There are many people whom I must thank for their contribution to this book, foremost among them being the owners of many country houses I have visited over the years during a long association with Country Life . My colleagues in the architectural department of that magazine have been an unending source of erudition and delight. Today the flag is kept flying by John Goodall, with whom I have travelled Britain, entranced by his incomparable expertise in old buildings. John has been generous enough to read the manuscript, as did Tim Brittain-Catlin and Simon Thurley: their comments have been pure gold. Others who have shared abundantly of their knowledge are Mary Miers, James Stourton and James Knox. Any error is mine.

My first book, The Last Country Houses , was published by Yale in 1982; in 1990, the same press brought out The American Country House . After something of a break, I am delighted to find myself again racing under Yale colours. I would like to thank Heather McCallum and Sophie Neve for making this possible. Henry Howard has been the copy editor of my dreams.

My wife Naomi and sons William, Johnny and Charlie have tolerated my architectural obsessions over the years and William has come to share some of them, while outshining his father, by studying for a PhD on James Gibbs. Deepest love and thanks to them all.

Introduction

Eric Ponsonby, 10th Earl of Bessborough loved Stansted Park. This was something of a surprise to his friends, since the house, near Chichester, was rebuilt after a fire in the Edwardian period and, in the early 1980s, Edwardian architecture was regarded with scorn. I disagreed; Yale University Press had just published my book The Last Country Houses , a study of country houses from 1890 to 1939 . Which was why he asked me, as an eager young architectural historian, to help him revise his book about it, A Place in the Forest . Erics partiality sometimes got the better of him, yet how nice it would be to believe, as he did, that Roman legionaries really had once tramped down the long avenue.

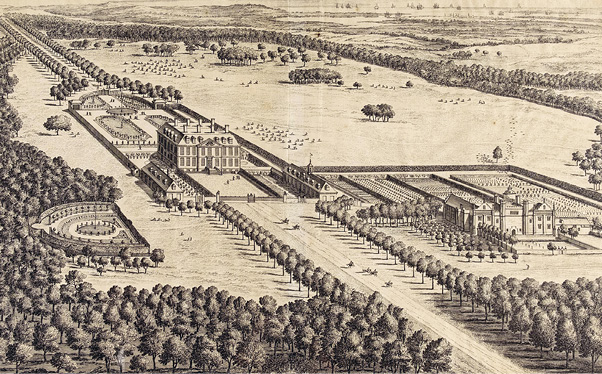

Outwardly Stansted may have been Edwardian but, like many country houses, it was more than that. For at least eight-hundred years, the people who owned it a colourful crowd, rarely related to each other, since they were singularly bad at producing heirs had been nurturing, reimagining and loving it perhaps as much as Eric did. Standing in immemorial forest, the first Stansted was used by Henry II as a hunting lodge in the late twelfth century. In 1480, the 12th Earl of Arundel replaced the lodge with a sprawling mansion in the ultra-fashionable material of brick. This building suffered a small bombardment during the Civil War and subsequently decayed so that all that now survives from Lord Arundels time is a fragment of rose-coloured brick on the outside of the chapel. In the 1680s, a new Stansted arose on a different site nearby, with a hipped roof, dormers and pediment, for the 1st Earl of Scarbrough, a favourite of Charles II and one of the statesmen who invited William III to the throne (fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Stansted Park, near Chichester: a country house that, like others, has undergone many transformations since it was first built in the Middle Ages. In the right foreground is a fragment of a Tudor house, later turned into a chapel. This aerial view of 1708 drawn by Jan Kip shows the house built by the 1st Earl of Scarbrough in the 1680s; much altered, it burnt down in 1900 and was replaced.

The following century saw the levelling of the formal gardens to make a landscape park, the construction of a triangular tower by the 2nd Earl of Halifax in 1772 and the arrival of yet another owner, the East India Company merchant and MP Richard Barwell, who made it his study to render himself obnoxious to persons of all ranks, according to a diarist, by shutting up the park; Barwell also remodelled the house. On Barwells death in 1804, Stansted was bought by Lewis Way, who would have become a clergyman if his father had not made him study law. After working for a wealthy but unrelated client who shared his surname, Lewis Way found he had been left 30,000. A member of the London Society for Promoting Christianity Among the Jews, Way transformed Stansted into a college where young, impecunious Jews could stay, be shaved and baptised, and train as missionaries to be sent to their own people. A donkey-riding school prepared them for travel in distant lands. It was Way who made the chapel out of surviving fragment of the Tudor house. During the three-hour service of consecration, the poet John Keats had ample time to study the stained glass in the north windows, where the arms of the Earls of Arundel inspired a stanza of The Eve of St Agnes .

In 1840, the exuberant Thomas Hopper built a stone conservatory for the new owner, a port wine merchant called Charles Dixon who founded an almshouse for six of his less successful brethren. Then, on the last day of the 1900 Goodwood Races, Stansted caught fire, in a blaze that lit up the country for miles around. Carvings by Grinling Gibbons, Italian ceiling paintings, pictures of the queens who were supposed to have slept there: all were destroyed. Stansted was rebuilt in an unexciting neo-Georgian style. This was the house bought by the 9th Earl of Bessborough in 1924, after Bessborough House in Ireland was burnt during the Troubles (fortunately, its contents had already been removed and some of its beautiful eighteenth-century pictures still hang at Stansted today). Bessborough asked his old Cambridge friend, the architect Harry Goodhart-Rendel, to come down in his Rolls-Royce and bring his new home up to date. The Sainte-Chapelle in Paris inspired a blue chapel ceiling, spangled with stars, and Rinaldo, as the architect was known, built a theatre modelled on the Duchess Theatre in London, which fired the young Eric with a passion for acting. In 1942 while watching a training film, a member of the Home Guard dropped a cigarette and the theatre went up in flames.

This book is an introduction to the history of places like Stansted. Stansted itself illustrates one of the difficulties of the subject: it went through so many iterations. Even country houses that strongly evoke a single period are often palimpsests where one era overwrites another, a process that may happen again and again until the deep past is no more than a ghostly, indecipherable smudge. The same place wears different guises. There is continuity in the place and idea of the country house, but the Stansted of today is nothing like the original hunting lodge. However, the long history of country houses like Stansted is a considerable part of their fascination. They are a document on which is written their owners changing lives, tastes and sources of income. Generally I shall touch on only one aspect of the houses I discuss but many, like Stansted, were altered in almost every generation.

All of which prompts the question: what is a country house? That is not so easy to answer. The meaning changes depending on the historical period being discussed. Like castle, the single word we have in English to represent numerous, more specialised terms in medieval Latin texts, country house is a catch-all. Chatsworth, in all its princely splendour, is a country house, but so is handcrafted Munstead Wood. Mighty Alnwick Castle, in the wilds of Northumberland yes, thats undoubtedly a country house. Politely Georgian Kenwood House, on the edge of Hampstead Heath most people would call that one too.