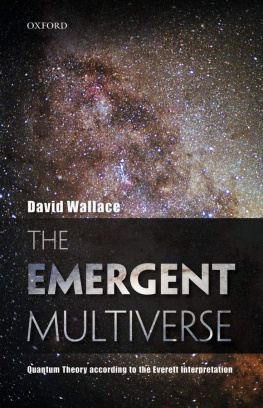

The Emergent Multiverse

The Emergent Multiverse presents a striking new account of the many worlds approach to quantum theory. The point of science, it is generally accepted, is to tell us how the world works and what it is like. But quantum theory seems to fail to do this: taken literally as a theory of the world, it seems to make crazy claims: particles are in two places at once; cats are alive and dead at the same time. So physicists and philosophers have often been led either to give up on the idea that quantum theory describes reality, or to modify or augment the theory.

The Everett interpretation of quantum mechanics takes the apparent craziness seriously, and asks, what would it be like if particles really were in two places at once, if cats really were alive and dead at the same time? The answer, it turns out, is that if the world were like thatif it were as quantum theory claimsit would be a world that, at the macroscopic level, was constantly branching into copieshence the more sensationalist name for the Everett interpretation, the many worlds theory. But really, the interpretation is not sensationalist at all: it simply takes quantum theory seriously, literally, as a description of the world. Once dismissed as absurd, it is now accepted by many physicists as the best way to make coherent sense of quantum theory.

David Wallace offers a clear and up-to-date survey of work on the Everett interpretation in physics and in philosophy of science, and at the same time provides a self-contained and thoroughly modern account of itan account which is accessible to readers who have previously studied quantum theory at undergraduate level, and which will shape the future direction of research by leading experts in the field.

David Wallace is Tutorial Fellow in Philosophy of Science at Balliol College, Oxford.

The Emergent

Multiverse

Quantum Theory according to the

Everett Interpretation

David Wallace

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP,

United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

David Wallace 2012

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2012

First published in paperback 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Data available

ISBN 9780199546961 (Hbk.)

ISBN 9780198705747 (Pbk.)

To Hannah

We have, then, a theory which is objectively causal and continuous, while at the same time subjectively probabilistic and discontinuous. It can lay claim to a certain completeness, since it applies to all systems, of whatever size, and is still capable of explaining the appearence of the macroscopic world. The price, however, is the abandonment of the concept of the uniqueness of the observer, with its somewhat disconcerting philosophical implications.

(Hugh Everett III, draft Ph.D. thesis; cut from submitted version at J. A. Wheelers request)

What would it have looked like if it had looked like the Earth went round the Sun?

(Attributed to Ludwig Wittgenstein)

Contents

Figures

Structure of the book

An object not among the basic posits of the Standard Model

Classical inference

Dutch book arguments

Decision-theoretic justification of personal probability and Bayesian updating

Deriving the Savage axioms in a diachronic framework

The Diachronic Representation Theorem

Objective probability in nonbranching physics

Justifying classical inference

Minimal approach to quantum probability

Quantum probability according to Saunders

Quantum probability according to Deutsch

Quantum probability according to Wallace

Quantum probability according to Greaves, as formalized by Greaves and Myrvold

Quantum probability according to Greaves and Myrvold

The Everettian Inference theorem

The Everettian Epistemic theorem

Four views of branching and identity

Schematic representation of spacetime branching

Schematic representation of spacelike separated measurements

Concatenating two neutron-beam splitters

Interferometry with neutron-beam splitters

Schematic view of parallel quantum computation

Four particles traversing DeutschPolitzer spacetime

Two particles traversing spacetime with temporally extended wormhole

The general Deutsch model of time travel

Removal of entanglement by time travel

Boxes

Aphase-space POVM

Scattering of light particles of heavy ones

Atomless history spaces

A metaphor for indefinite branch number

The Everett interpretation and free will

Consistency of the axioms

The irrelevance of macrostates

Two defnitionsofhistory

Overlap vs divergent worlds

I have been working on the Everett interpretation for my whole career, and on this book for most of it, and in the process Ive been privileged to have the chance to discuss quantum theory and its philosophy with a great many colleagues and friends. The greatest thanks, by far, are due to Simon Saunders, both for the enormous influence of his own work and, even more importantly, for his tireless engagement with my work as teacher, colleague, and friend. Without his support, this would have been a far weaker piece of work, at best. As likely, it would not have existed at all.

Other than Simon, special thanks are due to Hilary Greaves (whose influence on, in particular, of the book was very considerable, over and above her own writings on the topic); to Jeremy Butterfield, Frank Artzenius and Jos Uffink, who patiently read through, and provided detailed and helpful feedback on, most of the manuscript; to David Albert and Wayne Myrvold for extensive and challenging engagement with Everettian ideas, and to Harvey Brown, Olly Pooley and Chris Timpson for a decade and a half of good company and good conversation on matters quantum-mechanical and beyond. But Im also grateful to the many other colleagues whove discussed the interpretation of quantum mechanics with me over the last decade: Guido Bacciagaluppi, David Baker, Katherine Brading, Jeff Bub, David Deutsch, Cian Dorr, Artur Ekert, Chris Fuchs, Shelly Goldstein, Brian Greene, Robin Hanson, Lucien Hardy, Adrian Kent, Eleanor Knox, James Ladyman, Barry Loewer, Tim Maudlin, John Norton, David Papineau, Huw Price, Richard Healey, Paul Tappenden, Antony Valentini, Lev Vaidman, Alastair Wilson, Wojciech Zurek, and others too many to mention.

Next page