.

Contents

I f my father had grown up in more comfortable, less precarious circumstances in a hardscrabble American small town, say, raised in a harried but happy working-class family then perhaps he would have been able to use the run-of-the-mill deprivations of his boyhood as an effectual rhetorical tool. My sister and I might have nodded (or, more likely, sighed) while he told us about the chores he had had to do, the vacations he had foregone, or the months and years it had taken him to save up for the bicycle he wanted. We might have been urged to compare our charmed lives to his, and to reflect upon our good fortune.

Instead we learned, in stray sentences and anecdotes, about a childhood that was entirely incomparable to our own. Dad came from a country that none of our friends had ever heard of: Zambia, they usually thought we said, and some couldnt believe there was another African country, even more obscure, with almost the same name. No, we told them: Gambia. His mother was a member of a small, complicated team of wives a social arrangement that sounded, to a pretty-much American boy and his all-American friends, like a dirty joke come to life. Even my fathers journey, as a teenager, from a tiny town on a tiny island to the biggest city in one of the smallest countries on earth, seemed to belong more to myth than to the world of station wagons and trolley buses that I knew. He made his way, somehow, to Europe and to America, then back to Europe, back to Africa, and then, finally, to Scotland (where my memories begin), and then to America for good, it turned out.

I always wanted him to put his life into a book, not least because I wanted to read it. This is, as my father puts it, the story of his unlikely beginnings, although of course they only seem unlikely in retrospect, because of his stubborn and in some ways mysterious determination to live a life radically different from the one that his circumstances predicted. I have heard a few of these stories before, often at the table after dinner, as dessert (apple pie and vanilla ice cream, ideally) arrived and, nearly as quickly, disappeared. My sister and my mother and I would try to keep up as my father explained why he and his friends feared hippopotamuses more than crocodiles, or how his impoverished undergraduate years permanently ruined his appetite for Dunkin Donuts. But most of these stories are new to me, and, taken together, they capture clearly and movingly something I had only dimly perceived: the curiosity and restlessness that propelled my father out of the Gambia, and have propelled him ever since.

This book is also, perhaps mainly, a conversion narrative, though not a straightforward one. It felt like being awakened, my father writes about his growing awareness of the faith that has shaped his life and career. But he soon realized that waking up was hard work: The consternation that met me on my way to joining the church was a measure of the symbolic distance I had to travel from the Axis Mundi of my Muslim culture and history to the Christian faith which turned out to have its own margins to offer. In Banjul, Gambias capital, he found churches staffed by expatriates who felt uneasy about converting a local boy. Maybe they didnt realize that my father was already, in a sense, converted; in Banjul, he was merely searching for a community of believers who lived up to the faith that had already captured him. He had no way of knowing, then, how long that search would be, or where it would lead him. He had no way of knowing, either, that as Christianity became ever more truly a world religion, it would be at the so-called margin where the faith would thrive.